London College of Communication Photojournalism and Documentary Photography lecturer Lewis Bush has released new photobook ‘Metropole’ – exploring, researching and photographing property developers and developments in London.

Part funded by a grant from LCC Research and published by Overlapse, 'Metropole’ is one of a number of external photographic projects by Bush loosely exploring themes including finance, war morals, intelligence, and social justice.

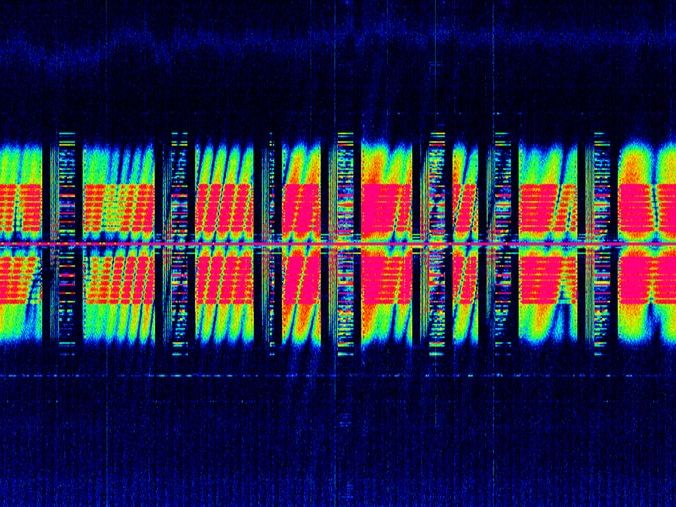

Previous projects have included ‘Shadows of the State’, a photobook investigating and exposing mysterious radio broadcasts dating back to the Cold War, and Lewis brings this expertise and interests to his teaching at LCC, and students benefit learning from an active writer, curator, and photojournalist.

We caught up with Lewis, who teaches on both BA (Hons) Photojournalism and Documentary Photography and MA Photojournalism and Documentary Photography at LCC, to find out more about ‘Metropole’ and to get an insight into some of his future projects.

Hi Lewis, can you tell us a little more about Metropole?

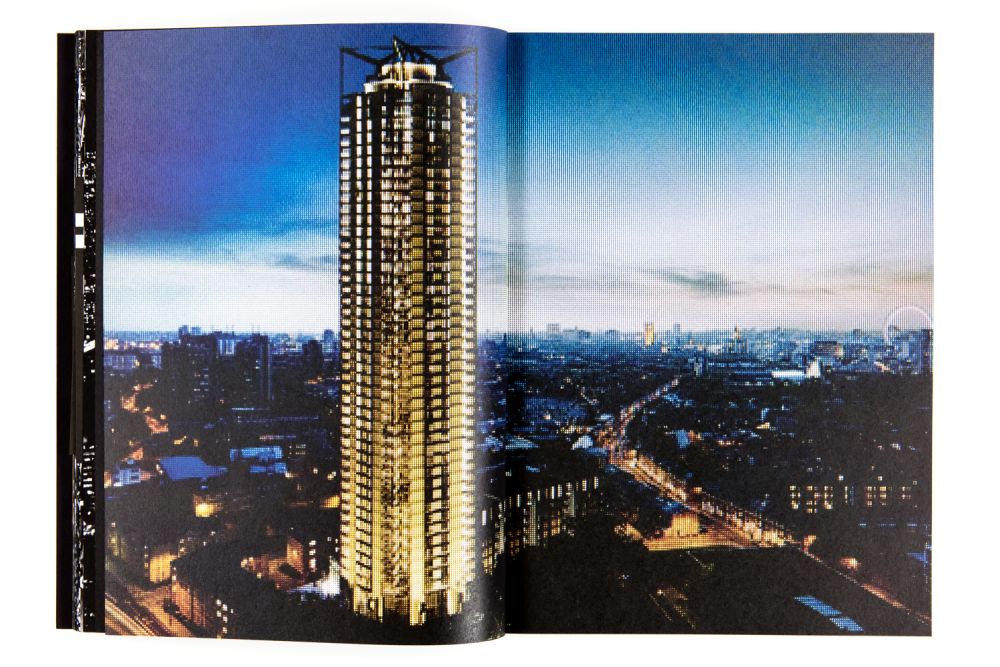

Metropole is the result of three years of work photographing and researching property development in London. The series began as quite a visceral photographic reaction to the feeling that I was losing the city I had grown up in, as more and more of it was redeveloped by unsympathetic developers who had no qualms about wiping away the city’s existing architecture and people.

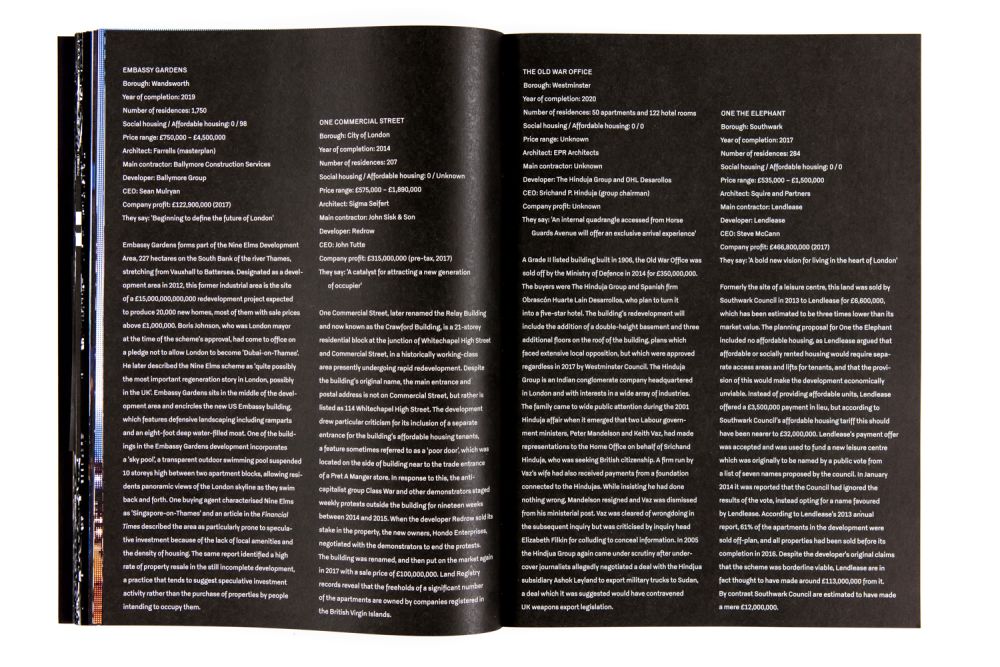

Over time that sense of anger has also been augmented with a great deal of research looking at the tactics and schemes that many developers use, for example to get planning permission without meeting council requirements for things like affordable housing, or how some of them employ complex financial structures and offshore jurisdictions to amplify their profit and minimise their taxes on UK based projects.

What inspired you to create a photographic project on this subject?

The sense that the city I had grown up in was disappearing very rapidly. When I was a kid I still remember a huge number of derelict or semi-derelict buildings, empty plots of land, and so on, even in the centre of the city. The city was just a more interesting, varied place.

We often hear that photography has no power to influence events in the world, and to some extent that’s true, but the power of photography to scrutinise the activities of the powerful is an important one, and it is a power that clearly still makes these people quite nervous — Lewis Bush

As land values have increased these things have inevitably disappeared, and the city has become more homogenous and boring. But behind that homogenisation there is also a human cost, of communities displaced and people forced out from the city they once called home.

This is a continuation of your work from 2015. How do you feel the subject matter has changed in that time? What do you feel the big differences are?

If anything, the problems seem to have been magnified since 2015 when I published a small zine containing about dozen images from the project. I’ve watched since then as development has very visibly radiated out along major roads from the centre of the city and into areas I didn’t really imagine would ever be attractive to developers.

I grew up around Peckham and New Cross, places which felt so off the map when I was younger that I never could have imagined a time when local people would be battling to prevent aggressive redevelopment projects in these areas.

How did you put this work together?

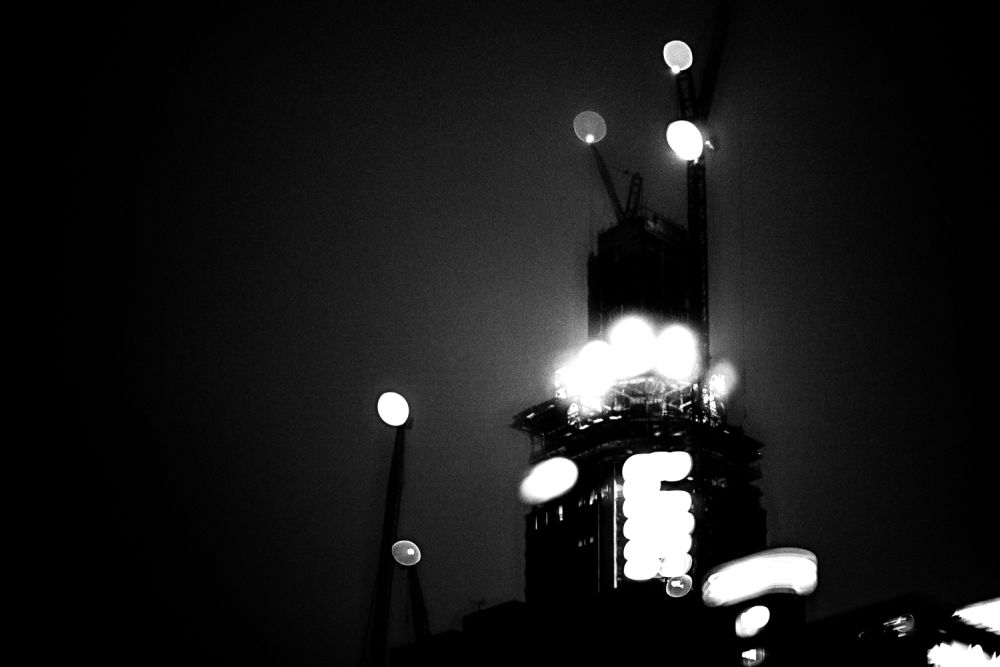

Very simply by heading out into the city during winter nights and walking for some distance through areas that were particularly subject to redevelopment. In the latter stages of the project I travelled more widely as new developments began to appear further afield from the centre.

On finding construction sites or buildings that fit the bill I would then explore them photographically, layering multiple images of them over each other inside my camera to create the multiple exposure images that give Metropole its particular look. I’d then often go away afterwards and conduct research on the building I’d photographed.

Sometimes the process was reversed. I’d research a location in advance and then specifically travel to visit and photograph it. Gradually these images were constructed into a narrative, a draft book and now, finally, a finished publication.

Metropole

What was the highlight?

It’s hard to think of the highlight to a project about a topic which so utterly depresses me, and where much of the time spent shooting was cold, isolating and tinged with a degree of threat. I guess the regular encounters with people working on these buildings, and the threatening undertones of these exchanges felt like something of a perverse achievement. We often hear that photography has no power to influence events in the world, and to some extent that’s true, but the power of photography to scrutinise the activities of the powerful is an important one, and it is a power that clearly still makes these people quite nervous.

Your work is being featured in London Nights – can you tell us a little more about the show and your work that is being shown in it?

The exhibition is a major show of photography, both from the museum’s collection and loans from a large number of artists and photographers. I was involved from quite early on in a minor advisory role, so it’s been great to see the exhibition develop and grown since then under the guidance of the museum’s photography curator Anna Sparham, who has brought together a really interesting array of work covering an impressive span of the history of photography.

At its heart I think Metropole is about the negotiations that take place over the space of the city, and what happens when those negotiations visibly break down. — Lewis Bush

The exhibition is broken down thematically, reflecting on different issues that the urban night presents, from the pleasure and thrill seeking, to threat and isolation.

What do you hope for audiences to take away from your work?

I hope people take away a sense of anger at what has been allowed to happen in London by successive mayors and councils, and I hope to some extent it adds to the historical record of this time. I really believe people will look back in decades to come and wonder what we were thinking by allowing some of these projects.

A city is owned by all the people who live in it, and we elect officials to represent our interests equally and fairly. Too often it seems that they instead end up representing the interests of powerful organisations and individuals with little real investment in the city, who are only interested in it for the opportunity to make money or make a statement about themselves.

At its heart I think Metropole is about the negotiations that take place over the space of the city, and what happens when those negotiations visibly break down.

What do you plan to work on next?

I’m currently working on two projects. Throughout 2018 I was photographer in residence in the Bailiwick of Jersey, a channel island best known for its large finance industry. Here I’ve been making work exploring different aspects of finance, and I plan to continue looking at this when I return to London in the autumn. It has a lot of connections with Metropole, both in the sense that lots of London developments are owned offshore for tax reasons, and also in the sense of the City of London being a key financial district with strong links to Jersey.

Alongside that I’m working on another project about the space race, and specifically the lunar landings which celebrate their 50th anniversary next year. In this project I am looking at the life story of Werner von Braun, the architect of the rockets that made the lunar landings possible. What is less well known is that before von Braun worked for NASA he helped to engineer the V2 rocket, a World War II terror weapon which killed thousands in the closing stages of the war. The project is about the moral complexity of people, set against our desire for simplistic narratives that paint people as heroes and villains, and by association it is also about the perceived morality (or immorality) of technologies.

Words by Dayna McAlpine, BA (Hons) Journalism graduate.

- Find out about LCC’s BA (Hons) Photojournalism and Documentary Photography and MA Photojournalism and Documentary Photography courses.

- Learn more about LCC Research.

- Discover the perfect course for you at an LCC Open Day.