In an experimental collaboration, the Royal Society and students on MA Art and Science created The Museum of Extraordinary Objects. A collection of provocative objects, the Museum’s role is to start conversations about the future of research culture. Here, we learn more about the project from current MA Art and Science students Stephen Bennett and Julie Light.

How did the project come about?

Stephen Bennett: The Royal Society had initiated a project on the Future of Research Culture. I knew Jo Dally, Head of Policy, Research at the Royal Society, from our time together at the Government Office for Science. The specific need for The Museum of Extraordinary Objects crystallised during some Royal Society events on the Future of Research Culture. Attendees found it difficult to situate themselves outside of the daily grind of life in research labs, lecture theatres and PhD research. Julie and I knew from previous experience that speculative design could open up discussions about future possibilities for research.

What is the role or value of speculative design?

Julie Light: Speculative design is a great way to stimulate a meaningful discussion that isn’t just based on things as they stand in the present. It’s a really useful tool for making future possibilities – things that might be surprising or left field – feel tangible right now. For this project, a speculative design approach meant we could take ideas that the Royal Society wanted to explore for the future and make them into material things that could be examined now by people who might be deeply rooted in their present experience. For example, the Royal Society team were keen to consult about how science might be funded in 2035 – the Museum’s Public Voting Form for a future Science Funding Referendum, complete with ballot questions, was one way of stimulating thought about how the future might be very different from today.

Public Ballot Voting Form, Tere Chad (Photo: Alexander Kent for the Royal Society)

Q: How much did the project express your hopes/fears for the future of research?

SB: The objects developed in the project straddle a line between dystopian and utopian futures of research. Take the Young’s Translator by myself and Amy Starmar (named after Thomas Young, an eighteenth century scientist argued to be the last person who “knew everything”). The artefact asks questions about open access research. There is a modern drive to make results and data available more widely. Yet how useful is this really without a layer of translation, and even synthesis, to make the research comprehensible to those working in other disciplinary fields or even the lay person?

Young’s Translator, Stephen Bennett and Amy Starmar (Photo: Alexander Kent for the Royal Society)

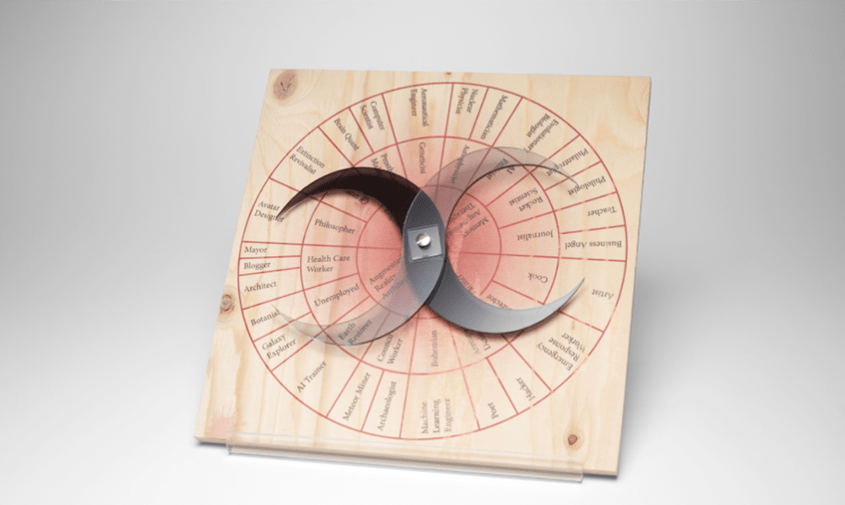

The Interdisciplinary Collaboration Wheel is another example. Researchers being forced to work with those from other disciplines, chosen through a randomised process? That is some people’s vision of heaven – and others’ vision of hell!

Interdisciplinary Collaboration Wheel, Neus Torres Tamarit and Reggy Liu (Photo: Alexander Kent for the Royal Society)

Q: The Museum’s objects highlight facets of research that are often invisible such as collaboration and failure. Was there a particular impulse to shine a line on unseen things?

JL: The Royal Society’s Changing Expectations project is all about discovering how the invisible aspects of science research – that fundamentally shape people’s careers and experiences of working in science – might be improved. One of the main reasons they wanted to work with artists on the project was to explore how to make abstract ideas about ‘research’ and ‘culture’ – doubly obscure when you use the two terms together – into something that people could discuss creatively.

It was a great challenge initially for all of the artists to get our heads around their priorities and then to find ways to make them easy for others to engage with. The Museum, bringing together a series of objects from the future, each of which reflected on these hidden themes, was what came out of that process.

Q: Is there something particular about the MA Art and Science landscape that means this project could only have come from it?

SB: The project is at the heart of what the course does: artists engaging with science issues, not just to prettify them, but to stimulate new thinking. The project required – and promoted – interdisciplinary thinking. Students on the course engage with complex and varied science issues on a daily basis, producing artwork on topics as varied as particle physics, neuroscience and ecology. This meant we were quickly able to engage with the concepts relating to the future of research culture, and render them in a visceral and tangible way.

As a result of this collaboration, our artwork has been shown, touched and interpreted by over a thousand scientists at over a dozen events around the UK. The Royal Society cite the work as having opened up better conversations about the future, providing their project with richer insights on the future of research and it’s now using that information to build a programme to achieve a better research culture in 2035.

More information: