The first ever MA Fashion Communication public exhibition is showing at the Lethaby Gallery from 29 November to 4 December. The Class of 22 reveal a cross-section of fashion at a time of unprecedented disruption - reflecting the new mood post-pandemic, amid climate and economic collapse, political warfare, contested equalities and social discontent – as well as what it means it means to work in this global and hyper-connected industry.

Responding to four major themes - Embodying Experience, Representing Communities, Talking Futures and Confronting Fashion - introducing some of the photographers, stylists, writers and journalists across 3 interconnected course pathways, whose gaze is firmly fixed on fashion - in all its finery and its flaws.

MA Fashion Communication: Image

MA Fashion Communication: Fashion Journalism

MA Fashion Communication: Histories and Theories

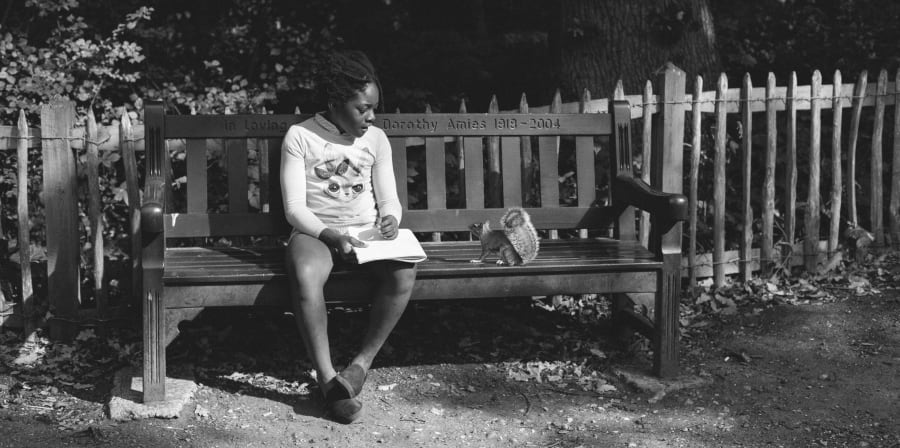

Diamond Abdulrahim, @d1md

MA Fashion Communication: Histories and Theories

Diamond Abdulrahim is an award-winning strategist, writer and creative consultant. Working across advertising, branded content, film and arts programming with expertise in fashion, luxury and its intersections across contemporary youth culture.

Your dissertation highlights the many neighbourhood contributors at the margins of the fashion industry - the cobblers, the alterations services and garment repair people. What can we gain by bringing their lesser-acknowledged skills and voices into the fashion dialogue?

"What we gain is a richer and more nuanced idea of what contemporary fashion work can be. It's a core question that I explore because of the many different ways you can situate their type of work; they are part of a service economy, it's a trade but we never consider the skills, both cognitive and creative, that allow them to do their job. I think this is closely related to our disconnection to our own worn or imperfect clothes that need to be cleaned or repaired in some way. And as conversations on sustainability in fashion mature, repair will have an even bigger role to play. But as brands and retailers are quickly offering these same services, the future for these independent shops on our high-streets is concerning.

I went into this project wanting to honour and elevate the work of those businesses in my local area. All of the research participants I got to spend time with at their place of work are first or second generation immigrants involved in a family business.

I hope that this research encourages us to interrogate the often racialised dynamic of service work particularly in London but to similarly recognise the spaces of autonomy and entrepreneurialism of those involved in this line of work.

A new module on the MA Fashion Communication course this year, ‘Reimagining Fashion Histories’ was inspiring in developing my idea to study these shops on my doorstep and to see it as part of the genealogy of decolonial approaches to studying fashion."

You work as a global fashion strategist and creative consultant. What are some of the key themes and challenges fashion brands need help with at this moment?

In my work I think the words ‘connect to culture’ feature in every project brief or client conversation I’m involved in, the definition of culture wildly changing depending on what brand it is. This can be from understanding fashion resale markets, the culture of archive collecting or to figuring out what tangible steps a company can take to becoming more purpose led.

I think every brand is trying to understand the value that they can add to society beyond their material products and services but for fashion it becomes an even more pressing demand.

How would you sum up fashion's mood right now?

"Fashion from an academic research perspective, I think, is in an exciting place that is constantly challenging its own biases, limitations and forgotten voices. Fashion on an industry level I’d say is a lot more complacent. I think it really needs more people who can challenge how it operates from the inside out. People that perhaps haven’t inherited the same romanticised ideals about it and can offer different perspectives, whether that's in professional backgrounds, lived experiences or areas of specialism.

I’m lucky to be a part of the pilot of The Outsiders Perspective programme and hope that by marrying my research experience and marketing background with new commercial knowledge it can go some way to building what the fashion industry of the future looks (and acts) like."

Kira Issar @kiraissar

MA Fashion Communication: Fashion Image

Kira Issar is a London based visual artist from Delhi, India, with a fine art aesthetic that punctuates the fashion photography form. Exploring the mingling of human and non-human nature, her work is led by eco-feminist theory and animal studies.

At the heart of Kira's work is a need to prise open power relations. Presenting an alternative, ecofeminist vision where there is no hierarchy between humans, the natural world and our nonhuman friends, Kira’s mind draws parallels between female and animal bodies, who become instrumental objects under a patriarchal gaze.

Kira presents ‘Medusa’s Prologue’: a bound book of black and white photography shot between London and Delhi that captures organic, physical shapes in female and animal forms: equal subjects that occupy domestic and public settings. Her fashion image portfolio invites us to see the body of the wearer as co-habiting with the garments and their immediate environment, while naturally rooted to the earth we all inhabit.

"Each image is personal as well as political. In my work, I make what I don't see in the world."

You make work that shows "what you don't see in the world": can you tell us more about this?

"I often witness people fail to make a connection between various anti-oppression movements. As I mentioned, all oppressions are interconnected, and they overlap, uphold, and reinforce one another.

How are racism, casteism, feminism, ableism, heterosexism, speciesism, capitalism intertwined? I don't see artists have a total-liberation approach to their work, and it's what I keep in mine.

For example, most feminists are ignorant of how animal liberation relates to women's liberation. The basic building blocks of any feminism is consent culture, bodily autonomy, an ethic of care, and the proclamation that the personal is political. Feminists betray their politics when they partake in the consumption of animals’ bodies."

How does 'Medusa's Prologue' connect with contemporary issues in fashion?

"Medusa’s Prologue is meant to be a debut of my female gaze, and an alternate depiction of bodies to counter the conventional ways women have been imaged. In Medusa’s prologue, I gesture at how other animals for the human species are consumed not only as objects but also as symbols.

I bring up other animals' bodies and nature in my work because my intention is to confront the fashion industry about the bodies it gets away with commodifying for profit - as shoes, bags, coats, jackets, props, or decor. It’s going to be a long conversation, but it's worth having."

-

Photo by Kira Issar

-

Photo by Kira Issar

-

Photo by Kira Issar

Raajadharshini Kalaivanan Krishnamurthy @mean_kaari

MA Fashion Communication: Image

Tamil-born Raajadharshini is a London based image maker whose style revolves around treading a line artfully, between documentary, fashion and portraiture.

How would you describe your photography?

“I focus my practice on exploring fashion as a zeitgeist by capturing a variety of raw emotions, real people, communities and human connection. I want to create work that challenges mainstream representation in fashion - where fashion doesn’t seem very alienating to people."

You make images that challenge traditional ways of representing fashion. Is there room in fashion for more personal stories and everyday cultures and aesthetics?

What exactly is fashion? It is not something that will only comfort white, rich, Western people and displayed on storefronts and billboards. It is yours and mine. It's everybody's.

"Fashion like culture continually undergoes change. As fashion plays a vital part in capturing the zeitgeist of the era we live in, I definitely believe that there is room for representing everyday culture - For everyone to see themselves represented in the mainstream visual culture. As Image makers like me who act as cultural intermediaries in fashion, we almost have a moral obligation to challenge this industry which looks very inaccessible."

Can you share the background to your exhibition project?

“In terms of fashion imagery, showcasing South Asia is still a small niche that barely has any authentic light to it. My photobook “Koothu” celebrates my background - the people of Tamil Nadu, their lifestyle, clothing, and culture in an effort anchor my community in contemporary visual culture and fashion imagery. Frames of real houses and real people in Tamil Nadu that oscillate between youth, joy, leisure, and inner conflicts of characters placed against the vibrancy and chaos of the State.”

How would you sum up fashion right now?

"Without question you cannot ignore the climate toll, labour crisis, fashion education fee, gatekeeping in the industry, and so on. But I think the young people are challenging the industry with their limitless creativity to make fashion more inclusive, ethical, actually sustainable by solving problems and creating for the future. We still have a long way to go but this constant evolution makes me hopeful.”

-

Photo: Raajadharshini

-

Photo: Raajadharshini

-

Photo: Raajadharshini

Pablo Roa Escobar, @pabloroa

MA Fashion Communication: Journalism

Born and raised in Mexico city, Pablo Roa, specialises in journalism with particular interest in the arts, fashion, crime, culture, and editorial industries.

Your MA research explores the gay legacy of men's mainstream fashion magazines. How does this influence you as a fashion journalist?

"This research was definitely a moment of catharsis. It became a strange self-help guide: something that had been a huge part of my life, but I'd never really questioned. I think it challenged me, yet again, to be conscious of who I'm reading, where it's published, why it's being written. Who owns this magazine? What is its history? All of these factors influence the words printed. Learning about this legacy made me feel less alone, and even more proud to belong.

I'd always felt embarrassed for thinking men's fashion magazines were a bit gay, but they are, and there's a reason for it. Growing up, one of my favourite things to do was go to bookstores and look at magazines. They were my first window into a different world and offered me a glimpse of things that were yet to come. There is a distinct way going forward with my writing. Perhaps more critical and observant, but at the very least, more liberated."

You challenge the term 'sissies' in your poster and text for the exhibition. Can you tell us about the story behind this?

"To me, it's about reappropriating the appropriation. Reappropriating the insult. When I profiled Runze, a young fashion designer from China studying at Central Saint Martins, there was a strong language barrier. But the meaning behind her work was fascinating. She spoke about how men in her home country go to ridiculous lengths to accentuate their masculinity and hide any trace of femininity. But she wants them to be aware of how absurd, and even comical, this can be. In China, the “face” is the front of the body, and it also represents one's dignity. If a man is humiliated, if he is denied from his masculinity, he loses his “face”. To express men’s hidden realities, she combines the most masculine twill or denim with the most feminine lace: creating men’s clothes transformed from women’s clothes. With her work, she proves that femininity cannot be masked.

Runze wasn't afraid to use the term "sissy", which I loved. “I admire people who dare to be sissies in China. Being a sissy in China requires more social pressure, compared to Western countries. They may be laughed at, humiliated, and abused by their family members or denied by others. In such a difficult environment, they still have the courage to be themselves, so I think they are brave,” she told me."

How would you sum up fashion right now?

Confusing. Yes, fashion is ever-changing and constantly transforming. But I believe now, like many other times, is a moment of passage.

"Thinking of big names: Tom Ford selling his beauty brand for billions, Alessandro Michele leaving Gucci, Raf Simons closing his own label, Demna Gvasalia in trouble after that Balenciaga mess... I don't know. I think the same boring answer always comes from this. "We need to change the industry" or "We need to make it a better place". And while that's true, what are you actually doing to achieve this? They cannot be just words.

However, I don't think we need to rethink the entire system as some people say: there are beautiful traditions to be kept. But at least let this moment of apparent change be one to self-examine. To question. To challenge. To demand. To be informed and make informed decisions. To make this world a more beautiful one."

Kanika Talwar @kanikatalwar

MA Fashion Communication: Journalism

Kanika Talwar is a fashion editorial writer specialising in fashion, lifestyle, travel, culture, entertainment, interviews, profiles and op-eds. Her work can be found in VMagazine, PopSugar, Fashionista, PAPER Magazine, Daily Front Row and more.

Your research explores fashion criticism in the digital age. Is there still a role for traditional media—and how have traditional media adapted as communication continues to evolve online?

There will always be a role for traditional media—however, it’s a matter of how many of those roles still exist as how people consume fashion criticism becomes increasingly digitised.

"Many fashion critics such as Vanessa Friedman, Cathay Horyn, and Robin Givhan have evolved and stayed at the forefront. Robin Givhan is formidable with witty, easily digestible writing about fashion as timely cultural criticism. She is still the only Pulitzer Prize winner ever awarded to a fashion writer in the history of awarding writers. I can’t ever see a time when fashion critics will become extinct. There will always be people interested in fashion, especially in general interest publications such as The New York Times, The Washington Post, The Wall Street Journal, and The New Yorker—whether on the business side of it or looking at the latest news on fashion and how it's evolving with the times. While the world has become digitised, people are very much craving to read great writing in fashion."

You regularly speak to emerging designers in your work for global fashion publications. What is important to you in telling their stories?

"Everyone and anyone can talk about Christian Dior, Fendi, Yves Saint Laurent, and more. I do write about them as well, but they will sell no matter who is the creative director/head of their brands. They don’t need more press—younger and emerging talents don’t have any real funds to get their name out there. The industry is extremely tough as it is. If I can use my writing skills and publication connections to spotlight designers who deserve to be recognised and are doing interesting things, then I will do so.

For me, it’s always been about connecting with people and getting to know them, their stories, and who they are. I’ve attended shows at Central Saint Martins, London College of Fashion and more. It’s a great feeling to see that many young designers I feature in my projects later end up getting further press coverage."

How would you sum up the fashion mood right now?

"The fashion industry is going through a weird transition as a whole. As an industry, it has become part of the larger pop culture phenomenon. Especially during the pandemic, fashion has become more visible and in your face than ever. And in doing so, the industry has been opened up to a large variety of people who maybe never had the chance to be part of the industry. But, it has also opened the industry up to people who aren’t tied to the industry falling and rising—people who don’t care about the industry doing better as a whole.

The industry has to decide whether it's going to continue to stay a niche, craftsman-oriented industry or become part of the larger cultural aspects of life. And on the flip side, if that happens, fashion has to stop being treated by the general public as a frivolous, trivial, and shallow industry. There are billions of dollars and countless people whose livelihoods are tied to the industry. Frankly, it’s completely sexist that the only industry dominated by women for women is written off entirely.

Fashion obviously has been one of the biggest targets when looking at the aftermath of COVID-19 retailers closing and the economic recession. But at the end of the day, fashion will endure—it has continued through multiple world wars and it will survive the current turmoil we are living in."

There’s a sense of transition in the air.

"The most recent news of Tom Ford selling his brand to Estée Lauder, Raf Simons shutting his brand, and Alessandro Michele stepping down from Gucci are all sad but hardly surprising news. People have been asking for new blood to come in and end the tiresome musical chairs, and that’s what it looks like will happen soon. The industry needs more designers who know when it’s time to hang up their gloves.”