In this conversation, Adriana Cobo Corey shares her PhD research on taste, space and power. See her work in (In)Visible Processes at the Lethaby Gallery curated by MA Culture, Criticism and Curation students. The exhibition shares recent PhD research from across disciplines to demystify the work and unravel its mechanisms.

Why did you do a PhD?

Being an architect, I have always been very critical about my own profession. I taught but had become disillusioned by academia. Central Saint Martins, being an art and design school that has a Spatial Practices programme including architecture, made sense to me as an interdisciplinary context from which to critique the discipline.

What was your subject?

I started thinking about taste and the problem of author-based architecture. How architects are the central protagonist of their spatial opera, largely regarding themselves as ‘taste makers’.

The profession has used taste to legitimise what architects do from the moment it was institutionalised. In the minutes of the first meeting of Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA), there is a key sentence that defines present and future architects as “men of taste, men of science, men of honour”. A troubling stance in so many levels.

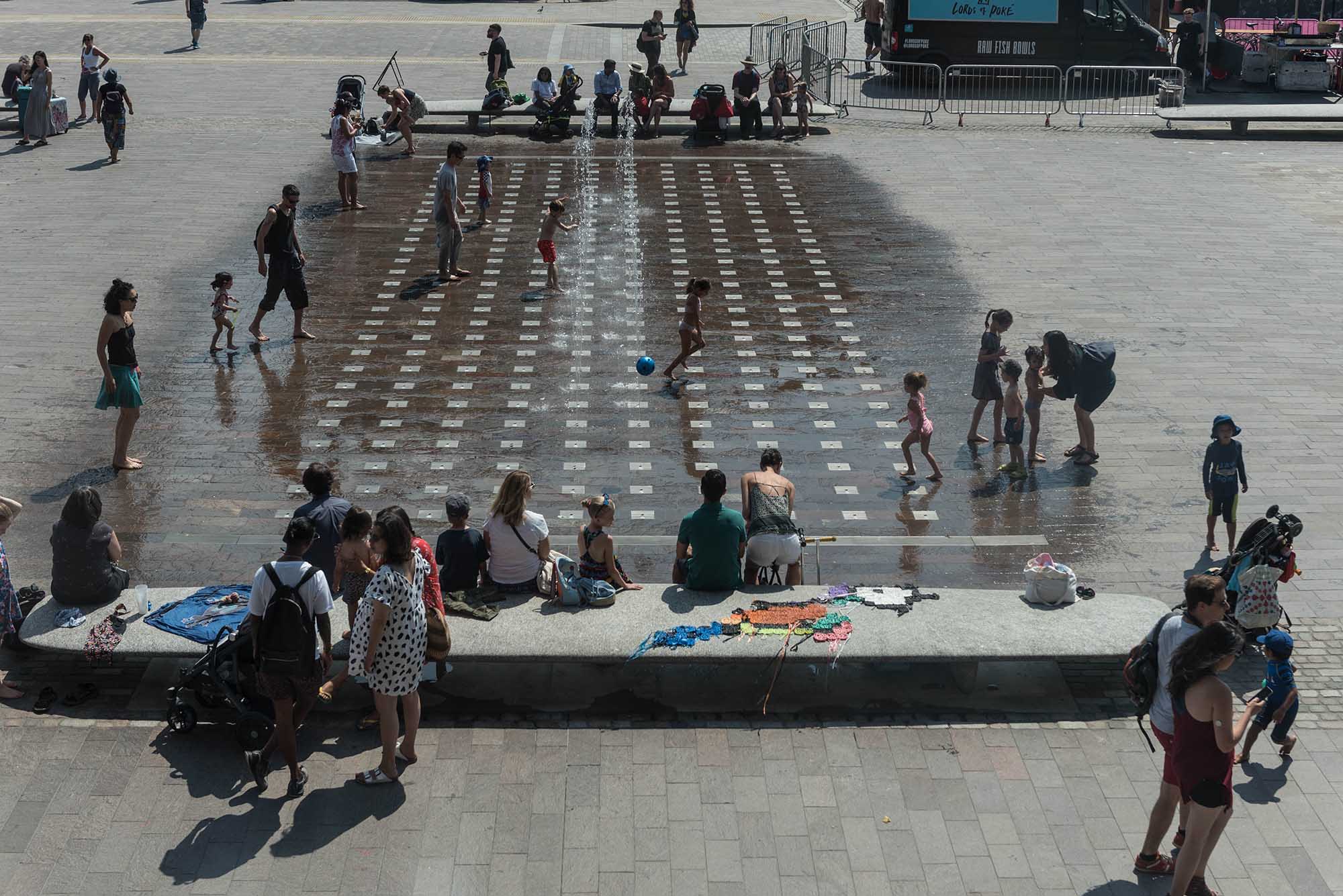

At the same time, studying at Central Saint Martins, I was developing a love-hate relationship with Granary Square – the public space at the heart of the privately owned King’s Cross estate where the College sits. The fountains were getting in my psyche: the sound of water and the presence of playing children which, as beautiful as they may look, are also co-opted to legitimise the privatisation of public space as successful. Mainly, I argue, through controlled and targeted aesthetics.

So, I decided to explore how the politics of taste in architecture play out in public space – its design and management, its accessibility, maintenance and user programmes, specifically on Granary Square.

I have embedded memories of women washing clothes in the river that ran through my rather posh grandmother's neighbourhood in Cali, Colombia, where I saw a clash of classes and spatial use. These women were uncomfortable reminders of privilege for more affluent local residents. Back in Granary Square, I felt I needed to insert their presences into the space to articulate and make visible a chore, a labour, a maintenance.

How do you punctuate the privately owned public space?

My first PhD project was a series of laundry sessions washing clothes on the fountains of Granary Square. I put myself into the space, doing the laundry and sleeping on the benches but to momentarily shift the controlling power structures I realised that I needed to collaborate with its workers.

For my second project I collaborated with a group of cleaners from the KX Estate services. Together we devised a way for to draw on the floor using their cleaning machines. They were still acting within the framework of their work – and being paid – but they had agency to make their own marks. They became more visible as performers for three months, as we drew while cleaning the square every other Monday morning.

-

Disappearing Garden Project with Halil, Cem, Daniel, John, Benjamin, Mathew and Adriana, Adriana Cobo Corey (Photo: Catarina Heeckt)

-

Disappearing Garden Project, Adriana Cobo Corey (Photo: Catarina Heeckt)

-

Granny Square, Adriana Cobo Corey (Photo: Catarina Heeckt)

-

Granny Square, Adriana Cobo Corey (Photo: Glenn Michael Harper)

For my last project I worked with a local group of senior female citizens to crochet covers for the benches in Granary Square. Our work is exhibited in the current (In) Visible Process exhibition at the Lethaby Gallery.

As daily users of those spaces and buildings, how are we complicit in that existing power structure?

I cannot help being a white, middle class woman. My Latin American collaborators, the maintenance workers for example, only have to hear me speaking in Spanish to know our difference.

But there are points of convergence. And there's identification in resisting the structure with these points of convergence. I spoke with the maintenance workers and said “when I see you working, I see you drawing not cleaning”. And I spoke to them as a woman who cleans her house, “I know that your labour is invisible because mine is invisible at home. I reckon you don't like that because I don't like that either.”

Are you hopeful for these spaces?

For a while I thought that I was going to save the world from the privatisation of public space through activism. I will not; it is David and Goliath. But one can design beautiful moments of agency.

Taste is a maintenance practice, it maintains certain kinds of architecture and power structures. Taste is an aesthetic practice of control and a reflection of power; civic life is constrained by that. My practice is trying to understand how to counterbalance that, how can we, even if temporarily, disrupt and negotiate that controlling element.

See Adriana Cobo Corey's PhD work, alongside many others, in (In)Visible Processes at the Lethaby Gallery until 22 January 2022. The show is curated by MA Culture, Criticism and Curation students.

-

Image taken by Alys Tomlinson

-

Inside/Out exhibition in various Walworth locations, South London. This was part of a student project with Artists Studio Company, November 2017). Photo: Glenn Michael Harper