With Degree Show season now behind us, we continue to take a look at our students’ final projects and the inspirations behind them.

In her dissertation, BA Fashion Communication: Fashion History and Theory student Momo Hassan-Odukale examines style as a political tool – specifically the relationship between black British women, style and politics from 1940 onwards. Hassan-Odukale proposes that race has been fluently established in Britain by dissections of the cultural body through dress and style. She examines how black migrant women in Britain fought to control and conciliate their identities through style, while simultaneously highlighting the prominence of colonial, postcolonial, gendered and beauty discourses. Hassan-Odukale uses three case studies to assess distinct segments of the Black British woman’s cultural and political reality. Here, she writes about five integral themes which comprise her final thesis.

1. Identity

The word identity was extremely important in my thesis. I had to unpick the different ways of understanding identity – ways specific to the Black British female. As it is a word that is in many ways undefinable, this required research across three different generations of Black British women. First generation migrants who made up the first large settlement of non-white peoples in Britain were prescribed a new identity as they landed: “Black.” Previously, they had referred to themselves as “West Indian” but they became “Black British” during the sixties, forming a new enforced identity. With African migrants arriving a few years later, the all-encompassing “Black” identity in Britain overshadowed the genuine, heterogeneous traditions and cultures of the Caribbean and African peoples. Thus, this united “Black” identity was a concept which existed more in the imagination of white Britons, and less in the reality of black lives and cultures. Each generations’ creative employment of style reflects a changing “Black British” identity. The story of black women in Britain is a precarious quest for identity and one of constant rejuvenation.

Photo courtsey Momo Hassan-Odukale

2. Dressmaking

The skills of sewing and dressmaking carry heavy cultural weight in the African diaspora – it is a skill which many used as a survival tool. Those who possessed the skill had the opportunity to break through barriers — social, economic and psychological. Dressmaking for the black female is not so much about the end product but the skill in itself. The freehand method, particularly common with black dressmakers, is significant for its process of rejecting ready cut patterns. Instead, the dressmaker quite literally draws their designs freehand, even cutting directly into the fabric. In this chapter of my dissertation, I look at the choice of the freehand method as symbolic in a wider sense, serving as an allegory of the feeling of the Black British community at various points in history. I argue that its employment by black women is representative of the predicament of the community at large: simultaneously wishing to be free from the pessimistic ready cut futures laid out for them in Britain, while faced with the inescapable need to survive economically through whatever means.

Photo courtsey Momo Hassan-Odukale

3. Traditional clothing

In the 1960s, in a society such as Britain, where outsiders and newcomers faced xenophobia and discrimination, to wear traditional clothing was to effectively “Other” oneself. Assimilation is at the heart of most early migrant experiences, often not as a choice but as a method of survival. The choice for many Caribbean and African women to use traditional dress as one of their main tools of resistance, both overtly and covertly, is understandable, yet confounding. Traditional dress within the Black British community evolved with politics. For example, the Afrocentrism of the second and third generation, reflected in clothing, indicates hybridity and a different experience of “blackness” to that of the Windrush generation. Traditional clothing allowed women throughout generations to challenge assimilation, celebrate their heritage and present the “real” them in the face of overt racism.

The fact that the first Notting Hill Carnival in 1959 (then termed as the Caribbean Carnival), the largest celebration of Caribbean heritage dress, was a response to the aftermath of the 1958 Notting Hill race riots is a clear indication that black women used traditional dress as a political tool in British society. The freedom of style expressed in outfits worn at this event, as much as any other aspect, is symbolic of British Caribbean culture; it is because of women such as Claudia Jones, who organised the event and is often described as the “mother of the Notting Hill Carnival”, that this can be said. In this chapter I explore studio photography of the time, as women and their families went to have their portraits taken, sitting for their photographs in traditional clothing. These portraits allowed migrant communities to preserve their origins while documenting their progression as black Britons – these images were often sent back to their families in their homelands. Representing traditional dress was fundamental to women in the diaspora; their bodies here were used in the struggle for liberation, their employment of dress disclosed and concealed in the development of their identities.

Photo courtsey Momo Hassan-Odukale

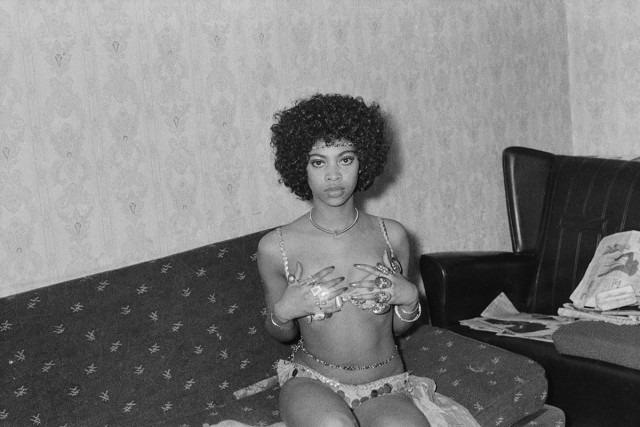

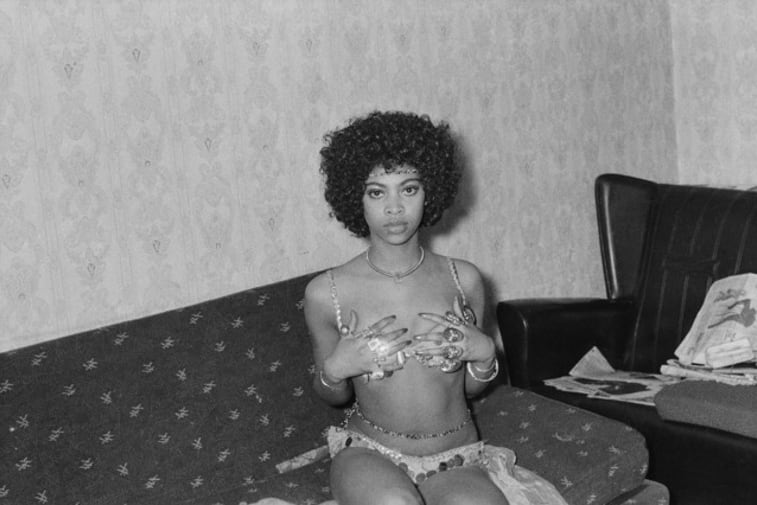

4. Hair

Black hair is a visible marker of blackness, and so, of difference. It is second only to skin as a racial signifier. Black hair has been utilised as a tool of resistance for as long as it has been used as a rationale for scientific racism – as seen in early anthropological works which listed hair as a category for racial classifications, from which dehumanising stereotypes were created. In late 1960s Britain, women who started wearing afros rejected all artificial beauty regimes, such as the relaxing of hair and the bleaching of skin. The birth of the Black Power movement encouraged more black women to appreciate their beauty and to query the European standards of beauty that had been thrust upon them since girlhood. The afro was symbolic both in its rejection of straightened styles and short, “conservative” haircuts. With the help of an afro comb or pick the hair was encouraged and teased outwards and upwards into its characteristic rounded shape. Today, it is evident that personal preference is central to the choices made around hair for black women – even within natural and relaxed styles there is an abundance of options.

Photo courtsey Momo Hassan-Odukale

5. Windrush Scandal

In my thesis I look at women from the Windrush generation at the start of every chapter. It was very clear in 1958 that ideas of citizenship and “Britishness” remained tied to whiteness. Today, despite progress over generations, black people and particularly black women have remained the “Other” in society. At the end of my thesis I talk about the Windrush scandal of 2018, which saw many of the first generation of Caribbean migrants, who have worked, lived and been educated in Britain denied citizenship, labelled outsiders and forcibly deported. This example shows how important this topic is and how many issues of identity, belonging and racism prevail today. Approaching this socio-politically charged topic through the lens of style gave me fresh insight into the political lives of Black British women, who have consistently been rendered silent entities. Their politics, struggles, resistance and protests are woven into the very fabric of the clothes they made, chose, wore and passed on to the next generation to continue the fight.

More: