A 2017 study found the number of LGBTQ+ venues in London had declined 58% in a decade. Here, we talk to graduating students presenting new manifestations of queer space.

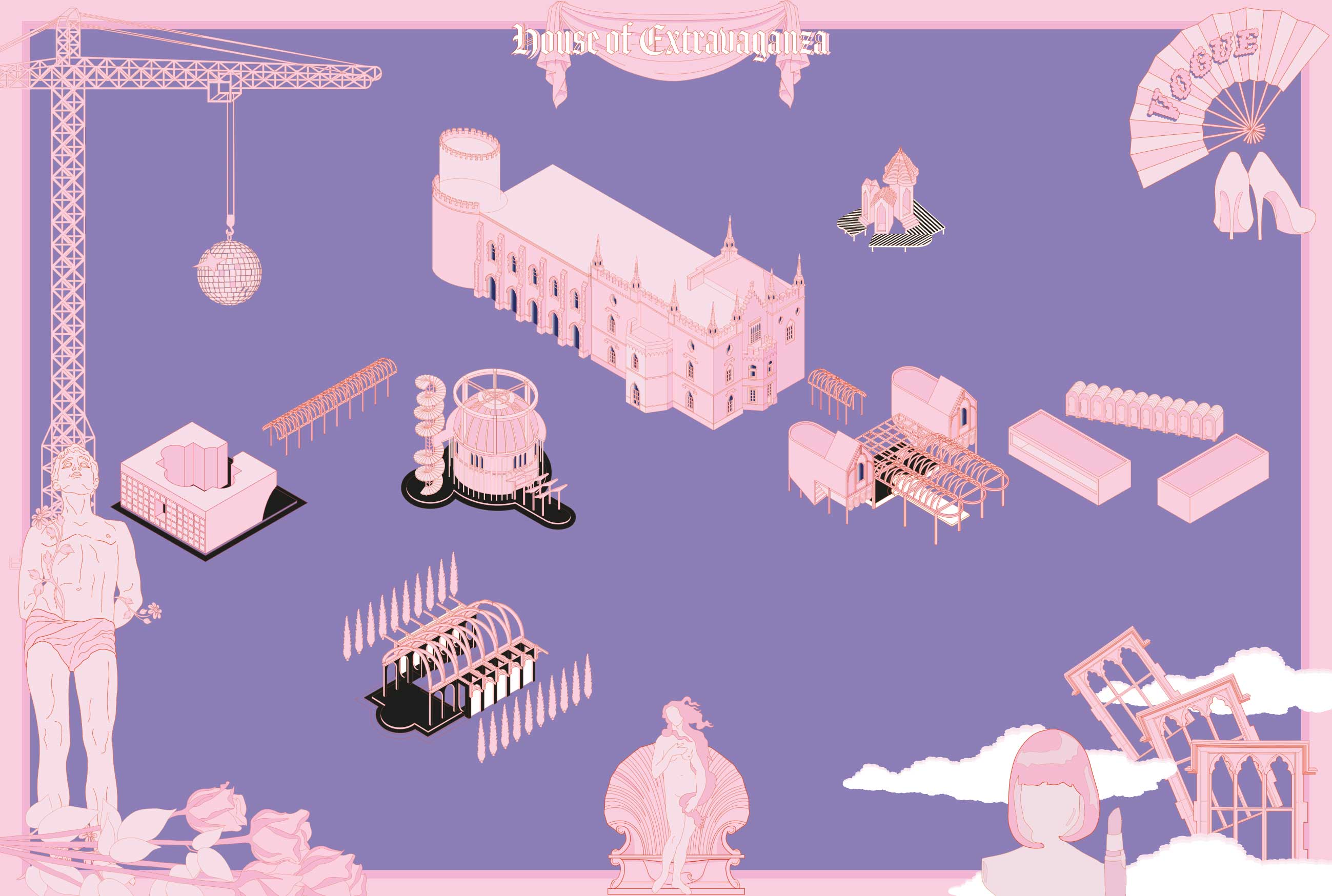

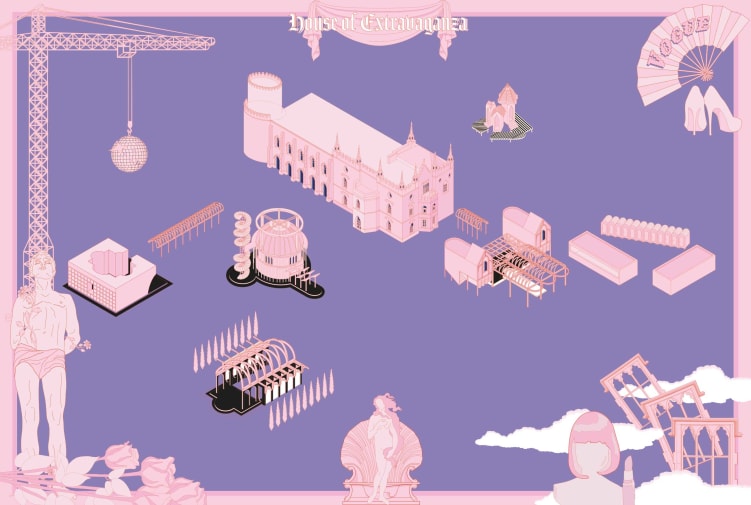

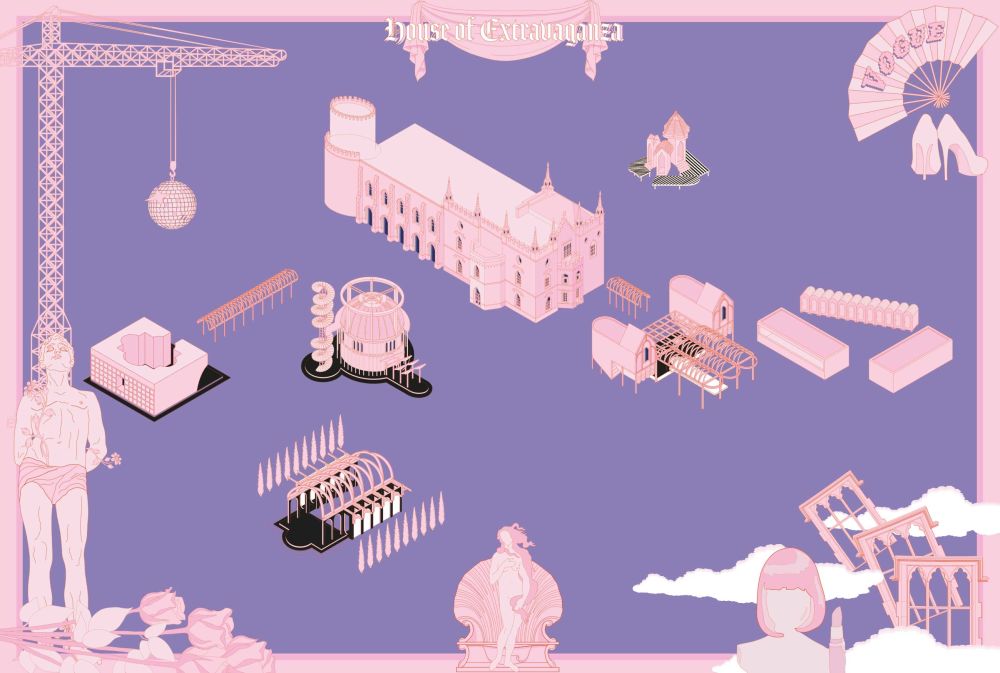

For Kleanthis Kyriakou, M ARCH: Architecture, the future of queer space begins in the past. His project, House of Extravaganza, takes Strawberry Hill House, an 18th century Neo-Gothic villa built by Horace Walpole as its starting point. Recent research has reframed the house as “queer gothic”, a protected space for the personal expression of its patron:

“One of the reasons I moved to London was because I want to be who I am freely, and unapologetically… London became a haven, a sanctuary in which I could perform my identity. When I discovered Horace Walpole, I was fascinated. Three hundred years ago he built this mansion as a place for him to perform his identity.”

In Kyriakou’s hands, Strawberry Hill is transformed from “a place of protection to a place of projection”. The House of Extravaganza launches with a memorial for London’s lost queer spaces and then opens its doors as the city’s first queer palace, a site for events and interventions but also an incubator of other queer spaces across London.

Kyriakou combines the gothic visual style with gay bath houses, pleasure gardens, cruising parks and drag stages. His project reflects a cis-gendered male experience. “I had never thought I could pursue a project that dealt with queer space or minorities’ claim to space,” he says, “I never thought my work could be so personal because we always hear that architecture is for ‘people’… We want to be so inclusive that sometimes we forget that we have to exclude to include.”

The project celebrates the fluidity of identity through the impermanence of events themselves and the palace’s liminal position at the edge of the city. Created primarily for its queer community, The House of Extravaganza welcomes a non-queer audience for public festivals, as Kyriakou explains, “if you can experience queerness then you can understand it."

Exploring the breadth of queer space, Lucy Hayhoe, MA Narrative Environments, brought together artists, performers and writers for her exhibition Queer(ing) Space. The loss of LGBTQ+ venues in London, combined with curiosity at her own changing experience, inspired her to explore existing spaces and what makes them open to the queer community:

“There are obvious things like flags, toilet configuration and gender-neutral facilities, but also recurring adjacent factors like proximity to cultural institutions, population diversity and the wider urban context. All of these elements add up to why that community happens to be in a gay bar in the middle of Soho and not in a country pub in a village. You see the ripples that make the conditions for clusters of queer spaces. But that doesn’t answer the question 'what is a queer space'. To answer that question you would have to have a clear definition of ‘queer’ and a definition of ‘space’ which are two very fluctuating and contested concepts."

Queer(ing) Space gathered together work by artists, performers and writers as well as asking the audience to map out their own experiences in the city. Hayhoe created an installation for the show titled One in, One out: Deptford’s Smallest Gay Bar. The bar is only large enough for one, a reminder of the reduction of actual LGBTQ+ spaces but also a spatial experiment itself.

“Commercial gay bars are often thought of as spaces for white cis-males with pop music and glitter balls. I feel quite conflicted about these spaces because, while I can still enjoy that environment, I don't understand it as my space or as a queer space necessarily. In these spaces I can appreciate the break from heteronormativity while still feeling out of place.”

Hayhoe’s truly tiny bar is defined by the person inside it: “I think the assumption is that you go to gay bars to meet people for some kind of relationship, but being queer isn’t always about your relationship to another person – being on your own on the dance floor, there is a loneliness but also a pride in that. In One in, One out, you can do whatever you want you’re not there for anyone else."

One in, One out will be touring festivals in the future – it is, after all, a perfect socially-isolated bar – and Hayhoe sees Queer(ing) Space as the beginning of her exploration. But, what could queer space be in the future? “I think it would be really exciting to think about queer space in myriad forms that don’t always happen in city centres, that don’t have to involve alcohol, that don’t prioritise cis gay men so often… In lockdown there’s been a lot of queer house parties that have moved online, queer sober spaces, QTIPOC groups, writing groups, support networks. Perhaps we are expanding ideas of what a queer space can be. When we move beyond this current coronavirus situation it’ll be really interesting to see how and if these digital spaces physically manifest.”

Questions of queer space are not defined to spatial disciplines only, Furmaan Ahmed, (BA Fine Art), makes temporary work as sites for events and community celebration. Their practice began in a more private context: “It came from me being in this exact same room,” Ahmed says speaking from their childhood bedroom, “I needed a place to live and be myself. I grew up in a Pakistani community, it’s quite religious and conservative so I was creating self-portraits using Tumblr as an exhibition space. Those images became quite extravagant as time went on. I would make one every few months and I would transform the space around me… I’m still making those worlds but it’s not for me to be in, it’s for the community.”

Ahmed’s practice grew into set design and art direction, creating work at Tate Modern, Jupiter Artland and Edinburgh Arts Festival: “I’m really interested in emotional sites of knowledge. It can appear anywhere: a space or a group zoom meeting – the centre is connectivity not the way it looks.”

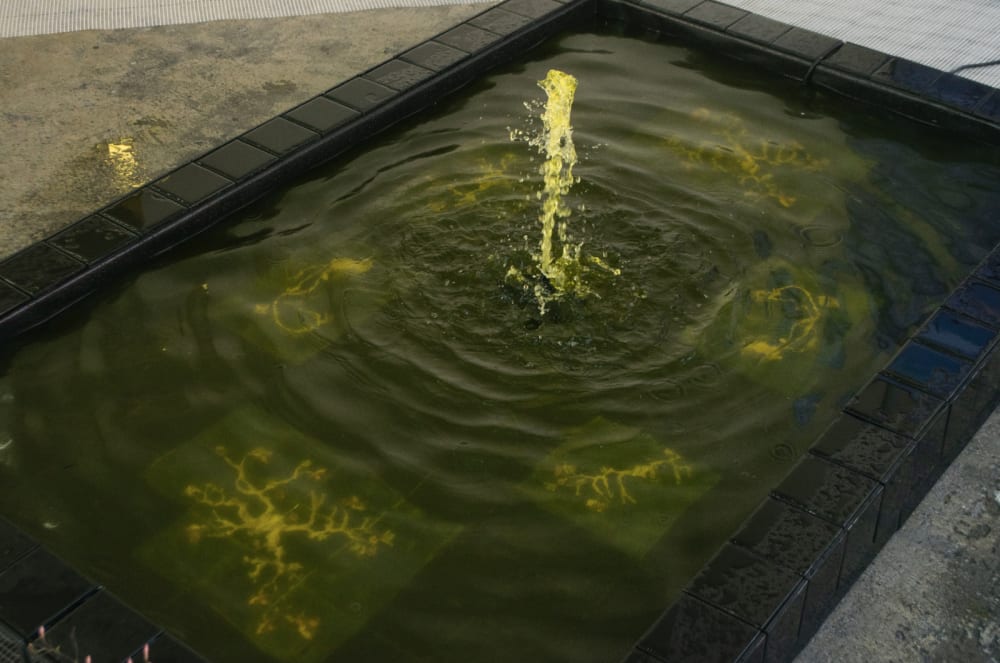

For their final project Ahmed proposed a garden, installed within Central Saint Martins, the setting for a week-long festival with workshops and performance spanning mandala art making to queer combat training. The programming expresses Ahmed’s emphasis on radical self-care for the queer community. The structure, an austere fountain, was to be graffiti’d with the names of queer and trans people murdered in 2019. Visitors would be invited to scratch their own names into the structure as an act of solidarity.

“I want to facilitate experiences about learning and growing together, new structures of working as a community. The main focus is joy, celebration and radical love. That sounds so hippy, but it’s responding to our culture in the UK to not show affectation… my work isn’t going to change policy directly, but it can elevate mood and create a connection and that makes fighting for change so much easier.”

Kleanthis Kyriakou is nominated for this year's MullenLowe NOVA Awards and won a Spatial Cultural Equity Award. Explore the full list of nominees.

More:

-

Leo Nataf and Tom Lellouche

-

Grizedale Arts - Information kiosk and a community bread oven (Credit: Takeshi Hayatsu)

-

'Dyskopje' - Skopje Field Trip project