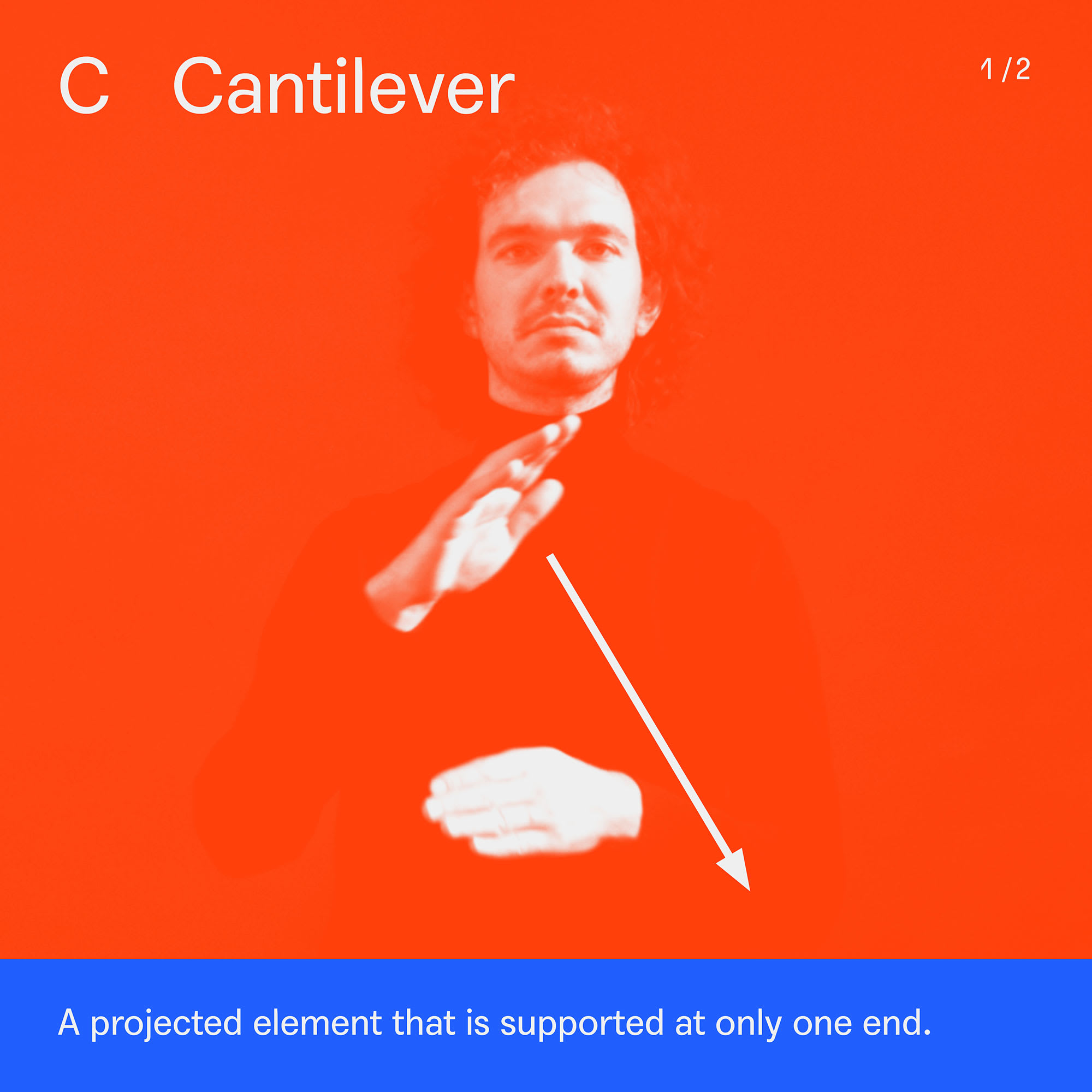

Signstrokes introduces standardised sign language for architecture. It is the result of a collaboration between Adolfs Kristapsons, who graduated from M ARCH: Architecture last year, and Chris Laing, Royal College of Art graduate. Here, Kristapsons tells the story of the project.

Deaf people are not new to architecture however they face significant barriers because the sign language vocabulary of the profession is not standardised and lacks terms to express architectural concepts uncommon in everyday language.

During my time as an architecture student – throughout part 1 and part 2 education – the constant need to find new signs to communicate the spatial nuances being discussed was challenging. Often, each individual Deaf person and their interpreting team create their own unique translation.

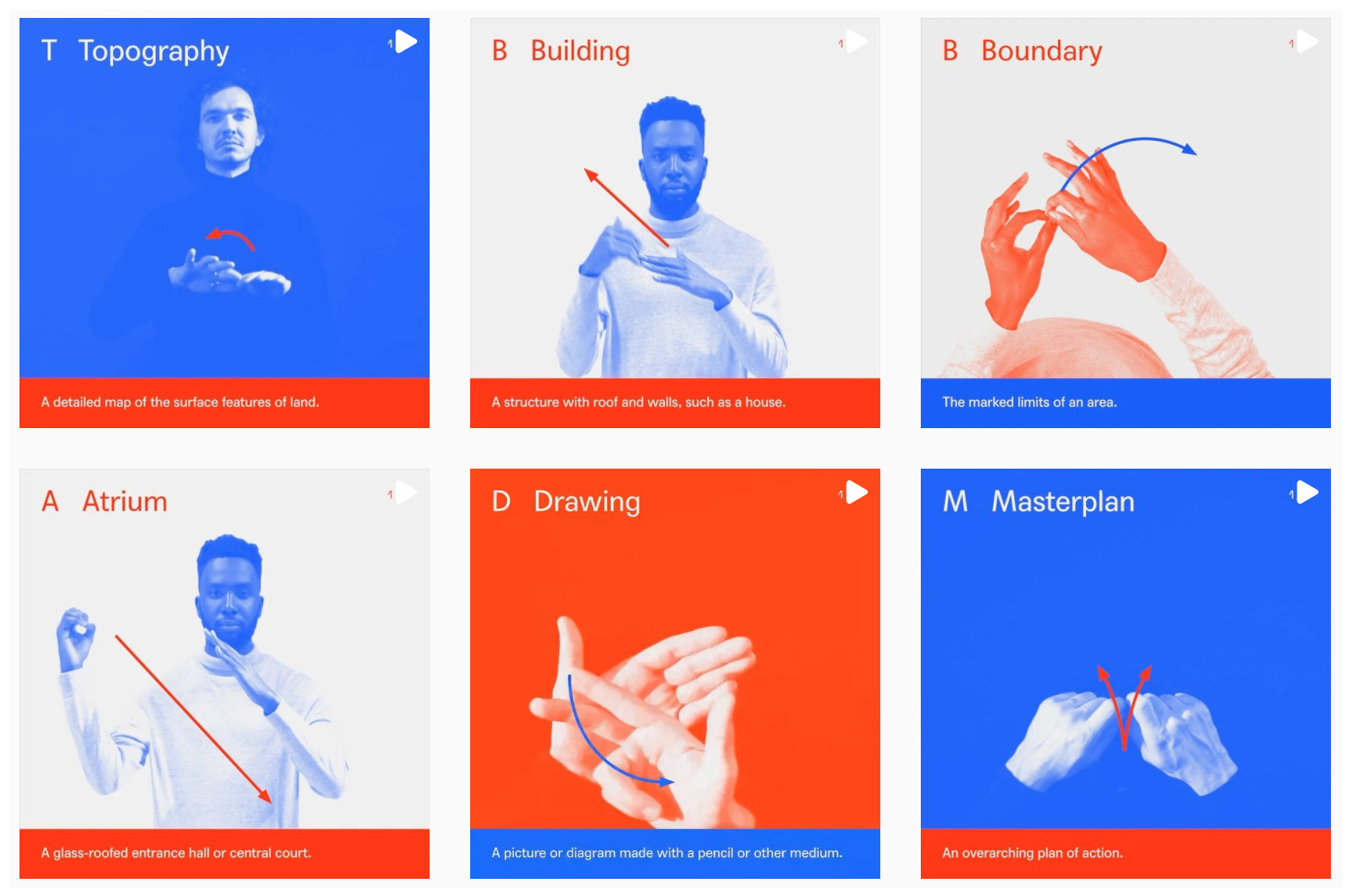

And so, Signstrokes was born; a linguistic project that breaks the repeated cycle of making new signs by finding common ones. Could we establish a set of root linguistic forms with logical rules that can evolve alongside the profession?

I have my own inherited sign language knowledge because I'm a fourth-generation Deaf person, and all the men in my family were builders. We have inherited our own building industry knowledge and found our own ways to communicate with each other.

In addition to the domain-specific context, we need to consider how context of individuals alters the way languages are expressed. British Sign Language (BSL) is native to Britain and not universal. Like all languages, it has developed organically and is influenced by environment and culture. There are also differences between users, the same as a spoken language which has regional differences in vocabulary and pronunciation.

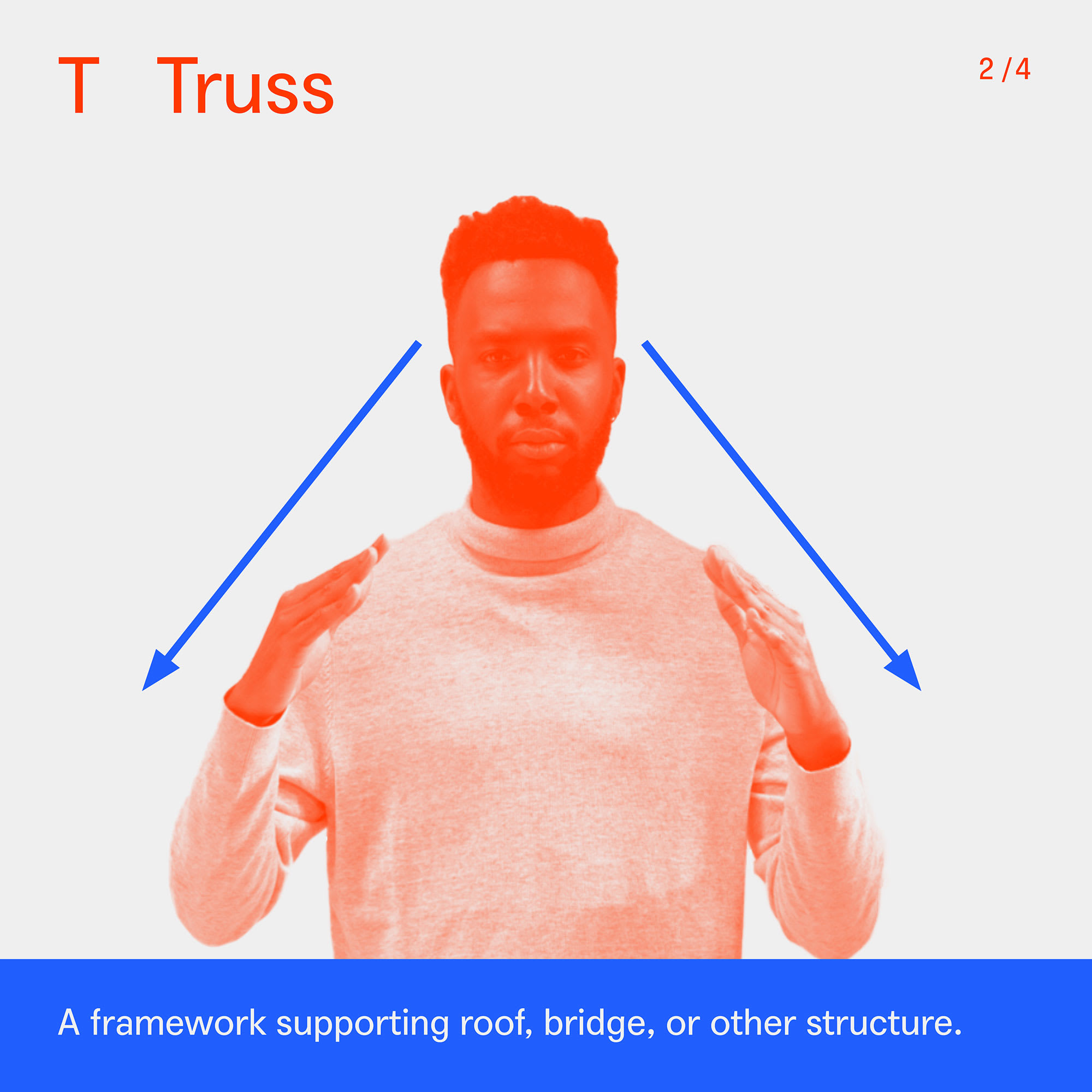

To create new signs, we needed to consider particular hand shapes and movements that are characteristic to BSL users, to ensure so that any new signs would fit seamlessly into the existing vocabulary.

That said, the growth of social media there has permitted more lexical borrowing from other sign languages which are then amalgamated into BSL. This borrowing is more common among the younger generations. For example, the sign for bamboo is borrowed from Chinese Sign Language and the sign for Notre Dame is from French Sign Language (many of these examples can be found in the @thefamilyvocab).

-

Architecture, Signstrokes

-

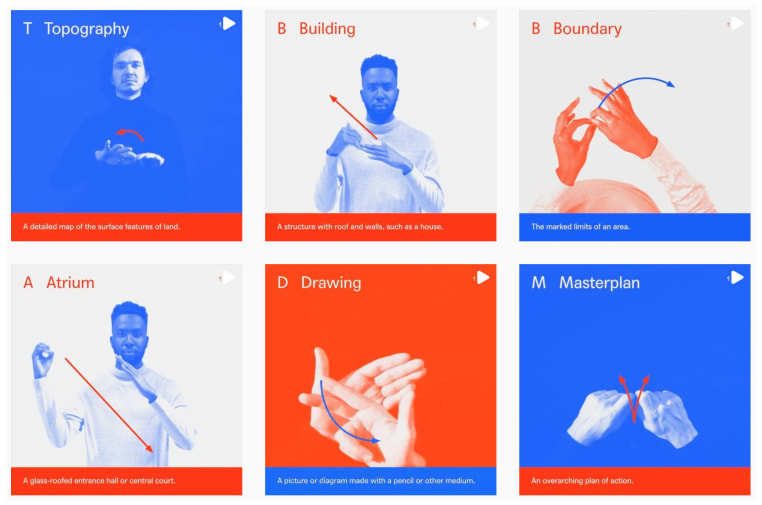

Cantilever, Signstrokes

Visual signs can often contain spoilers in their directness which is quite unique among languages. The signs themselves can be iconic meaning they are a visual representation of the word. The advantage to this is that the sign can be coded to include a lot of visual information which can be given very quickly. However, the disadvantage is that the visual information can become fixed in its meaning. As an example, the sign for “roof” shows a traditional pitched roof – but a roof, as we know, can come in many forms and doesn’t have to be pitched.

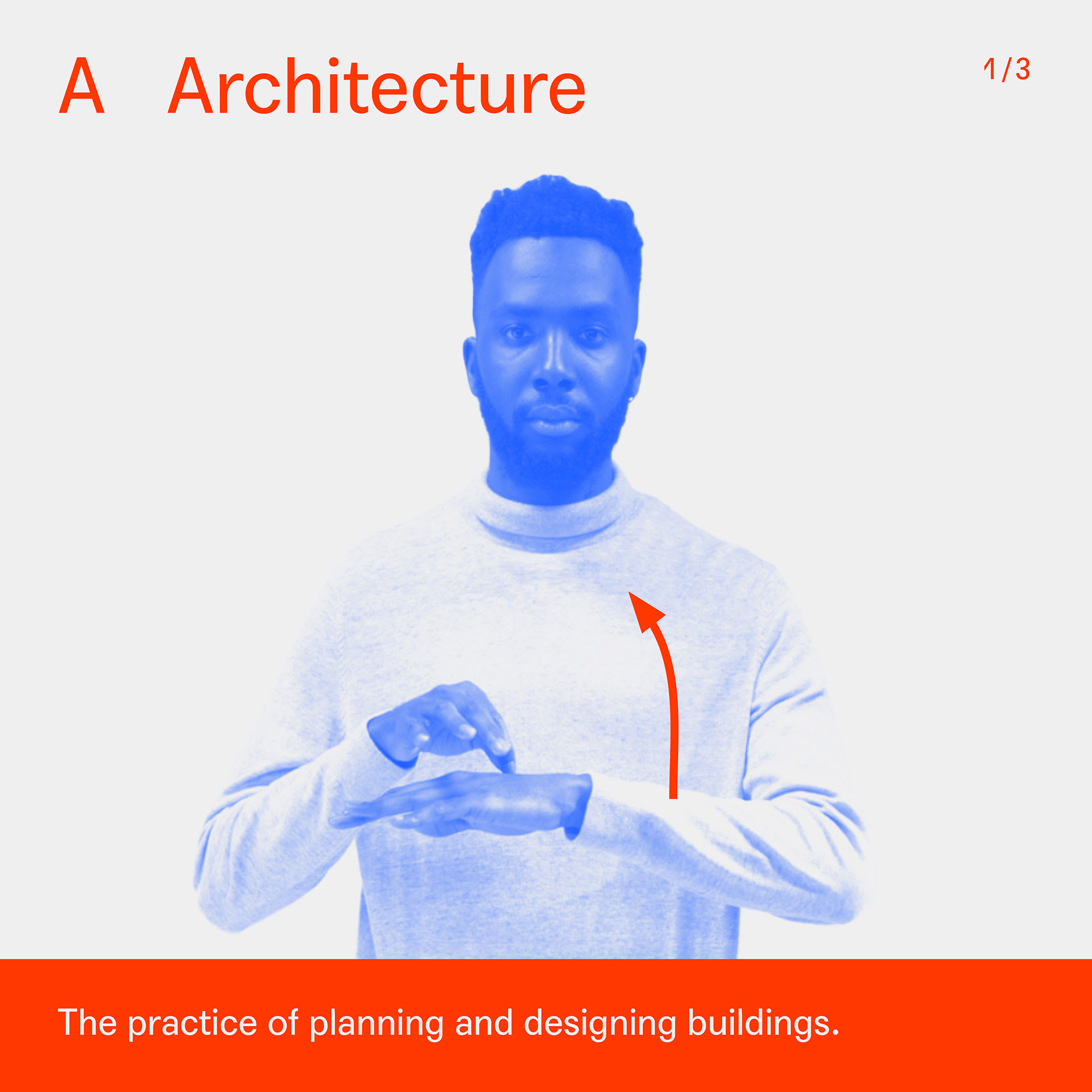

Chris and I ran workshops with other Deaf practitioners to evidence the lack of logic and consistency with current technical signs. With advice from Dr Kate Rowley from the UCL Deafness, Cognition and Language Research Centre, we explored what existing signs could be incorporated into this body of architecture-related sign language. As the collection of new signs began taking shape, we ensured that consistency and linguistic logic guided any further development.

We wanted to test our emerging vocabulary with children to unpack the highly technical language. We began a collaboration with Frank Barnes School, a local school for Deaf children formed with a truly bilingual philosophy.

-

Section, Signstrokes

-

Truss, Signstrokes

Due to the pandemic lockdown, we developed kits so the children could work on this project at home. The kit asked them to draw and build their dream home, which seemed to be a fitting theme for during the lockdown. It came with a BSL video of the homework instructions prepared by Chris and I, who used the new technical signs while remaining age appropriate and engaging. The children were asked to share their creations with each other. The intention was to test our signs, exchange knowledge and to build awareness for the children that the space around them is being constructed (by someone else’s dream!). Could a sign language resource serve as a tool for children to explore and develop their interest in a possible future career? Not just in architecture but many other professional fields.

With the collection of signs now available on our Instagram account, this linguistic exploration has value both to the Deaf community and to architecture as a practice. It can act as a gateway for students as well as established practitioners and has the capacity to grow as more Deaf people move into the field. We hope this project encourages architecture as a practice to include more diverse role models both in terms of culture and language.

Project Credits: Jayden Ali (Project Coordinator), Adolfs Kristapsons (Project Lead), Chris Laing (Project Lead), Sevinc Kisacik (Consultant), Milly Wood (Consultant), Dr Kate Rowley / DCAL (Consultant), Marcos Villalba (Graphic Designer), Martin Glover (Contributor), Haworth Tompkins (Knowledge Exchange Partner), UAL / CSM (Knowledge Exchange Partner), Frank Barnes School (Knowledge Exchange Partner).

Signstrokes is taking part in the London Festival of Architecture 2021 with workshops on the 25 and 28 June.

More:

-

Architecture, Signstrokes

-

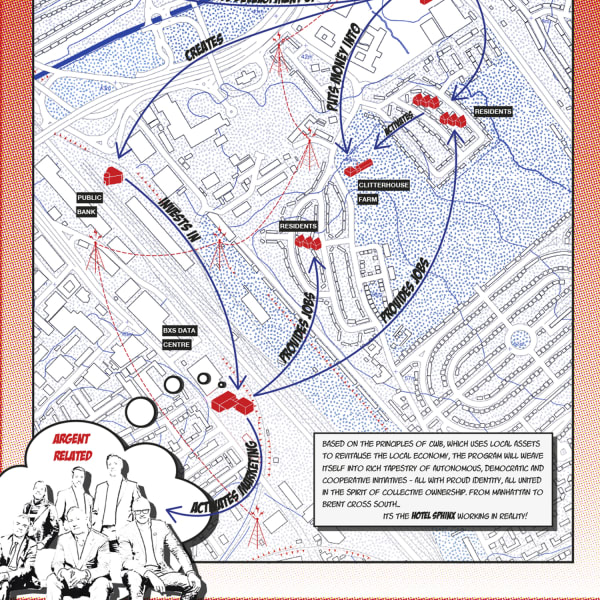

Lois Innes - Brent Cross South Cooperative (Credit: Lois Innes)