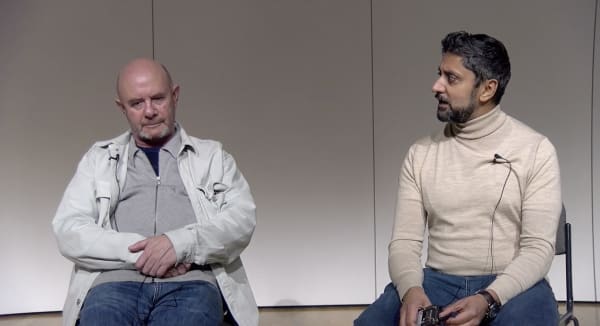

Nick Hornby in conversation with MA Performance: Writing Course Leader Ray Grewal

- Written byCat Cooper

- Published date 01 December 2023

At the Performance Programme's Extended Cinema Club

“Nick Hornby had to become a best-selling author before he could get one of his scripts made.” And with this humbling thought, MA Performance: Writing Course Leader Ray Grewal introduced Central Saint Martins’ students to the author of Fever Pitch and About A Boy, whose adaptations of An Education and Brooklyn won him Oscar nominations. His most recent book explores the parallels between two artistic geniuses centuries apart: Dickens and Prince.

On a previous visit to Central Saint Martins, Nick shared an early draft of the script for An Education with writing students. Before that, Nick had adapted Fever Pitch himself for the UK market in the nineties. He recalls the process, and how a pleasant time spent adapting the book developed into a reticence to do more screenwriting: “Fever Pitch was a very nice experience and sort of gentle, because I wasn’t expecting anything from the process at all. I wrote one or two drafts on spec with the Director, and then we sold it to Channel Four and Film Four and we just jumped through hoops until it got made.”

However, it was four years later that the film came out in 1997. Then High Fidelity, his next book, was in development. Nick explains that he didn’t want to spend two years writing a book and another four years adapting it, “taking out everything I had just put in”, and having lots of new ideas that he would rather work on than the old ones. “All the film and television work I’ve done since has either been adapting somebody else’s, or originals.”

There was a similarly long period in the making of An Education. It was a story that started life as a 7-page essay by journalist Lynne Barber published in literary magazine Granta. The film would go on to gain strong attention, and resulted in Oscar nominations for both Nick, his wife who was the producer and for the film itself. It took his screenwriting work to a whole new level. “It put me in a different field and suddenly I was being approached.”

Nick explains some of the changes to the story in drafting the screenplay. “When I adapted it, I didn’t know what it was about. I could make a story out of it, but I didn’t know what it was about in terms of its themes or what it was trying to say and so most of the drafts were homing in on what I thought was the meaning of it.” There was “a very hard shell to the piece” courtesy of Barber that Nick realised he had to work on, so that the character became “Lynne Barber aged seventeen, not Lynne Barber looking back at being age seventeen.”

Nick collaborated with Hollywood actress Reece Witherspoon on the film Wild after she had expressed a desire to work together in an initial meeting years before. He read a review of the book in The New York Times and while it sounded exciting, he was “very disappointed to see a pair of walking boots on the cover.” The dismay was forgotten on reading the book and when he discovered that Witherspoon owned the rights to the film, it presented the chance for them to work together.

Nick’s first three books were about men in their thirties, and he realised that he didn’t want to dramatise their problems anymore. He credits writing An Education for a new lease of life. “The revelation I had working on An Education was twofold: one was that young women, especially young women in times that are not the present, their problems are real. Their obstacles are real. Compared to my slacker thirty-somethings, whose only problems were in their head.”

And second? “If you can write an amazing part for women, you will get amazing actors”. Hornby recalls that when they were ready and going out to cast, it was clear that because of the centrality of the character they could get any young female actor they wanted. Women in their thirties who were “fed up getting the parts of the superhero’s girlfriend” as Hornby puts it. “There was no question, Carey Mulligan was the best of her age. She was desperate to do it. We created a star, and she got her Oscar nomination.”

A student in the audience asked: does Hornby somehow identify with his recent subject Charles Dickens, a fellow British writer known for his generational description of England? “I really identify in lots of ways with him. Tonally because he does the kind of funny/sad thing. I think he’s a really brilliant comic writer…But I think the most important lesson for me is that you have to be entertaining if you want to be read, and it's a very simple thing, but he was the great entertainer. And so was Shakespeare.”

If Dickens and Shakespeare were popularist and wrote for everybody, what is the process a writer goes through that then makes them revered and studied and enjoyed mainly by an ‘elite’, Ray Grewal wants to know? “Age. Once you become harder to read, there is that distance where you have to make a bit more of an effort.” Hornby also shares his views on getting your work picked up for screen. “I wrote a novel set inside a man’s head inside a record store. Just because it has a lot of dialogue doesn’t make it a movie. I don’t think you can predict what will be picked up for adaptation.”

In writing Dickens and Prince, Hornby discovered “that they are both anti-perfectionists.” That this hasn’t harmed their trajectories as artists or the regard for their work is something that Hornby identifies with. Their choices and personalities are also important to him. “I don’t mind letting my babies go. By the time they’re done, they’re done, and I’ve got another idea.”

“Through living in the world” is how Hornby can write narratives and characters outside of his own identity: “That idea of write about what you know is pretty broad – what you know is a certain type of life and a certain type of people. It’s all about observing.” Nick also talks about cultural appropriation and his rejection of arguments around not being able to write about other people: “I don’t think I would write a novel set in Africa about an African village. It would be crazy. I would be off with everything I did. But can I write about a young Black woman who lives in North London? I think I can. I have lived around those people for all of my life.”

Asked about his methods for writing screenplays, Nick jumps straight into the script. “I’ve tried to write synopses several times before and it’s a killer. I am a prose writer, and I can’t stand bad sentences. Treatments take me forever and I think, I might as well write a bloody draft.” He usually has an idea of what he wants to do before starting. “Sometimes to get the job, you have to have an idea of how it will adapt and be structured to pitch it.”

Hornby believes the best hope that something remains timeless is “to be entirely true to your time: it’s really about how true it is and how true to people it is. One thing about contemporary novels: they’re the best source of social history.” He feels that it’s not within our gift years later to decide that historic works are now problematic. “You want to see those attitudes for how they were. Because it offends people in the middle of the 21st century, I think my attitude is ‘read something else’. Let everything else rest. Of course, if it’s being taught to people there’s a debate to be had. But I would say ‘don’t teach it, let them discover it at a later time.”

Hornby’s advice for writers working in film and television is that you must be prepared to respond to events, to collaborate and to listen to what other people say. “No way anyone’s going to make your film if you say you won't change anything. Directors can say that, but not writers.”

He is unafraid to voice a discomfort around some of the measures being used in the industry to improve diversity on screen, if it means straying from the realities of the context or time period. “I think in terms of diversity, what we need is different stories. I think it’s an unhappy way of doing it to impose diversity on something that was not meant to be diverse. Write something new, do something different. What are you saying about history that makes everything seem easy in retrospect? That there was no racism, that there was no barrier to people?”

Grewal agrees: “It's the same thing as going back and rewriting Roald Dahl or Ian Fleming. If you’ve all read 1984, the main character, Winston Smith’s, job is to rewrite history after somebody has said something. So, if a government minister makes a mistake, you go back and rewrite what they said. So what people are doing is updating history to make it sound like there was no racism, there was no problem. Because they’re just rewriting the past. You’ve got to ask, who is pushing this, is it Black or Asian writers or filmmakers?”

Asked about his outlook for the industry and the role of the screenwriter: “In our specialist professions we’ve got to stop thinking of ourselves as one thing. There used to be playwrights, there used to be novelists, there used to be poets. From now on you have to be a writer, and that might mean writing the dialogue for video games, it might mean writing sitcoms as well as novels as well as whatever else. I think we’ve all got to stay nimble. You just go where the technology is taking you.”

Nick is asked if he feels writing relies on rhythm? “Rhythm is a big deal, rhythm of both dialogue and prose. Readers can tell rhythm, audiences can hear rhythm, and I think if you haven’t got it, everything struggles as a result. Hence redrafting really. There will come a point in writing a screenplay and a novel where you’ll hit a rhythm, but it won’t come until some later part of the process. So, you’ve got to go back and make sure you’re there right from the first line, the first page.”

Nick also has words that anyone who writes can identify with. “The real pain about writing is everything is just out of reach, and that’s one of the things that’s so frustrating about being writer. You’re trying to get there and sometimes you can’t and you’ve got to settle for second best. You’ve got to compromise with yourself.”

For anyone getting stuck and battling with ‘writer’s block’ Nick had this advice: “I think that’s absolutely a part of work and you should not worry if you’re unable to write. It may well require you walking away from it or watching things. Honestly music, TV, music, books. That’s what I do is consume – all of those people are solving technical problems in some form or another and it might not be anything to do with what you’re working on but in the end, people are trying to get from point A to point B to point C, in a piece of music and in a book and in a play. Give yourself permission to stop and consume. I think watching a movie in an afternoon when you can’t write is a really great thing.”

-

Photo: From recording by Mark Duffield