In recent years, the concept of the archive has expanded. No longer relegated to the past, interpretations in artistic practice and theory have proliferated, taking on a multitude of new meanings for artists, designers and researchers. From categorising online dating sites to co-opting museological symbols, we take a look at the 2020 graduates who are reframing and reinventing the archive.

Traditionally, the archive was synonymous with the fixed. It referred solely to history – a place to keep the past distinct from the future. Now, the archive has come to be more fluid in its meaning. It is no longer simply a static, centralised bank of information controlled by those in power. Instead, the archive can now be understood to mean anything that has been retained: webpages, social media accounts, banks of data, personal histories, photographs and narratives. Today our lives are constantly documented. Instagram accounts are designed to accrue information in order to present a cohesive whole: a meal, day, a life, a project, an organisation. According to French historian Pierre Nora, “our whole society lives for archival production”.

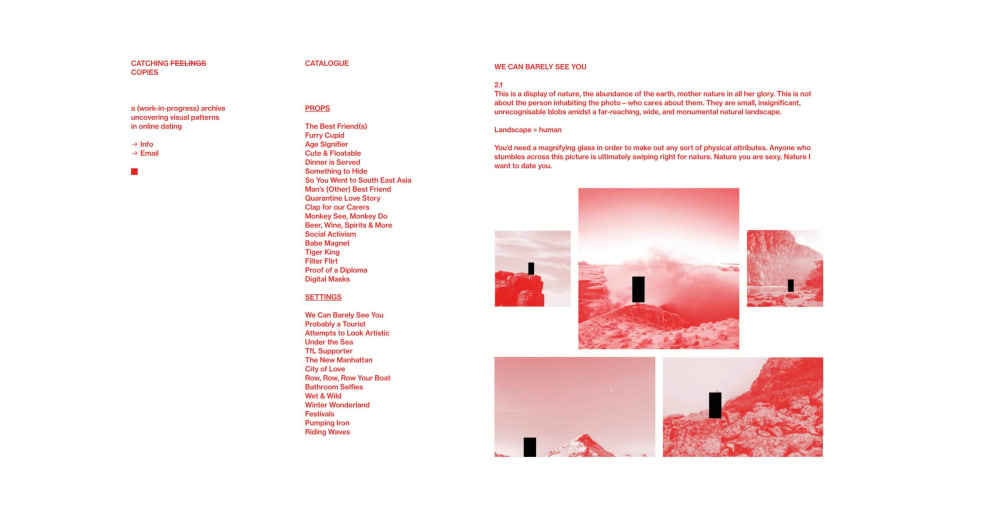

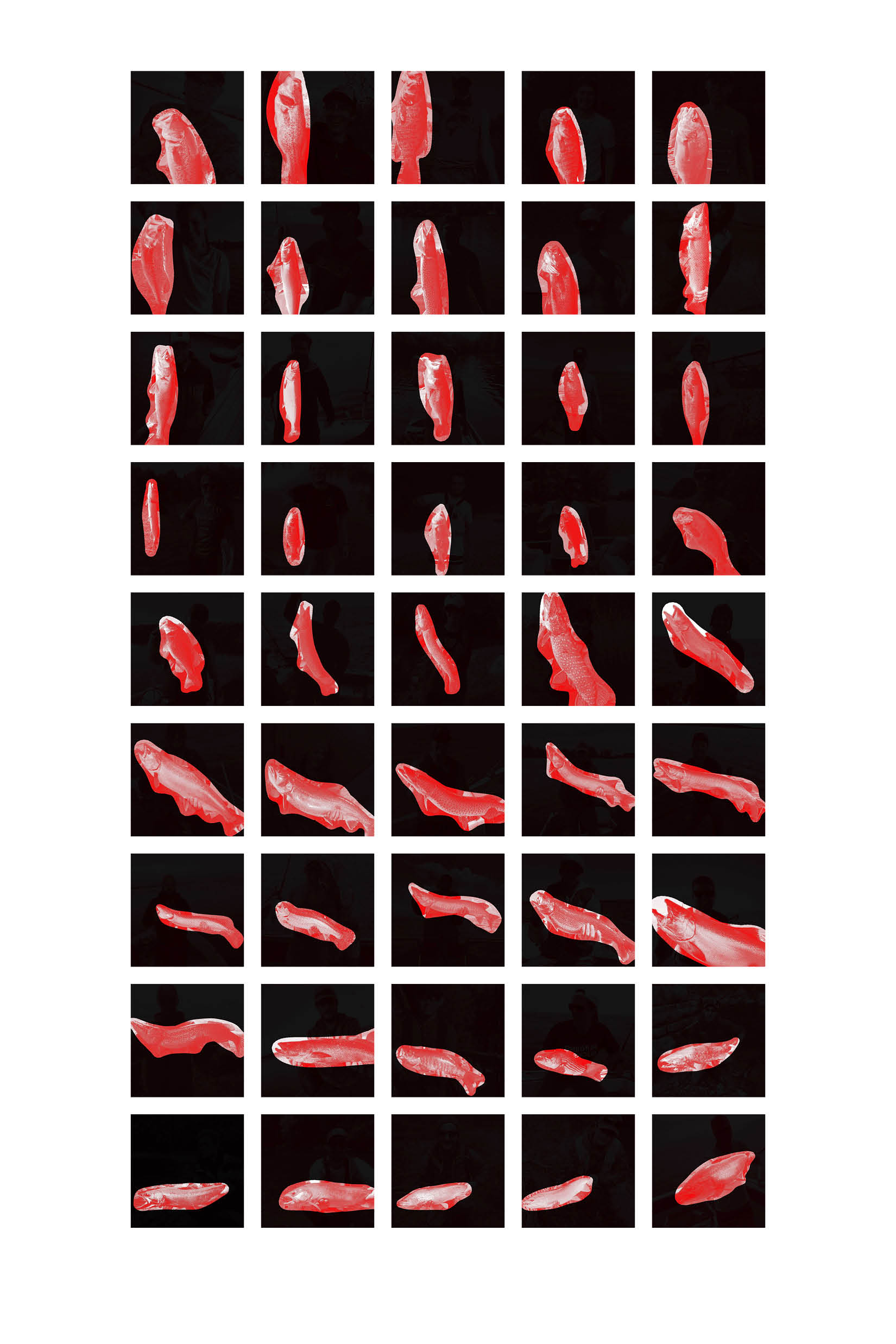

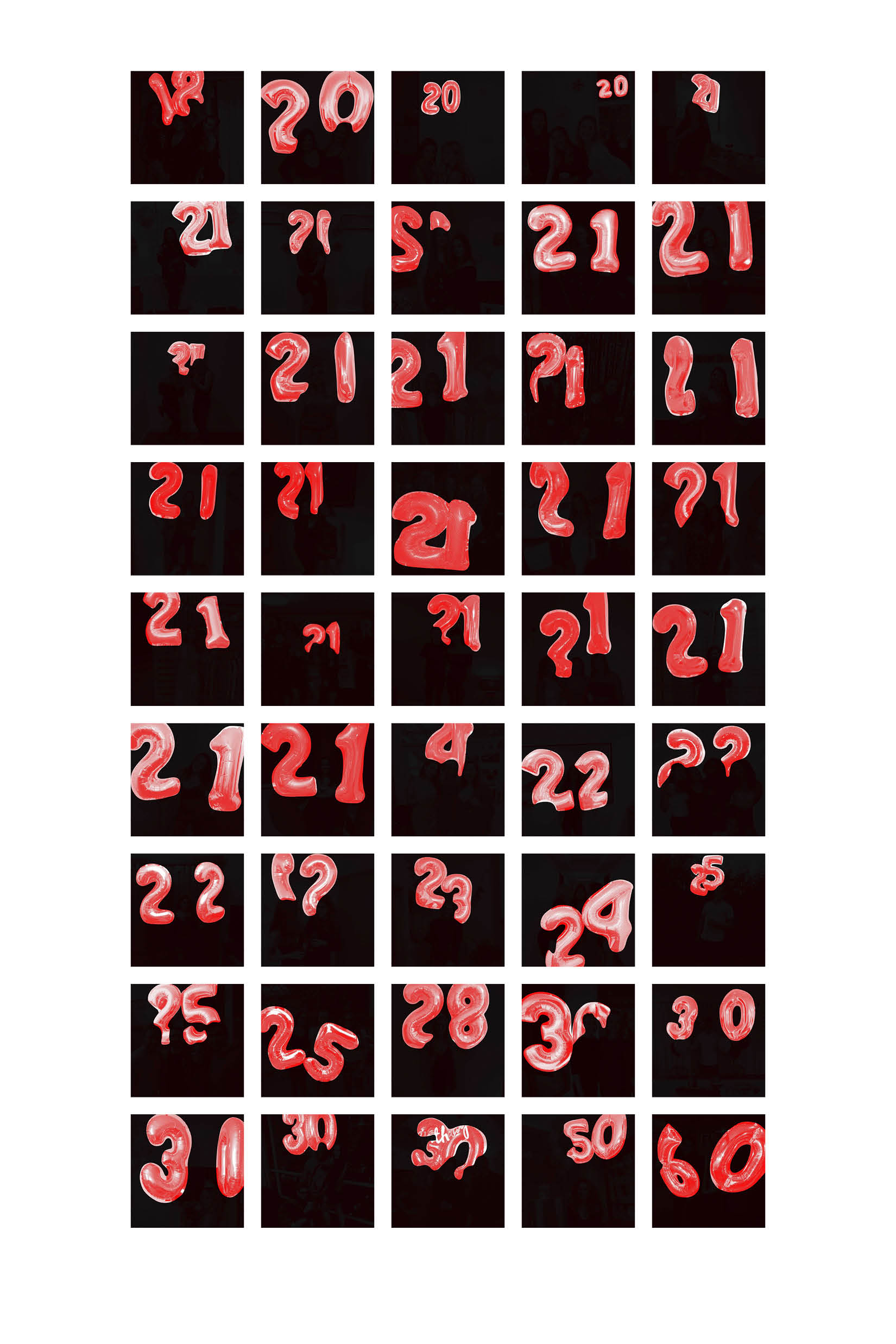

Sasha Grigorik’s project Catching Copies uses archival methods to provide systematic order to a chaotic image culture. In her final project for MA Graphic Communication Design, Grigorik turned to online dating sites. Through methods of categorisation and manipulation, she set out to uncover visual patterns across these platforms. Focusing on repetitive symbols and signifiers, she created a system of imagery which both emphasises and anonymises characteristics and trends: “I moved to London four years ago not knowing a single soul and online dating became a way to connect in a new city. I found the entire system to be quite addicting and humorous. I vividly remember picking out recurring patterns in photographs. I noticed that many other users were doing the same,” she explains.

Catching Copies, 2020

“In a way archives are puzzles; each individual piece carries a little bit of information and when you start to accumulate, organise and place each piece, a bigger picture is formed.”

Grigorik’s dating archive is split into two categories: props and settings. Mirroring theatrical conventions, props refer to any items or materials used by the person in the image, while settings are where the image is taken. Developing from this starting point, patterns reveal themselves – for example, The Best Friends, group shots which shout “sociability, likeability, lovability” (prop); and We Can Barely See You, photographs in which the subject is dwarfed by nature, “anyone who stumbles across this picture is ultimately swiping right for nature. Nature you are sexy. Nature I want to date you” (setting).

-

Sasha Grigorik, MA Graphic Communication Design

Catching Copies, 2020

-

Sasha Grigorik, MA Graphic Communication Design

Catching Copies, 2020

As the archive develops, categories start to form within categories. As Grigorik explains, “the choices are endless. The archive becomes a constantly shifting and evolving entity.” While Grigorik’s work reveals tropes within the online dating realm, it also hints at wider social politics and how we fall into archetypes while trying to represent certain characteristics. “This project has been going on over a year and it’s been eye-opening to see the archive actively respond to current topics around the world. Within two weeks of the COVID-19 outbreak in the UK, people in online dating were using face masks in their profile photos. Similarly, when the extinction rebellion protests were taking place, people began posting photos of themselves at rallies. This goes to show how people pick and choose certain photos for their profiles that suggest and visualise certain values.”

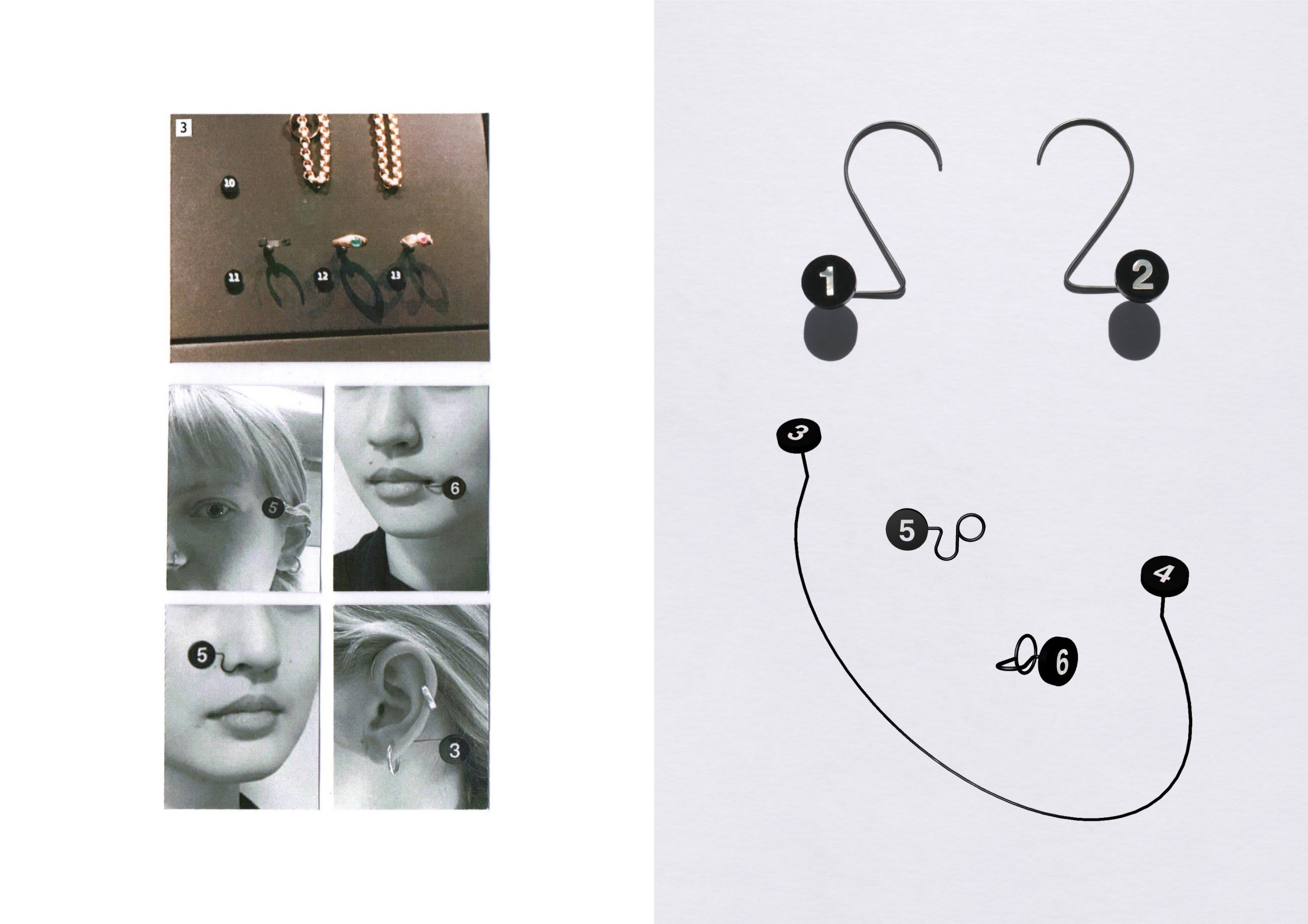

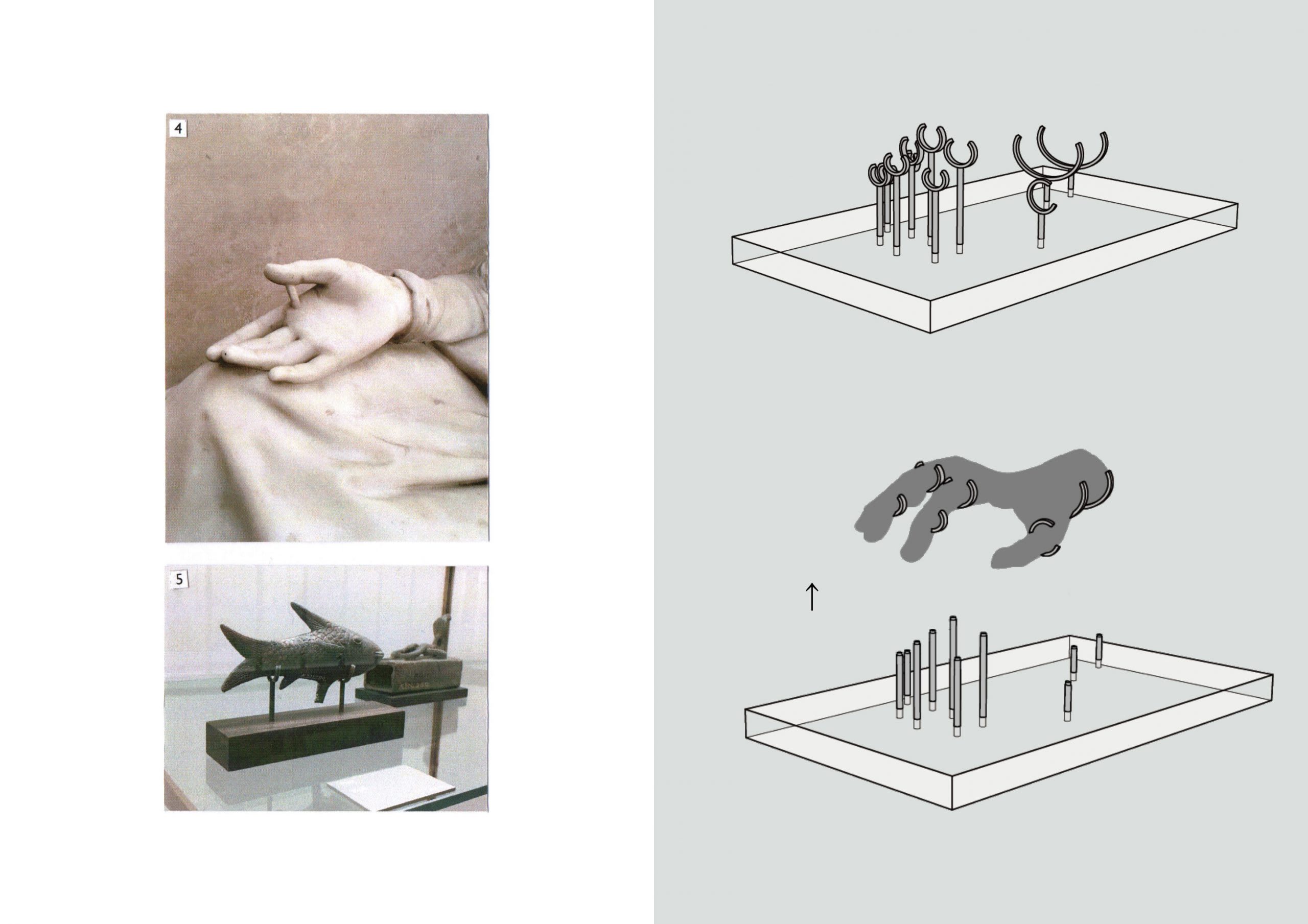

While Grigorik has taken a huge, expanding realm of information and begun the process of breaking it down into categories, BA Jewellery Design graduate Miho Ishizuka has taken pre-existing archival symbols and applied them to a personal entity: the body. In her collection The Body is Temporarily Removed, she has turned display conventions often seen in galleries and museums into jewellery pieces which re-frame parts of the body. The collection questions the fundamental role of jewellery and its relationship with the human form: “Principally the body can exist without jewellery, but jewellery needs some sort of relationship to body to be defined as jewellery. But when jewellery attracts attention and draws the gaze, our body tends to be concealed and blurred by the object,” she explains.

-

Miho Ishizuka, BA Jewellery Design

The Body is Temporarily Removed, 2020

-

Miho Ishizuka, BA Jewellery Design

The Body is Temporarily Removed, 2020

-

Miho Ishizuka, BA Jewellery Design

The Body is Temporarily Removed, 2020

“I believe that our body should be central and jewellery should be ancillary. I created this collection to celebrate the ever-changing body. It is based on display props – how they are ignored and meaningless by themselves but exist to tell us there is something else worth seeing.”

Ishizuka was initially inspired by a gold ring which her mother used to wear: “When she showed it to me, I recognised it from my childhood but at the same time I couldn’t remember anything about her hands: the shape, colour or texture. Instead, I had a vague image of a hand with the ring swinging in front of my eyes and me as a child trying to hold it. It was a little sad – thinking of her hand in the past, forever lost, yet the ring is here in the same shape and form.”

Ishizuka’s Numbering Pin series gives the visual effect of cropping facial parts, highlighting them by separating them from the rest of the face. Each piece is designed to hook onto the ears, eyes, nose or mouth. In an institutional context, numbering pins connect artefacts to captions, revealing information about the object to visitors. Here, their presence draws attention to certain features, indicating the importance of each “exhibit”. Ishizuka was also interested in the way this numbering system influences how visitors work their way around museums, often resulting in confusion and backtracking. “This is why I decided to allocate numbers 1 and 2 to the ears, where you cannot see them both at once.” Using ubiquitous framing devices, Ishizuka redirects our attention, displacing the attention on the object or sculptural form with the human form – presenting body as living sculpture.

Archive of Our Home

Em Bentzen Kraft

BA Ceramic Design graduate Em Bentzen Kraft’s project applies archiving processes to the everyday. Archive of our Home is an immersive experience which consists of raw clay vessels and performative projection mapping. Approaching her Nana’s house in Formby as an archival site, Bentzen Kraft explores topics of loss, family history, collective memory and time. She uses subjective experience and intangible sources such as memory and nostalgia – things we would often consider in opposition to the archival – to build an archive that mirrors daily human interaction.

“Archiving in my practice has become about documenting the human experience in an authentic and digestible way. Archives are often seen as elite forms of recording the events deemed ‘important’ enough to remember. I wanted to challenge this with my work and ask what are we losing by not documenting the everyday: the parts of our history that are forgotten when they aren't told. By taking ownership of archiving events and stories significant to them and their experience, we take the power to talk about genuine human experience.”

Archive of Our Home, 2020

Archive of Our Home, 2020

Bentzen Kraft’s project frames the family home – inhabited by generations, with people moving on and passing on – as an alternative archive. It challenges the dominant narrative of collecting and storing key information for historical purposes, to detail a wider society. Instead, her process builds up an idea of society through the individual, the lived experience in houses like her Nana’s. Originally created as a gallery experience, the work centres around a series of large vases which she created using the traditional coiling method. Film footage of family events is then projected onto the vessels, alongside a recorded narration from the artist’s grandmother – taken from phone calls between the two of them during lockdown, in which she recounts memories of the house.

For Bentzen Kraft, the archive takes on extra meaning during the process of reinterpretation – once they are activated in the present while documenting the past: “I am drawn to this idea in terms of my Nana’s house having all these family stories. The house has changed so much in many ways, the life of these memories can only continue if they are shared and talked about. Although this is a personal project, it is subjective and fluid – anyone can gain something from simply seeing it as a description of the human experience which we all share parts of.”

Contain/ing/ment, 2020

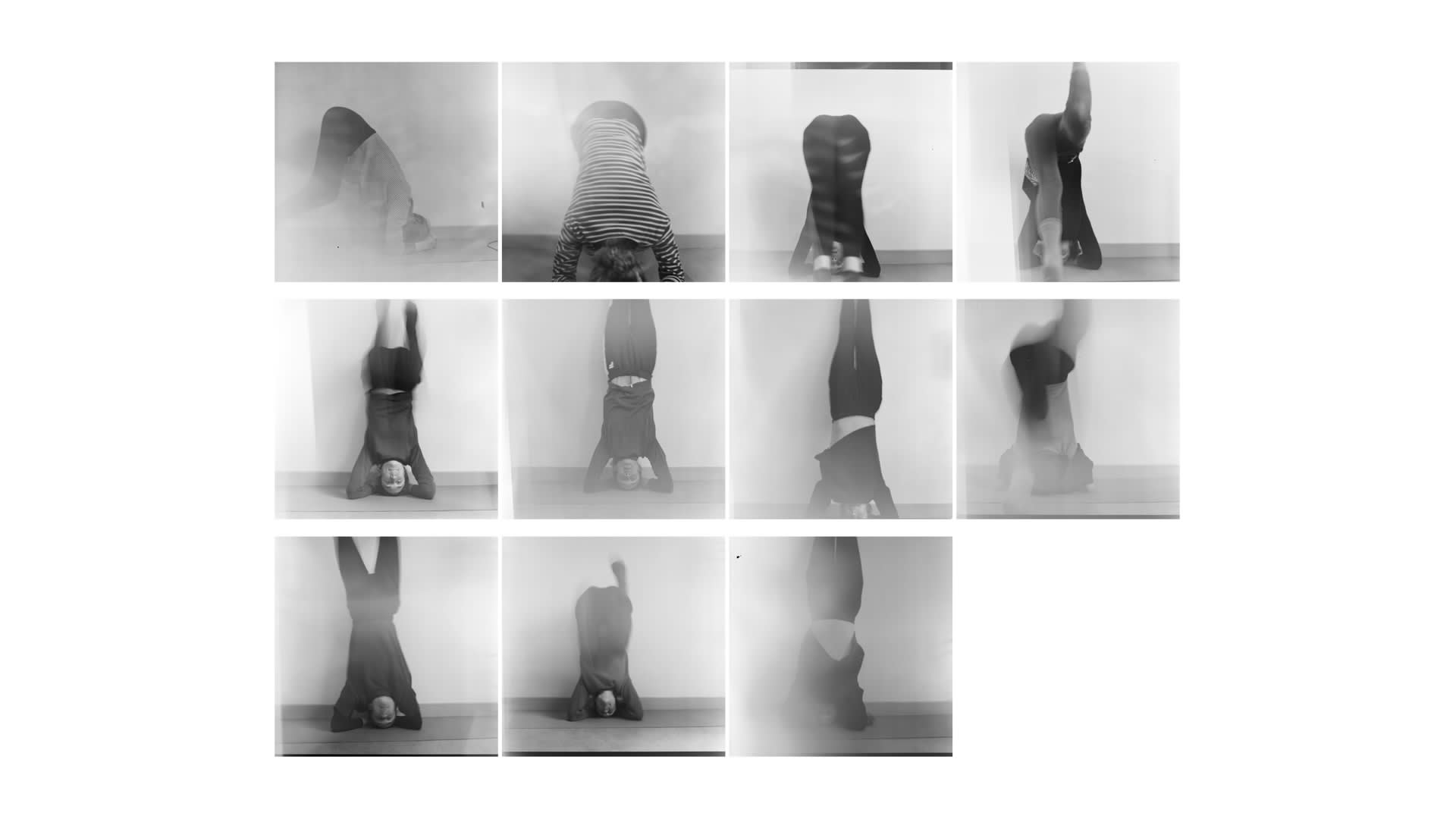

Turning to the archive as a holder rather than what it might hold, MA Graphic Communication Design graduate Francesca Forty’s project Contain/ing/ment questions how things are contained or what it might mean to contain. In her practice, she has investigated this idea literally (looking at items which hold other items such as baskets or bags) as well as topically (containing the coronavirus) and personally (the idea of containing oneself). Her final project is a website which attempts to hold the totality of her recent work, but also interrogates its own capacity as a container. The website ranges from interpretations of a “homepage” and a “home” to photographic documentation of the designer learning to do a headstand.

Forty’s website is an archive in and of itself, but it is also one which interrogates archival production and the idea of holding information: “I wanted to make a website where it felt like the contents had fallen to the bottom. This wasn’t intended to be a neat portfolio of my work, but a way of interrogating how to showcase work. What if it wasn’t one big main thing – but instead loads of bits rattling around together.”

-

Francesca Forty, MA Graphic Communication Design

Contain/ing/ment, 2020

-

Francesca Forty, MA Graphic Communication Design

Contain/ing/ment, 2020

“I’m interested in the idea of the archive that holds not only treasures, but also failed works and dead ends. I’m interested in the limitations of the archive – how wide spanning and tangentially linked are its contents? How much can it hold? Can it be overloaded? Does everything have to be labelled? Where I am wary of the archive is where it serves to box and label in a way that fixes things. Things aren’t always neat.”

Forty’s website brings together disparate photographs, videos, data and ephemera through its ability to contain. In recent months, it has come to exist as something of a dis-orderly archive of the lockdown period. Within her surroundings, she is often drawn to frames, screens, windows – containers or shapes which create their own boundaries: “These are also interesting to me where they fail to successfully compartmentalise. Or at the very least where their frame is exposed and shown for what it is. When working with the web in some ways the edges seem much less clearly delineated. There is no limit to the number of pages. There is no front or back as there might be in a physical publication. But the webpage does of course have its own limitations – how much can be seen on the screen at one time? Do you need to scroll?”

More:

-

Central Saint Martins Graduate Showcase

-

Anke Buchmann

-

Xuan Ma

-

Ana Rita Otsuka