For Show Two: Design, we connect the dots on students presenting their work to the public for the first time.

Kevin Germanier’s BA Fashion collection looks as far from waste as it’s possible to get. “I want people to smile,” he says of these explosions of colour, light and transparency, gowns giving glamour with a delicacy.

His interest in re-using waste material came from an ethical stance but also a practical one. “I don’t want to go to a shop and buy fabric because I always feel so guilty,” he says, “but also, it’s about the challenge to create incredible work without much money.”

Having won the EcoChic Award, the designer was on a 3-month placement in Hong Kong during his degree. One day he discovered a man sheepishly discarding broken beads into a pit in the ground. “They cannot be sold. Why? because they are broken, the package is open or they’re the wrong Pantone colour? I was so shocked about the waste.”

Germanier experimented with possible uses for the rejected beads and alighted on a silicone base as a way to combine them into his designs. Both strong and soft, the base is set with beads and the resulting panels are used to construct the garment, their weight and pliability exploited to hang a particular way upon the body.

“I want the audience to think it looks more couture than sustainable. I want to show that you can create sustainable fashion without making a linen shirt!”

Kevin Germanier

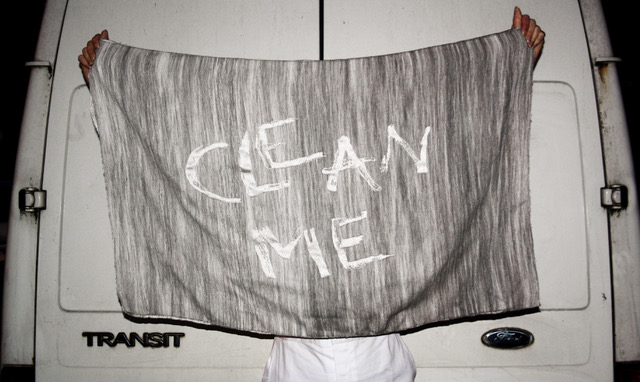

In a different way, material exploration is at the heart of Helen Milne’s series of protest flags and textiles. “I’m using textiles as a communicative message, flags are very important, we are living in a politically-charged time.”

In Archiving the Anthropocene, the BA Textile Design student responds to climate change not only with slogan but also with the fabric itself. Her Air Pollution series, with a centrepiece flag exclaiming “Clean Me”, includes white yarns darkened as they were rubbed on white vans and stuffed up exhaust pipes, embedding them with grey particles of pollution. The Coastal Erosion collection, inspired by a trip to Dawlish, combines copper wire with paper yarns. In a combination of sateen and satin, the resulting fabric was treated with vinegar, so as the metal corrodes it dyes the nearby threads creating a constantly changing textile landscape.

Archiving the Anthropocene is performative, meant to inspire declaration and action. Yet with her material comes an undeniable aesthetic beauty:

“I’ve had people say that it’s too beautiful. I like it too much. It’s not nasty enough. But, as someone in a design discipline, my work has to be enticing to provoke thought, otherwise there’s no engagement”

Helen Milne

It’s not only material that gets overlooked and discarded. Nick Woodford, graduating from MA Architecture, has alighted on a series of wasted spaces in his local area in south London and, through a process of conversations and collaborations, is repurposing them into The Peckham Coal Line.

Interested in spaces with the potential to be something more, realised that using a bit of imagination, you could connect Queens Road and Rye Lane with a 900m linear park. “It opens up a whole bunch of larger spaces, old coal drops, stable yards, disused bits of truncated road and cul-de-sacs,” says Woodford, “all of these things by themselves are non-places, places for dumping and parking but suddenly they get connected and become a whole lot more useful.”

Setting up a website, drumming up support and crowdfunding, Woodford and a team of collaborators, began to turn this initial idea into a reality. Through the donations of nearly a thousand people, the initiative raised £75,000 for a feasibility study.

Bidwell Street is the first of The Peckham Coal Line’s spaces, a short piece of road, used mostly for fly-tipping. Throughout 2016, Woodford ran a series of events – from wassails to tea parties – to bring life the space. Planters were built, murals painted and mosaics made and with each intervention a connection forged between place and people.

It is this connection that is at the centre of the project:

“In a place like Peckham, lots of different people live in a small space but often don’t cross paths. Shared spaces are our common interest. We don’t feel that we have much agency but together we do, we have a collective power. If you can come together with other people and negotiate, then hopefully you can make something that works for everyone.”

Nick Woodford

The development of the Peckham Coal Line doesn’t simply make something where there was nothing, it reduces council costs as spaces transform from liability to community asset. “We see value beyond the economic, that’s a big part of it,” explains, “these places are neglected because often they don’t have a perceived economic value.”

The Peckham Coal Line won best community project at this year’s London Planning Awards, but is not the only project of its kind with community-led schemes springing up across the UK. Woodford has setup a cooperative collective, Mesh Workshop, which as well as steering the Peckham project is part of the Mayor of London’s Special Assistant Team engaging in various transformation schemes around the capital.

The closing collection of this year’s BA Fashion Show began with a model pulling a structure built from old windows. Throughout the presentation of the collection, things were added to the platform, until the final model carried another window down the runway to complete the collective piece, leaving it on the runway, a remnant.

“A window for me is symbolic. I’ve always loved them. They’re a lens to another place.”

Matthew Needham

That place, for Matthew Needham, is a future where man’s effect on the climate means humanity harnesses its ingenuity and makes what it needs from the detritus of its doomed consumption. All of Needham’s clothes are made from found fabrics, fly-tipped waste and retailers’ dead stock.

A combination of a year spent in industry and trips to Norway made Needham confront the wastefulness inherent in cycles of production and consumption. “It’s changed the way I think about the world,” he says.

Since then, the British Fashion Council scholar has been hoarding. There’s no other word for it. On his daily walk to College he would collect whatever sparked his interest, including unlikely things like peeled paint. Needham would even create his toiles from the discarded pieces found in the workshop. At the heart of the collection is not only an Anthropocene philosophy but also the practical challenge to a maker in a process that restricts resources and yet encourages ingenuity.

Needham’s clothes, full of urgency, offer insightful contradiction on what it is to be sustainable in fashion: both utopian and dystopian, a crafted future of seemingly impractical garments. Many of the projects in Show Two, exposed our contradictions and weaknesses when it comes to finding value in material. Beyond sustainability, these designers show how context and craft can reconnect us to things we had once discarded.

More information: