Content warning: please note this article references and displays historical racist material

MA Culture Criticism and Curation graduate, Koyuri Sato, credits her parents' initiative to go on regular family visits to museums and galleries across her native Japan, for developing an early interest in the power of objects as vehicles for storytelling and representation. As somebody who struggled with self-expression, Koyuri was innately curious to know how artists conveyed what was in their heads and their hearts through their work. However, it was during the artist, Tatsuo Kawaguchi's solo exhibition talk at Keio University Art Centre in 2020, that she found her calling in curation to tell untold stories. "Kawaguchi told me that artists are people who can express themselves, so he felt it was their duty to advocate for the many people in society who don't know how,"she says.

As a Japanese person with lived experience of the Western gaze, Sato recognises how challenging it can be to remove the gaze of othering when curating representations of foreign cultures and is pleased to see successful examples of large-scale solo exhibitions by Hiroshi Sugimoto and Daido Moriyama in 2023."

I personally found this difficult when it came to curating the CSM Museum & Study Collection’s Japanese Kabuki Actor Print Collection as part of the MA Culture, Criticism and Curation Archive Unit," she reflects. Sato explains that Japanese woodblock prints, known as Ukiyo-e, were mass-produced and affordable, yet they are typically discussed within the context of fine art. "In today's value, these prints would be worth anything between £3 to £10, which is about the price of a coffee and meal from the CSM canteen. I feel like this aspect of Ukiyo-e is not often covered," she explains.

Head of CSM Museum & Study Collection, Judy Willcocks explains that the history of our collection of Japanese colour woodblock prints of Kabuki actors can be traced back in the College's teaching history:

These incredible prints were acquired by the Central School of Arts and Crafts between 1889 and 1903, when a class in ‘printmaking in the Japanese style’ was taught by Frank Morely Fletcher.

I have always been fascinated by the technique used to create the prints; multiple woodblocks had to be carved to build up a full colour image, one colour at a time. However, as a curator raised in European traditions, I could only approach the history and folk tales explored in the prints from my own narrow viewpoint.

Judy Willcocks, Head of CSM Museum and Study Collection

The prints can be traced back to the mid-nineteenth century when – within a few days of opening productions at the three government-licensed Kabuki theatres in Edo – print shops in the cities of Edo (now Tokyo) and Osaka displayed colour prints of leading actors in highlight scenes from plays. Most of the prints in the museum’s collection were made by Utagawa Kunisada (1786-1864), who was the leading designer of actor prints of his day. At his peak, Kunisada produced seven hundred designs a year in his studio with the help of dozens of students and the most popular prints were issued in several thousand impressions. The appetite for actor prints that contributed to its success as a mass-produced artform came from the humble merchants and artisans who enjoyed watching Kabuki plays as a pastime.

After successfully curating a virtual exhibition and video game with fellow students from the MA Curating and Collections course, titled Kabuki Trouble, Sato proposed that there was scope for updating the museum's catalogue descriptions of the prints. Consequently, the museum commissioned Sato to help expand and correct the descriptions, as well as add Japanese characters to each title to ensure discoverability.

-

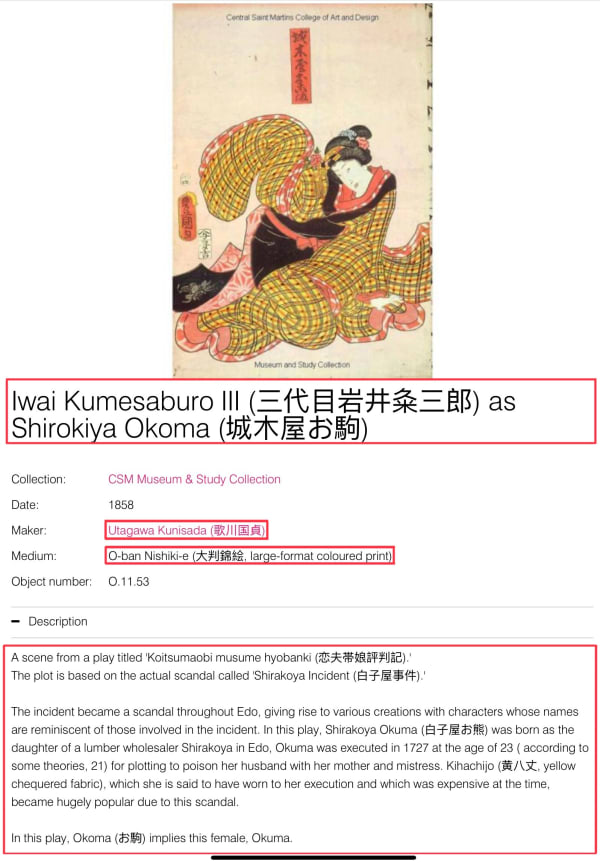

Iwai Kumesaburo III (三代目岩井粂三郎) as Shirokiya Okoma (城木屋お駒) Utagawa Kunisada, 1858. CSM Museum and Study Collection

-

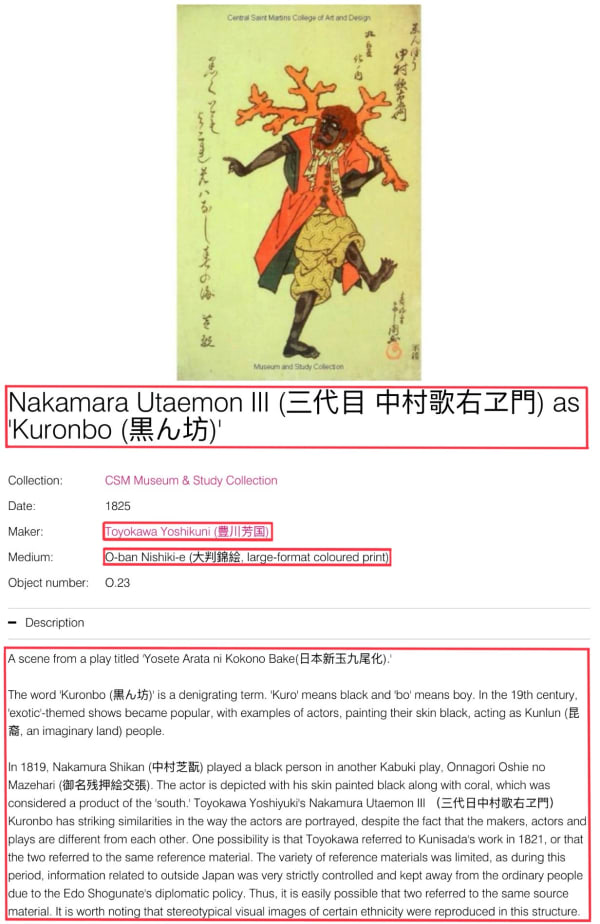

Nakamara Utaemon III (三代目 中村歌右ヱ門) as 'Kuronbo (黒ん坊)' Toyokawa Yoshikuni (豊川芳国), 1825. CSM Museum and Study Collection.

Reflecting with Koyuri

In the interview below, Sato explains the process and her experience of independently decolonising the online catalogue records for the Japanese Kabuki Actor Print Collection between September to December 2023.

When did you identify a problem with the CSM Museum & Study Collection's Japanese Print online catalogue records and address it with the team?

In one of the lectures we had for the Archive Unit, our tutor, E-J Scott, talked about how collection holders should be aware that the very system of collecting and keeping objects is an inherently imperialistic act. Since modern Japan was profoundly influenced by Western attitudes and taste, it is not uncommon to find excellent collections of Ukiyo-e outside of Japan. Woodblock prints were popular exports, especially to Euro-America. As the only Japanese student in my group, I helped my peers research the prints online and discovered inconsistencies in translations by various museums. This made the process of identification very complicated. I also experienced limitations in the amount of information we could obtain from the English descriptions available on the CSM Museum & Study Collections' object records at the time. Therefore, when the group project ended, I came up with the idea to do further research and update the original catalogue records with more accurate information to tackle a structural problem.

It was impossible to include all the prints in our online exhibition and the theme of gender performativity inevitably led to a bias towards which works were selected. For example, during the development process, we came across a print that portrayed a Japanese actor with blackface in a Kabuki play. This print is titled Nakamara Utaemon III (三代目 中村歌右ヱ門) as 'Kuronbo (黒ん坊) in the CSM Museum & Study Collection catalogue. Since it was not directly related to our theme, we put the print back in its archival box and missed the opportunity to showcase it to the public. Later, through closer inspection and research of this print, I discovered a similar print by a different maker and of a different actor in blackface, which suggests that the two makers used the same reference material. This is likely because society's access to information was extremely restricted under the Edo Shogunate's foreign policy. Nevertheless, this discovery provided evidence of the reproduction of specific racial stereotypes, which I believe curators and museums must address.

How did your education and work experience leading up to this project influence your approach?

My experience working as a student curator at my undergraduate university's art museum, Keio Museum Commons, between March 2021 and December 2022, was very influential. In addition to running exhibitions, Keio Museum Commons was an experimental facility that intentionally exposed the anterior of its storeroom to visitors using glass walls. The purpose of this decision was to literally open the collection as much as possible and find ways to remove barriers for audiences. My work experience here inspired me to find ways to make other museum collections more accessible and inviting to the public. Traditionally, collections in the academic sphere have certain difficulties in the way they are presented. As research institutions, we need to ensure academic legitimacy, while at the same time making the exhibitions accessible and meaningful to those who feel they do not belong to the academic sphere.

With this project, my main goal was to restore the original context that had been lost in the dynamics of modern Japan. For example, the play depicted in the print, titled Iwai Kumesaburo III (三代目岩井粂三郎) as Shirokiya Okoma (城木屋お駒), is based on the true story of the Shirakoya Incident; a daughter of a lumber wholesaler Shirakoya in Edo, Okuma, was executed in 1727 after poisoning her husband with her mother and mistress. There are some theories that the Kihachijo (yellow chequered fabric) she is thought to have worn for her execution was expensive for its time and became hugely popular because of this scandal. This goes to show that Kabuki was a source of vogue; ordinary people liked to purchase these inexpensive prints to stay informed about the latest fashion trends.

What were the highlights and challenges you experienced while updating the online catalogue records for this collection?

Considering the collection includes a total of 264 prints, I feel very proud that I managed to add Japanese characters to each title and provide further context and detail to each description. The addition of Japanese characters is significant because it drastically improves the accessibility of this collection for non-Japanese speaking researchers. By including the English and Japanese title side-by-side, such researchers can get an idea of what the print is about and choose to do further research using authentic Japanese sources.

When it came to editing the catalogue record for the Nakamara Utaemon III (三代目 中村歌右ヱ門) as 'Kuronbo (黒ん坊) print I referred to earlier, I noticed the print had a poem written on it that included an offensive term to describe black people. My original draft used a direct translation of this term, but Judy advised me it would be more appropriate to remove this and describe it in a way that is more acceptable in contemporary British society. Therefore, I would say the biggest challenge I encountered was striking a balance between writing authentic English translations that reflected the nuances in the prints, while also ensuring my translations did not offend English-speaking readers.

What are your career aspirations for life after university?

In the New Year, I moved back to Japan to complete my second Masters in Curation at the Tokyo University of the Arts and I will graduate in March 2025. Alongside my studies, I am also doing an internship at the Museum of Contemporary Art Tokyo. To be honest, I do not have a clear vision for my career path just yet. Should I continue my studies by progressing onto a PhD or should I find work as a curator in a museum or gallery? Since my CSM MA dissertation was about Nam June Paik’s robot sculpture and my final project related to digital art curation, I imagine I would enjoy specialising in digital media works.

Reflecting on this fruitful collaboration between Sato and the CSM Museum & Study Collection, Willcocks says: “We always enjoy supporting our recent graduates as they develop and hone their professional skills, and Koyuri’s diligence and generosity has helped us to frame these amazing prints in a more accessible and authentic way. I feel sure she is going to go far in the world of curation if that is the path she chooses to pursue.

Before and after

More

-

Inside/Out exhibition in various Walworth locations, South London. This was part of a student project with Artists Studio Company, November 2017). Photo: Glenn Michael Harper