“I remember a specific day after I was hurt as a child, and my aunty took me to hospital to change the tubes in my tummy. We were just in front of a school as two large bombs came over the border from Iraq. They hit the school. Mum and my aunt found the bodies of children. They tried to put the bodies together, so the children had their own body parts.”

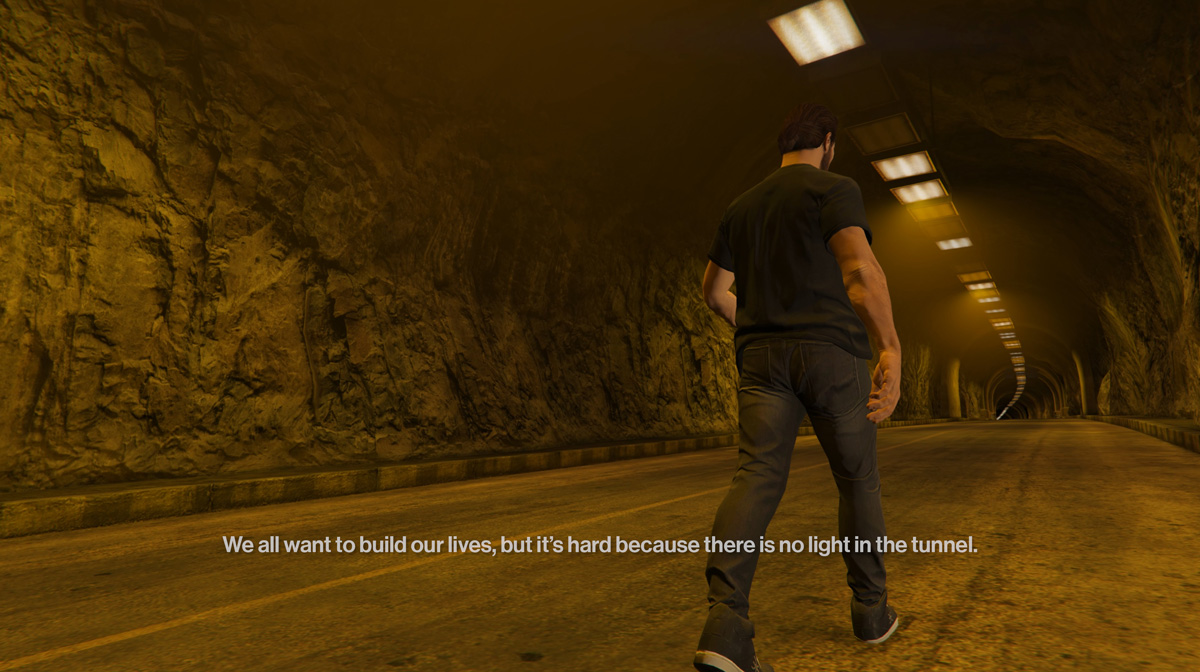

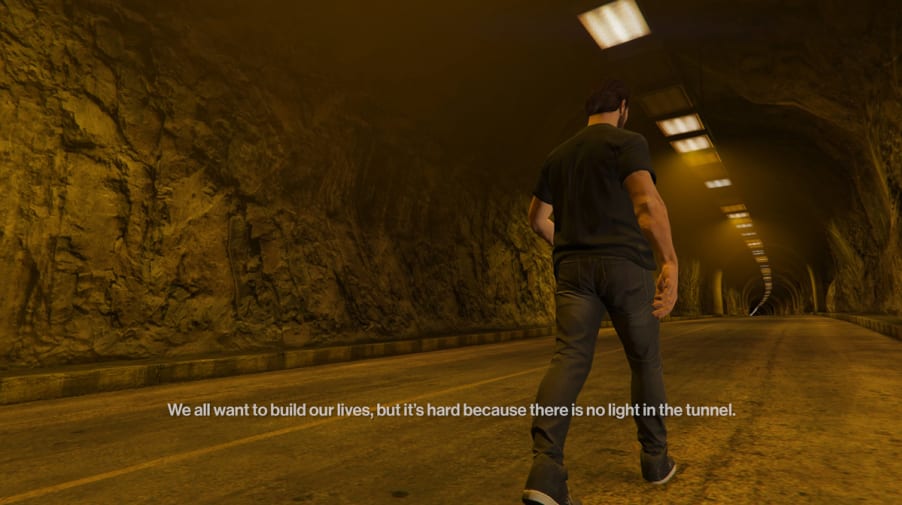

This is a very real story told by a very real person, but through virtual means. The man is presented as a character in a video game. He walks through virtually-created landscapes – up hills, across valleys, through dimly-lit tunnels – while a male synthetic voiceover narrates.

Dressed in a grey t-shirt and jeans, the avatar’s identity is unknown, shaped only through vivid, often harrowing memories of surviving the Iran-Iraq war and fleeing Kurdistan for Europe. “I walked from Iraq to Turkey through a minefield. A lot of people died walking there. We thought: we walk towards freedom.”

This is Arya’s story.

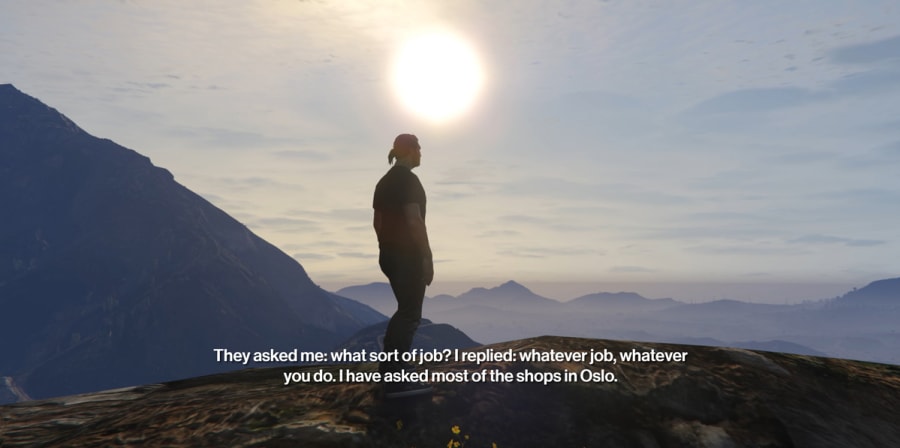

“I am a woman and I am morally tortured,” says a female automated voice, as a woman in the video game walks on train tracks across a barren landscape. She describes her plight during the Ethiopian-Eritrean war and how she fled to Saudi Arabia with a fake passport and worked as a cleaner. “Politicians are selling us for their purposes, innocent people are being tortured and killed.”

This is Sara’s story.

Arya and Sara are members of Meneskir i Limbo (People in Limbo), a group of self-created paperless migrants based in Norway, and they share their stories of identity and migration in FF Gaiden: Delete – a virtual film by artists David Blandy and Larry Achiampong. It forms part of a series of FF Gaiden films created entirely using the virtual space of the video game Grand Theft Auto V and made in collaboration with marginalised or voiceless groups.

“We persuaded the authorities to let us bring a PlayStation 4 into the prison. We didn’t ask [the prisoners] to talk about their experiences or incarceration, it was just a space for them to be creative." – David Blandy, artist

Inspired by the lost plays of Frantz Fanon, a psychiatrist and political radical, the FF Gaiden films – just like the Finding Fanon Trilogy the artists made before – continue themes Fanon explored about postcolonialism and colonisation, extending these ideas to a digital space. Blandy and Achiampong’s films are a fantastical quest to examine the politics of race, racism and decolonisation, and how these societal issues – in an age of new technology, popular culture and globalisation – affect our relationships.

“We didn’t want it to just be about our story, we wanted it to be about everyone who is at the sharp end of neoliberal politics – people at the borders or in incarceration,” explains Blandy. “These are contested spaces created by a system in which some people are privileged, and other people are excluded, and that’s the basis of our societal structure.”

The game’s built-in video editor and camera allowed the pair to put the subjects into a readymade landscape in which they could create their own avatars and narratives. Blandy and Achiampong invited two members of People in Limbo to build avatars of themselves that could navigate around the game’s lush and varied landscape while they relayed their turbulent stories. Blandy continues: “It gave them a free voice because they were effectively anonymous, just shown through an avatar. You would have to know their case intimately to work out exactly who this person was. It became like a mask the people could wear to express something honest and true.”

Anonymity through a video game may create a more comfortable platform for the storytellers to voice their experiences, but it poses uncomfortable questions for the viewer about the fetishising of refugees. Listening to the monotonous tone of a synthetic voice describe traumatic scenes while the avatars traverse a digitised world, you begin to wonder if using video gameplay risks turning real injustices into fantasy or entertainment. Yet the stories are so affecting that it is hard to consider them mere fabrications; instead of dehumanising the characters, they tap into our awareness of the crisis of displaced humanity around the world.

For Blandy and Achiampong, this medium highlights inherent cultural biases within video games, even down to the limited and generic options for avatars of different ethnic backgrounds. “It’s totally dictated by stereotype,” adds Blandy. “I think it’s unconscious in that the majority of the makers are white, 30-something blokes.” It also allows groups to express themselves creatively to cope with trauma. For the film FF Gaiden: Control, the artists collaborated with veterans at Altcourse Prison in Liverpool. Blandy says: “We persuaded the authorities to let us bring a PlayStation 4 into the prison. We didn’t ask [the prisoners] to talk about their experiences or incarceration, it was just a space for them to be creative. They all created avatars and short stories. Some wrote songs and incorporated it into the film.”

While the FF Gaiden works are reverent in tone compared with Blandy and Achiampong’s earlier collaborative work, they slot neatly into the themes running through the duo’s artistic output about displacement and racial identity. As Blandy puts it, his work is driven by ‘my lack of a true feeling that there is a place for me.’ As a young white boy from inner-city London with a love of hip hop, Blandy sought to make sense of his interest in something that belonged to a predominantly black culture.

He addressed this schism with Achiampong, who is of Ghanaian heritage, by forming a hip-hop crew called Biters. The tongue-in-cheek project saw the pair recite famous rap lyrics for arty crowds as a comment on the absurdity of identity. “It was poking fun at ourselves and masking the pain and emotional core to both of our works; the feeling of being trapped in one’s own skin,” says Blandy.

Much of Blandy’s and Achiampong’s solo and collaborative work focuses on racial prejudice and self-analysis, predominantly using a humorous voice (“We saw the humour in the hubris of creating a hip-hop crew”). With the FF Gaiden series, told through unheard voices, the tone became more deliberate, sober – but no less creative. The latest voices to contribute to the series are students at LCC who, through the Visible Justice public programme, are expressing concerns around surveillance and data harvesting. These areas Blandy hadn’t thought of, but he recognises their generational relevance to a group who is – like the rest of us – ‘very much enmeshed in a system’. “I think they are anxious about how much their actions and their thoughts are being decided by algorithms and the digital environment. It’s a legitimate and worldwide concern.”

Blandy points out that some of the students are first generation Chinese and are particularly interested in the mechanics around the social media platform ‘WeChat’ in relation to government surveillance and social rating scales. “These things are a reality in China, whereas here it’s like Black Mirror-type science fiction,” he adds. “But maybe we are much closer to that than we’d like to think.” Systemic injustices restrict our freedom: of movement, of thought, of self-expression. Watching avatars navigate the digital, rigidly-coded world of a video game while sharing their experiences of injustice seems to heighten your awareness of these limitations and the intersection between reality and fantasy, identity and inequality. Though we are all, to varying degrees, trapped by our societies, it is ‘the people at the borders or in incarceration’ who Blandy speaks of, and offers a voice to in FF Gaiden, that are still waiting to feel free and accepted by the world. As long as social injustices exist, they will always be people in limbo.

Words by Dalia Dawood and Eric Thorp for Visible Justice.

Visible Justice takes place at London College of Communication from Wednesday 17 April to Friday 3 May 2019, and is free and open to all.

- Find out about London College of Communication's Media School

- Explore events at London College of Communication

- Follow LCC on Instagram to see behind-the-scenes at the College