At London College of Communication, our research community is home to world-renowned practitioners and theorists who make a vital contribution to our creative culture through a range of activities such as collaborations, partnership projects and doctoral work.

Our second doctoral work-in-progress exhibition, Unfolding Narratives 2, highlights 7 of our PhD students at various stages in their academic journey. Connecting conceptual thinking with practice through explorations of themes such as the body, culture, identity, gender, race, ethics and narrative, this exhibition aims to celebrate the emergence of new and compelling work while inviting wider audience engagement and feedback.

To mark the launch of Unfolding Narratives 2, we caught up with our exhibiting students to explore their practice, current projects, and creative journeys so far.

Manuel Francisco Sousa

Manuel Francisco Sousa works with documentary photography, portraiture and printmaking. His doctoral thesis offers poignant reflections on the relationship between image-maker and participant, and explores how ethical considerations can be made more visible within the field of photographic practice.

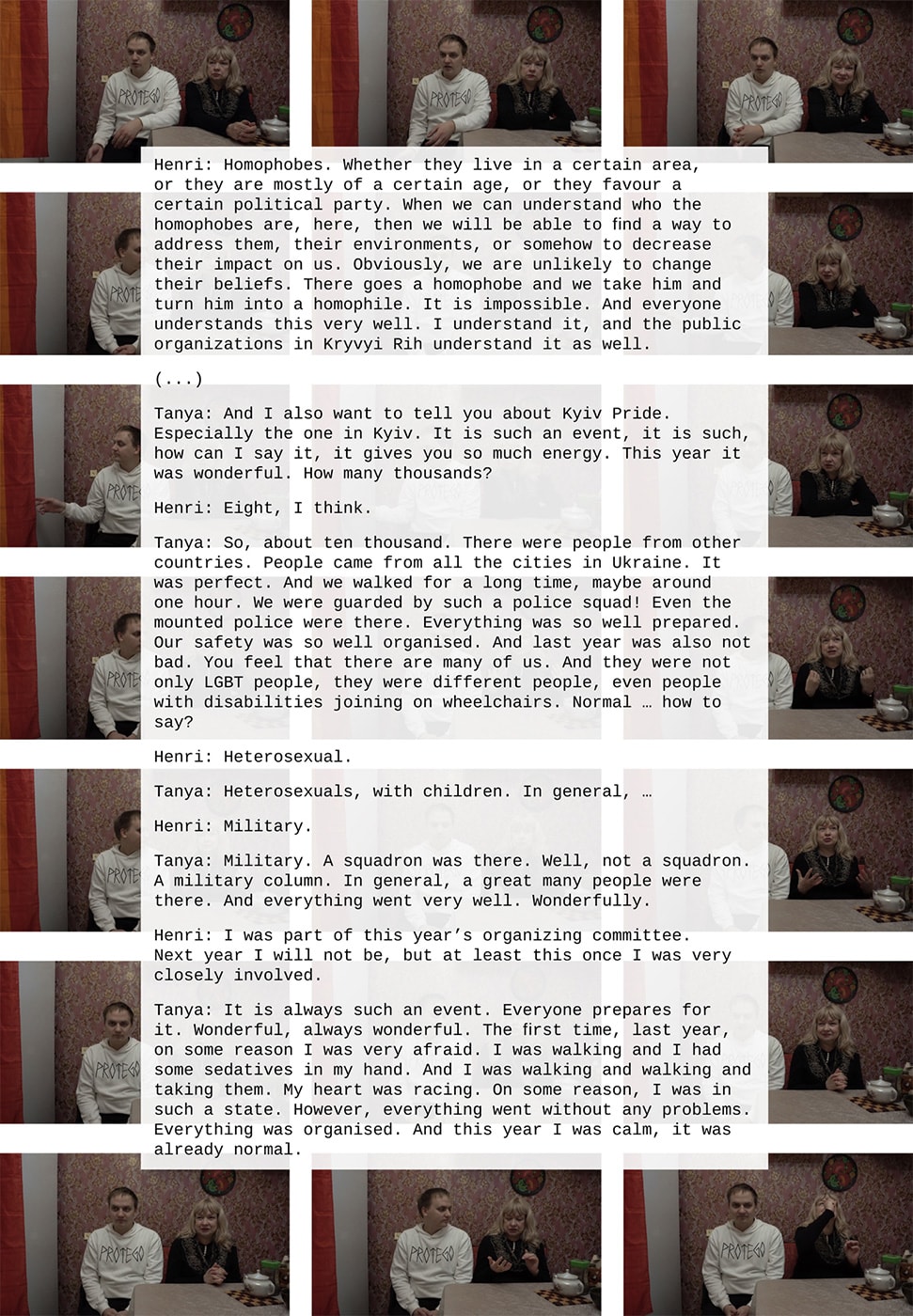

More broadly, Manuel is interested in foregrounding the conditions in which photographs of the other are created, alongside exploring the agency of participants in their own photographic representation. Working with mutual narratives and collaborative processes, he has developed projects internationally across Portugal, Brazil and Ukraine, where his practice has enabled him to share stories of people and place.

We talked to Manuel about developing narratives around the other, the power dynamics of speaking and telling, and the value of creative collaboration.

Have you always had a passion for your field of study, or is it something you gravitated to over time?

Taking pictures of others - and more specifically, portraiture - has always been central to my practice in both documentary and non-documentary contexts, but as I started to move more to documentary modes of working, my interest in questions of voice and representation in photographs also increased. I started engaging with collaborative methods, and eventually, I focused on the encounter between photographer and participant in the field, with ethics as the ground for this relationship.

Does your practice have a central ethos, theme or message?

My definition of documentary photography is the representation of others. It’s a kind of story-telling of an other. Here, I purposefully separate the 'story' and the 'telling' components of the word to refer both to the self of the story and the voices which speak within the space and process of photography-making.

In my practice, I aim to foreground and make visible the conditions in which these photographs are created – I consider this to be an ethical question. Levinas calls ethics that which challenges me in the face of the other. As a practitioner, the ethical relation created by my own encounter with the other positions and questions me in my own perspective. In this sense, knowing the other is something that is placed within the scene of address; it’s a relationship.

What inspired your PhD project, and what do you aim to achieve through your work?

My goal is to contribute to a more emplaced and generative understanding of the ethics and frameworks of documentary photography practices in relation to their participants, but the idea of a goal also carries an idea of purpose.

When I use the word ‘photography-making’, for instance, my intention is to highlight the relationship between practitioner and participant in their act of doing. It's a gesture to position ethics as the centre and the ground of that relation. This is important because ethics then becomes something that is participated in. It questions what it is to know the other, to tell the other, to tell a story of the other.

It reflects on the visibility and authority of voice, and more importantly, the visibility of ways in which power and sovereignty are exercised over places of speaking and telling.

What is your creative process like?

My methodological framework primarily comes from anthropology. I needed an approach that spoke to being in the field in relation to the other, and to an idea of ethics as something concrete, tangible, and emplaced.

In my fieldwork, I explicitly discuss and share aspects of control over our photographic encounters with participants, which includes their review of my edits. It’s an ongoing conversation where I’m interested in how they speak of their experience of our encounters, their accounts of both themselves and me, and how they view what I tell about them in my own voice. This becomes represented in the work in multiple ways such as drawings or texts. I then bring these different interventions together to talk about those encounters.

My own autoethnographic voice positions me within the process of photography-making, and attempts to unsettle, subvert and make visible the authoritative voice of the photographer.

Why did you decide to undertake your PhD at LCC?

I studied on MA Photojournalism and Documentary Photography a few years ago. During that time, I became more actively interested in the questions I eventually wanted to develop into my research. I also already knew my tutors from the course, and so I decided to apply for a PhD at the College.

Of course, my understanding of those questions has changed over time, and they have in turn elicited new questions themselves - but for me, there's a path from then to the work I'm doing now.

What have been the highlights of your experience so far?

It’s difficult to briefly summarise these 3 and a half years of study, the network of people and events at the university, and the ongoing support of my group of colleagues as we've gone through several stages of the PhD. There have been many highlights so far, but I will mention only a few.

First, on a personal level, is my ongoing fieldwork in Ukraine. I’ve had the opportunity to meet some very generous people who have shared their trust and stories with me. I use the word ‘personal’ to mean ‘as a practitioner’, but also to emphasise the human aspect of being. Some of these encounters questioned me very strongly, and helped me to understand my own position as a practitioner, as a researcher, and more. These experiences are something invaluable that I’ve been given by the people I’ve been working with.

Additionally, I’ve had some very interesting ongoing interviews and conversations with a few practitioners whom I consider as references. I was also invited to organise and lead a multidisciplinary seminar in Kyiv with researchers and practitioners from related fields, where we discussed concepts of ethics and storytelling in their approaches. That required some work, but it was a very rich experience and helped me position myself in relation to different and local contexts.

And, finally, the work with my supervisory team – Dr Paul Lowe, Dr Jennifer Good and Dr Christopher Wright – has been an essential and formative experience. This has guided me into exploring new approaches to writing, the learning of new methodologies, and better understanding and shaping of the framework and objectives for my own research.

Related links:

- Explore more of Manuel's work on his website.

- Learn more about selected doctoral works in Unfolding Narratives 2.

- Find out more about Research at London College of Communication.