Blog post by Claire Bale, Associate Director of Research at Parkinson's UK, originally published 18 September 2023 on medium.

Problems with memory and thinking are common in Parkinson’s. But both people with the condition and health professionals can find it hard to broach the subject.

In this blog we hear from researcher Dr Rimona Weil and artist Anne Marr about a creative collaborative project called Patterns of Perception that aimed to address this problem and led to the development of two new booklets — one for people with the condition and their families, one for health professionals — to help open up conversations about Parkinson’s dementia.

Let’s meet them!

Rimona: I’m a neurologist at the National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery, Queen Square. And I’m a neuroscientist at University College London. My research is focused on how dementia happens in Parkinson’s.

Anne: I’m a programme director at Central Saint Martins, part of University of the Arts London and my background is in textile design.

Rimona, where did the idea for the project come from?

The idea for the project came because of this problem I’ve experienced in my research and in my clinical practice. People just do not want to talk about dementia in Parkinson’s. And I include myself in that! I felt nervous to talk about it because I thought it would upset or worry patients.

But if we don’t talk about dementia people won’t get the right treatments and support, and we won’t be able to do the research to develop better treatments for the future.

So the idea of the project was to unpack this problem and explore whether we can find better ways to talk about this.

I had worked with Anne before, alongside another artist called Ruairiadh O’Connell, on a project exploring the experience of living with Parkinson’s. We found that using art and creativity really helped people open up, and stories came out that we weren’t expecting to hear. So it felt like a similar approach could help us explore this problem with people living with Parkinson’s.

Anne, can you tell us a bit more about your role at Central Saint Martins and how you see art contributing to projects like this one?

Working with communities to exchange and gain new knowledge is really where my interest lies. Can we work in a very creative, imaginative way to give people a safe space to open up and share their experiences? I have had three family members who have experienced dementia so I was particularly interested in this project because I know what it feels like as a family member of feeling unsure how to talk about this. And having worked with Rimona and her team before I knew that we were in the right hands to explore this topic.

Rimona, can you tell us what the project involved?

We developed the project with the public engagement team at UCL and we started with creative workshops to start exploring peoples’ perceptions of Parkinson’s dementia. We ran the workshops in two stages.

The first one was quite broad and focused on unravelling the general taboo about dementia, but the second one was more structured. We asked participants questions like: Where do you want to find out about dementia? Who do you want to hear it from and in what sort of format?

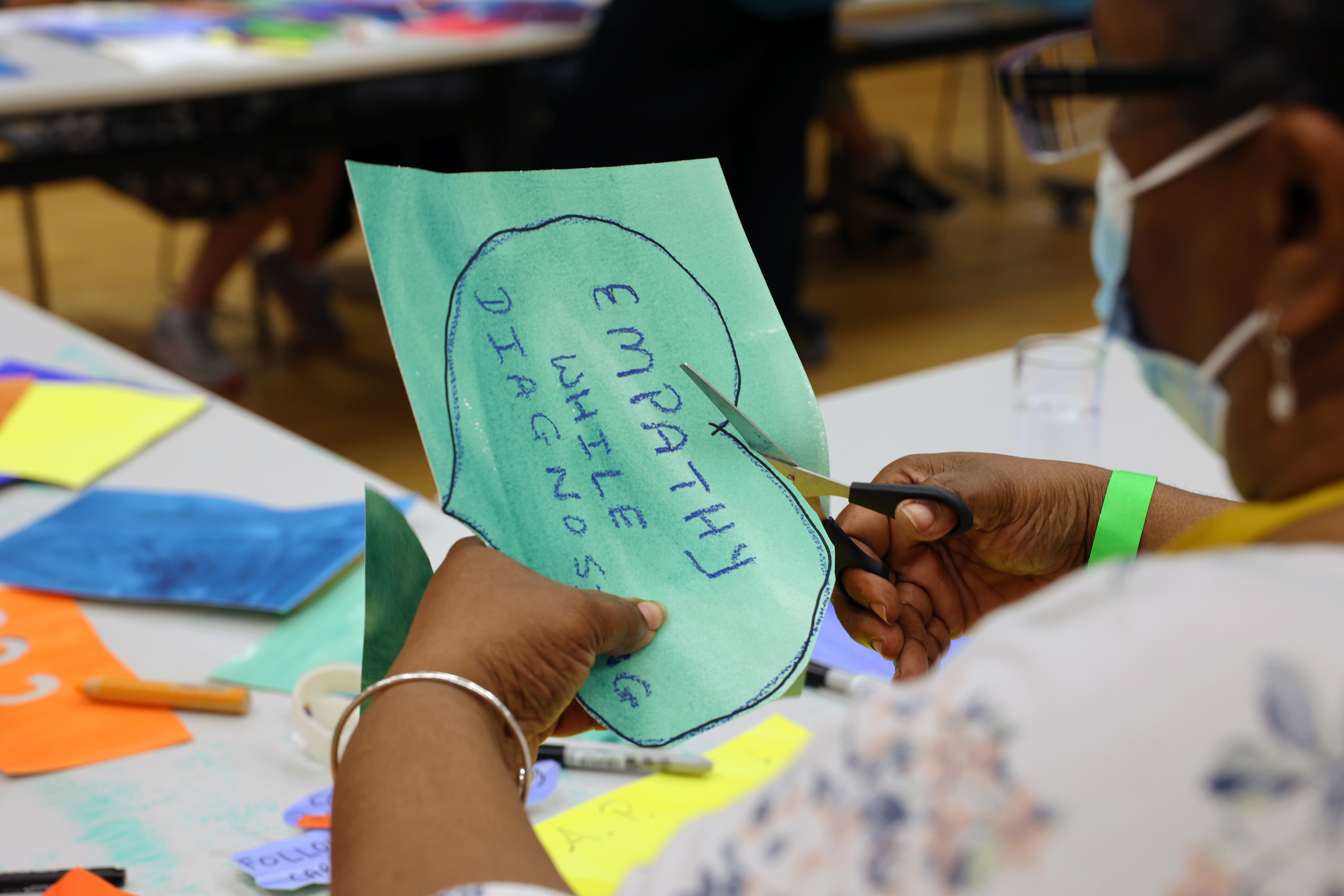

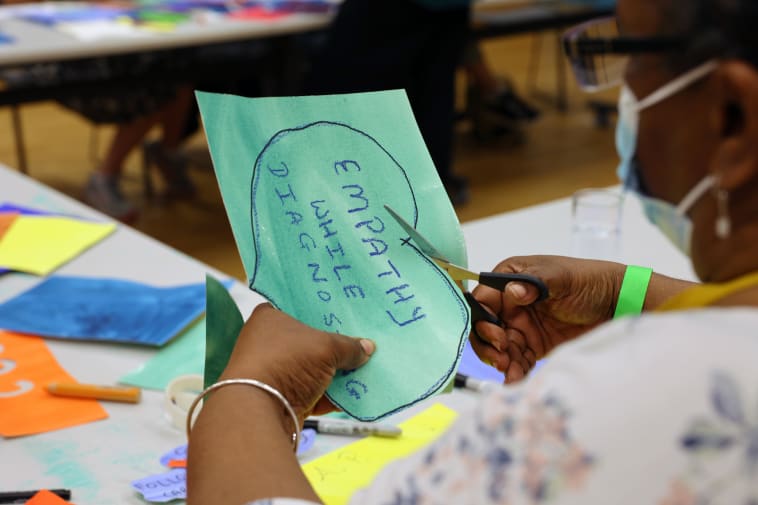

We got people to cut out and draw different elements to really bring their ideas to life. So at the end of the workshops we had the starting point for developing new resources about dementia.

We then created draft resources and used focus groups to refine them. We included people who had been involved in the original workshops in this process, and also new people and healthcare professionals, who had not been involved in the project to look at both booklets as well.

It was really important that we included as diverse a range of voices as possible — both in terms of people with lived experience, and in terms of professionals — to make the booklets relevant and accessible to as many people as possible.

Anne, can you tell us about the creative activities that you planned for the workshop?

At the beginning Ruairiadh O’Connell and I started out with lots of ideas which we discussed with the team and also with Janet, a volunteer with Parkinson’s who was involved in our previous project. That was super helpful, she really encouraged us to be direct and not too careful.

We wanted to make sure the activities we chose were inclusive. People sometimes think they need to be good at drawing to take part and can feel quite stifled by expectations to create ‘art’. So that’s why we always do a simple icebreaker activity. For this one, we gave people a piece of fabric and asked them to cut out their own emotional journey with the condition.

We also had a trained Pilates teacher come in and do a physical warm up with us, which really helped to set the tone and the mood for the session.

Finally, we had people available to help participants, say to draw or cut something so they felt like they could express themselves as much as possible.

Rimona, how does working on a project compare to your usual day-to-day clinical and research work? And has this project informed your wider work?

There was a sort of freedom to it. When you’re running a regular research project or you’re in the clinic, there isn’t the space to have these kinds of conversations.

It’s definitely given me the confidence to talk about dementia. I realise now that I was hiding away from it and listening to our participants and hearing peoples’ responses to our booklets have helped me feel more at ease starting these conversations.

The other thing that I’ve learned is how important it is to include a diversity of voices, especially underrepresented groups. We were lucky to work with Moïse Roche, a researcher who works with and is part of the Black African community. He made really important suggestions and helped us reach out to different groups.

I never collected ethnicity data before because I worried I’d ask the wrong questions and offend people but having Moïse involved meant we could check things. And I’ve learned that if you don’t reach out to under represented groups, you just won’t include everyone.

Anne:

This was also a really important consideration when we designed the creative activities, we were thinking about how to make them inclusive. For example, one of our early ideas was to have a gardening theme — but is that something that would feel relevant to everyone?

How did working with Parkinson’s UK add value to the project?

Rimona: We were delighted that Parkinson’s UK became a partner on the project. We didn’t dare to dream what it might mean and it turned out to be so powerful. We’ve massively benefited from your expertise in producing resources, and from the connections you have with the community and professionals. And the fact that the booklets are now part of the Parkinson’s UK’s suite of information resources and will be hosted and managed by the charity means they are going to reach, and hopefully benefit, so many more people.

Anne: Definitely, and this whole collaboration has felt fairly effortless. Sometimes collaborative projects can become quite complex and different people have different ideas or agendas which can make things difficult but I never felt like that with this project. I always felt we were all on the same page. Everyone was encouraged to chip in with their expertise but also kept an open mind. I really appreciated that way of working together.

Finally, what would you say to researchers who may feel inspired to try something like this?

Rimona: The funding for this project came from the Wellcome Trust through a ‘research enrichment’ grant — and it really has enriched my research. We simply cannot do dementia research if we cannot talk about dementia. So I would encourage other researchers to think along these sorts of lines because it’s been incredibly rewarding and I can see that it’s going to have a real impact. I’m particularly proud of the scale of the collaboration we achieved.

Anne: Yes, I think a lot of artists and designers would love to work more with health practitioners and researchers. It’s a really worthwhile experiment and experience. And I could see this leading to, further, long-term exploration and research as well.

Thinking and memory changes information on the Parkinson's UK website.

Order a printed copy of the thinking and memory changes in Parkinson’s booklet.

Download the toolkit for detecting and managing Parkinson’s dementia for healthcare professionals.