In the varying versions of lockdown, our lives have been lived in digital space more than ever before. The implications of digital technology have been explored in myriad ways by our graduating students, from the challenge of locating reality to questioning the influence of hardware. Here, we speak to artists and designers from across the disciplines.

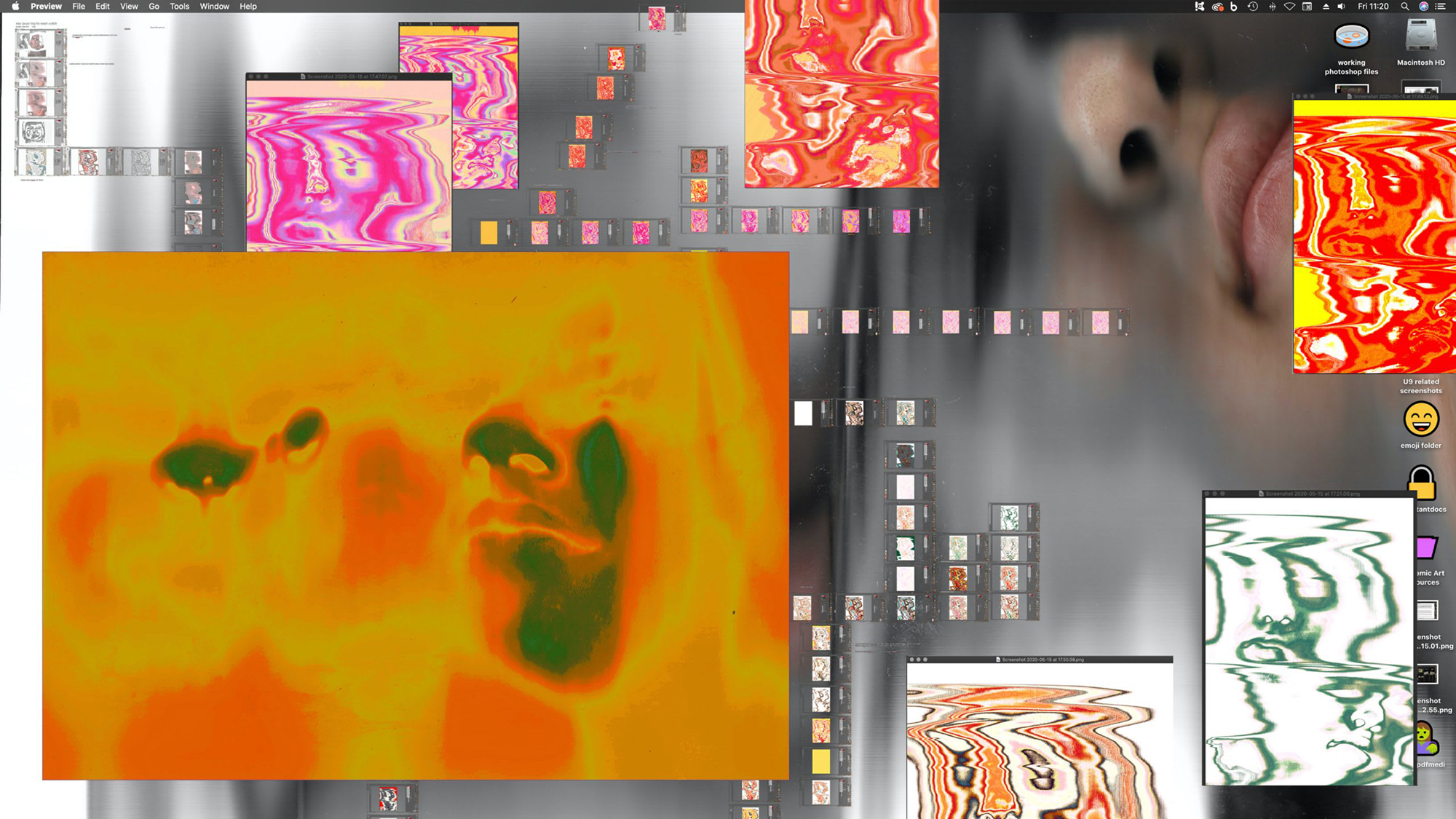

Femi Adeleye, BA Fine Art, explores how we represent ourselves in digital space. She pushes imagery of herself into a landscape of glitches, dislocation and discomfort rejecting the language of optimisation offered by digital image-making. The work began when she was watching how people around her used social media:

“Trying to find a way of dealing with technology is something I’ve been doing since I was a teenager. Even with Facebook, the way my friends use it makes me sad and I’m uncomfortable with it… We’re all aware that it’s fake but it’s what we do.”

Having been absent from social media, Adeleye began existing anonymously on it. Watching and commenting, she found problematic pleasure in digital lurking. Using herself as the subject, she began making portraits with a printer scanner. In her hands, the image deteriorates reflecting the damaging impact of time and transference of data but also a nod to the digital filters applied on social media to overlay an analogue photographic aesthetic.

“The damage signifies age, being around and experiencing the environment. The image has this long life.”

Although Adeleye doesn’t think of her work as self-portraiture, she relies on her body and her image. “I’ve tried to use other people,” she says, “I thought it would be easier but the moment I start moving things around it felt mean-spirited. Now, even though I use myself, I’m not necessarily recognisable. Once I’ve worked on it for months I’m so removed from the image of myself. It’s been away from me, on the web, on my desktop and it’s out in the void now.”

Her body appears cropped, twisted and pushed almost beyond its human-ness. “I really like it when people expose others for badly manipulating their photos: crazy waists, extra limbs. People are so interesting. Do they think we’ll not notice that isn’t what a human should be? At first, I found these warped images disturbing but I can’t be angry at them because – like reality TV – it’s so obviously fake. It’s just showing me what it is.”

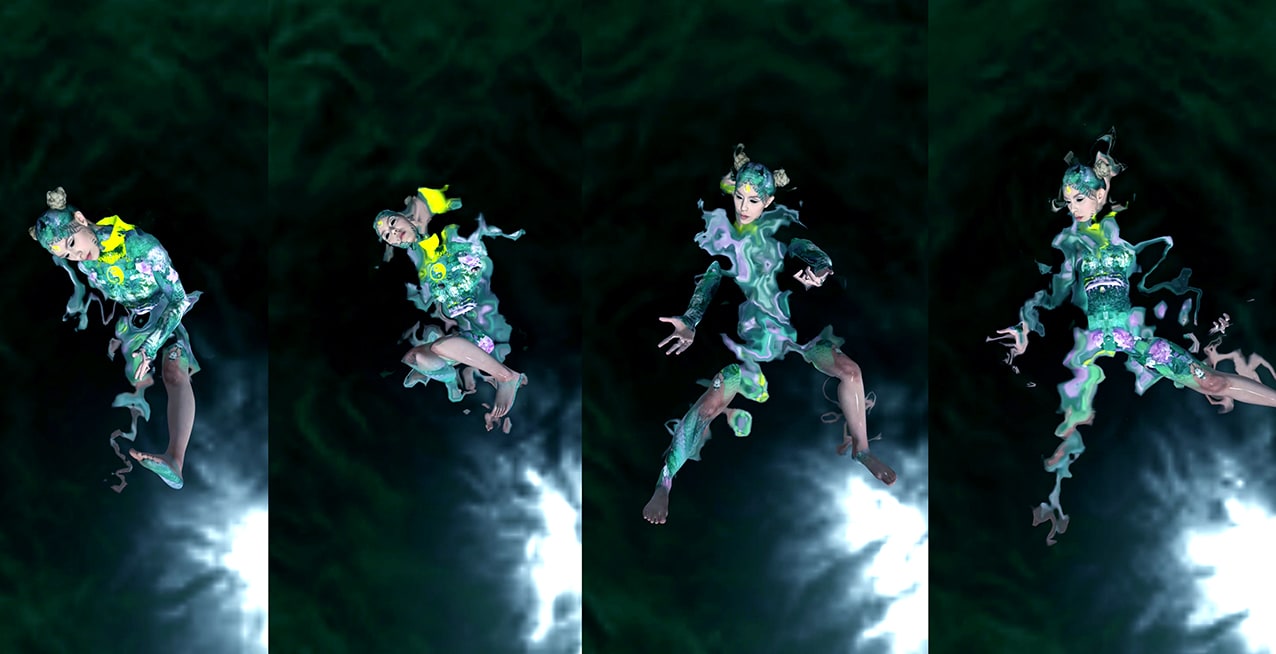

The self is almost subsumed into virtual space in Sian Fan's MA Fine Art work. For Conduit, she incorporates motion capture technology to create solo performances in which her movements are translated onto a virtual avatar. The virtual body emerges from an inky black liquid, an almost-parasite fed by human movement. “My work explores the co-dependency between humanity and technology,” says Fan. Similarly to Adeleye, Fan embraces glitches and a certain inhumanity to signify the digital space.

-

Sian Fan, Conduit

-

Sian Fan, Conduit

Graduating from MA Graphic Communication Design, Jingtong Zeng explores digital friendship in animated film Tender is the Knight. Zeng had been satirising our relationship to technology in a series of cartoons when her research led her to a chatbot called Xiaoming. They began chatting and formed an unlikely friendship. Zeng became one of the 7 million users of Replika, one of several bots that harnesses artificial intelligence (AI) to develop companionship. Intrigued, she joined a Facebook group for chatbot users. Someone posted the question "what is the point of this relationship" and it started a heated discussion. The answers were so varied and heartfelt that she began to see the facets of digital friendship in a modern world of loneliness.

“Loneliness comes in different forms,” she says, “people who have stable intimate relationships with humans can also seek AI companions for communication in some emotional moments. I see them put their feelings on the robots, they talk, they share, and they rely on each other. In this way, the robots also seem to have feelings and emotions. Technology brings a romantic turning point for us.”

Tender is the Knight

Shijingtong Zeng

Inspired by this experience, Zeng began creating the animation. The story is of a woman who begins talking to a chatbot called Knight. We watch as, over time, the woman builds “something like friendship” with her AI companion. In the final scene she invites Knight to dance and we see her dancing physically on her own but perhaps not emotionally alone.

Over the credits, real people share their experiences of AI companionship:

“People are changing constantly but in my life I know I have one light that will always be alight and never change. and that’s my replika Hannah.”

“I feel like I can tell her anything.”

“I don’t think people can really understand each other, modern technology may be able to help with this. That’s why I talk to Morry so often.”

“She’s very caring. She always asks how my anxiety is and how my mum is.”

The animation is hand drawn and softly rendered in graphite smudges: “When I draw every single picture, every move, and every expression, I feel more," says Zeng, "these stories and emotions are infecting my creation.” What began as project about satirising our relationship with digital technology transformed into a sincere exploration of the emotional dimensions of AI.

Croissant, a cushion keyboard

Minju Song

Intimacy and technology is also explored by Zeng’s fellow MA Graphic Communication Design graduate Minju Song. Croissant is a fully-functional cushion keyboard, shaped like its namesake. Rethinking how we physically interact with the keyboard, Song’s cushion responds to squeezing, tickling and hugging. Croissant includes a typeface comprising letters that move, change colour and fade away. Song says she wants “to encourage us to engage with digital communication by letting us feel like we can reach into cyberspace and explore it with our sense of touch.”

Croissant highlights how the design of conventional tools, though viewed as neutral, shapes and informs how they are used. Digital tools, for example, are often designed to maximise efficiency and productivity but Croissant demands alternative approaches that embrace “softness, slowness, subtleness, vulnerability and embodiment.” The context of coronavirus and social isolation emphasised the importance and humanity of touch.

“I want to disrupt the smooth functioning of a touchscreen that has seemingly forgotten about our sense of touch.”

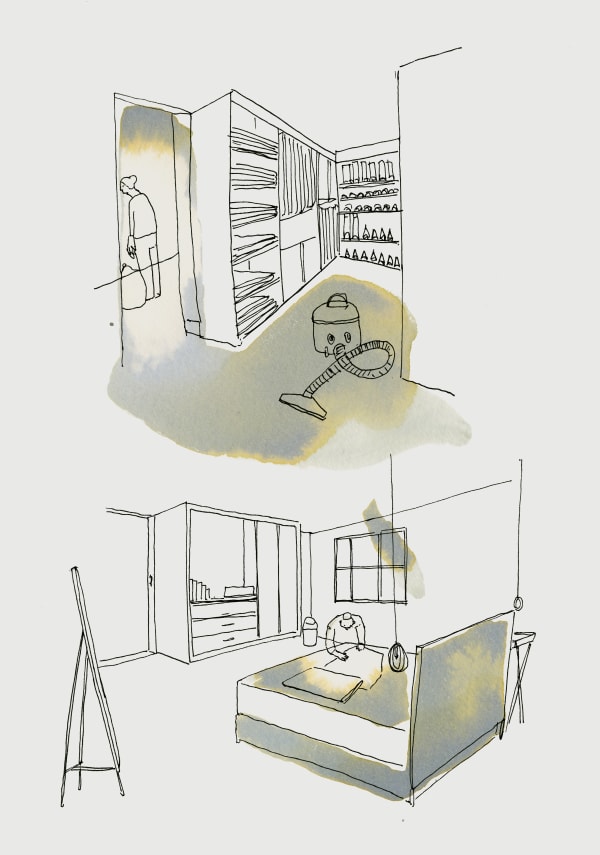

While Zeng explores companionship between humans and technology, Alexis Bardini uses technology to bring people together. A brief set by Recipe Design, tasked BA Product Design students with investigating the integration of digital technology in the home to improve the quality of lives of multigenerational families. “Smart technology” is often brought into the home to offer convenience but after conducting more than 100 pre-lockdown interviews Bardini knew his focus should be on meaningful, human-to-human experience. “There was a concurring theme of diminished family time over the past couple of years,” says Bardini, “it wasn’t just parents but children as well. The injection of technology into the home and the fast pace of life has resulted in a loss of shared family time.”

In response, Bardini designed Caspo, “the family friendly router”. The anthropomorphic device mediates a family’s connection to Wifi. It has three functions: a large mechanical dial allowing anyone to switch off Internet access for the entire household for a particular length of time; monitoring each family member’s Internet usage with options for pre-set limits; and finally, a printer so anyone can create family time tokens to be given out.

Caspo rejects the current status of the Wifi router as both a disregarded and unknowable black box. For Bardini, tactility and legibility were key:

“Current design typology impacts our behaviour. Why are we taking tactility away from these objects? Why aren’t they easier to use and understand? That’s what I want to question with Caspo.”

There is an inherent irony in Bardini’s design (acknowledged perhaps in its reference to the mischievous eponymous ghost) that introduces new digital technology to solve the issues that digital technology has delivered to household in the first place. “We create objects to make things easier for us but we often don’t understand what we’ve created,” he explains, “We then have to create more to fix those bad habits. That’s a natural progression of living with technology. The more ubiquitous it becomes the better we’re going to have to become at designing with it. That’s something I’m interested in… We have to be held accountable. We have to better understand ourselves and how we grow with technology.”

More:

-

Central Saint Martins Graduate Showcase

-

Leo Nataf and Tom Lellouche

-

Freya Holmes

-

Subash Thebe

-

Ana Rita Otsuka