In collaboration with the British Council, the Resilience in Residencies programme bought two Brazilian artists and their activism to Central Saint Martins.

In November 2018, Sheyla Maria Alves de Melo from Arte Maloqueira and Priscila Mastro from Fábricas de Cultura took up residence at Central Saint Martins. During their two-week stay, they encountered life both inside and outside the College – working with students from our Art programme and visiting local organisations as part of the CSM Public initiative. Across a range of activities, the residency examined the politics of exchange: how the institution engages with its partners and local communities; the social, cultural, economic and technology implications of contemporary art; and the benefits of collaborative action and participation. Bringing the agency of cultural activism from Brazil to the UK, the project challenged our own paradigms – of teaching and partnership – while also cementing institutional relationships between the two countries.

Brazil is renowned for connecting art and design practice with social and political engagement. Since a UKTI-funded trip in 2014, what began as a series of conversations and site visits between the College and various Brazilian institutions has given rise to connections across disciplines. Most recently, in 2017, a group of academic staff from our Art programme visited a number of São Paulo’s “favelas” or informal communities. Through talks, group meetings and workshops, they presented new technologies which could enable DIY offline networks – a resource which provides localised, secure communication among, and between, communities. While in the UK nearly 93% of the population are online, only 66% of Brazil’s population have access to the Internet. Furthermore, in the majority of the country’s favelas, Internet access is intermittent and unreliable. The tools explored with our team allow for autonomous, reliable communication, giving rise to action and participation.

A year after these visits, our institutional roots in Brazil extended into a new residency format in collaboration with the British Council. Cristina Becker, its Head of Arts Brazil, introduced the project as a “cultural exchange programme between members and collaborators of independent art spaces in Brazil and the UK.” She continued: “Resilience in Residencies aims to promote travel, immersion, courses, face-to-face meetings and virtual exchanges… Ultimately, we are sure that both Brazil and UK institutions will learn about the specific contexts of collaboration and will be inspired and challenged by sharing knowledge and approaches to community participation.”

In 2009, Melo co-founded Arte Maloqueira – a collective based east of São Paulo which utilises and promotes culture as a form of “resistance, liberation and human development”. São Paulo is home to several highly organised housing rights movements, many of which have turned occupied buildings into public housing units. In addition, more than 1.5 million people live in 1,700 “favelas” across the city. Most are precarious settlements and have been historically unregulated by the government. They have been developed by residents and often exist without basic infrastructure such as sewerage, water, electricity or rubbish collection.

“We like to call our community a quebrada and not a favela”, explains Melo, “We say the word quebrada with love. I always think of a phrase by poet Sérgio Vaz: ‘In the quebradas we are united by power, love and pain.’ The pain is because people do not choose to live in the quebradas, they are chosen. We use this exclusion as our motivation to bring something good out of something negative. So our action as a cultural group is to make people not want to leave the quebradas but instead to change the quebradas.”

The name Arte Maloqueira stems from the notion of a “simple or modest house”, she continues, “we try to promote the idea that people should live a simple life. This results in them becoming poets, writers and thinkers… In our district of Guaianases, although we have a population of 400,000 people, there is limited access to art and culture and we only have two libraries, so our cultural space needs to be able to move.” Melo’s collective is a transitory organisation, taking books, spoken word poetry, debates, broadcasts, performance and exhibitions directly into the communities themselves. The collective also make good use of DIY networking tools, adapting emerging technologies to create their own, autonomous modes of communication – such as radio shows – within and among the communities on the peripheries of São Paulo. Using an old Volkswagen, they established an independent, itinerant library and event space which can travel between communities and spearhead occupational movements. Their work relies on strategies for support and generosity, only in the past year have they received any public funding. After the year-long funding allocation, and with the additional impending budget cuts from Bolsonaro’s recently elected government, she says “I have absolutely no idea how things will go… How do you envision continuity without funding?”

Similarly, as part of her role at Fabricas de Cultura, Priscila Mastro also works in the peripheral neighbourhoods of São Paulo. Across eleven units in Brazil, Fabricas de Cultura, provides free, public access to a programme of cultural activities. Created with the objective of increasing knowledge through community interaction, they offer a wide range of events. Mastro works as Culture Supervisor of the Capão Redondo Culture Factory Unit, delivering a programme which champions social inclusion and personal development through art, music, dance, performance and debate. During their residency at Central Saint Martins, Melo and Mastro were taken to various local organisations near the King’s Cross campus by our Creative Producer for Local Engagement Georgia Jacob. “I think my role back home is similar to Georgia’s here”, says Mastro. “I work as a communicator between institutions, so I think we end up doing similar things – mediating between community and institution.”

“Priscila and I had really interesting conversations about the complexity of our roles and the challenges we face working in large institutions and with marginal urban communities,” says Jacob. “We discovered a shared belief that, although it’s not straight forward, it’s important for artists and disruptors to be working within these organisations. This is how we make things happen and help create change.

We discussed why we do what we do – irrespective of where we are in the world.” As a form of knowledge exchange, Jacobs hoped her time with Mastro and Melo would inspire and inform the College’s approach to community participation. “At first, it could seem as though we are worlds apart,” explains Jacob. “What has Central Saint Martins, an art and design school based in a muti-million-pound, state-of-the-art building in the centre of London, have to show in terms of any local socially engaged work. But, luckily, we do have much to share, and much to discuss. Sheyla and Priscila asked some pretty direct questions around the ethics of our local engagement work and the benefits for local residents. These are very important questions and ones that I constantly ask myself of the work I help produce.”

Their first group visit was to Maiden Lane – our neighbouring housing estate in King’s Cross. At its heart is the Maiden Lane Community Centre, which offers services and facilities to a huge number of local residents. Here, Melo and Mastro met staff from the Centre’s pre-school, which serves local children between two and four years old. The Centre also works with teenagers, providing them with a range of activities and equipment, including musical instruments and a recording studio. “Although we are working in different contexts, the projects at Maiden Lane are very similar to work we are carrying out at Fábricas de Cultura,” says Mastro. “We also offer free activities for children, youths and adults living in ‘vulnerable’ areas of São Paulo. Seeing the work carried out here in the UK made me realise just how important it is to continue with the projects we are doing in Brazil.” These parallels encouraged Mastro to think about establishing a more official dialogue: “I spoke to the staff at the Centre and we are keen to work with them remotely when I’m back in Brazil, engaging the young, local communities of London and São Paulo.”

Housed on the first floor of the Centre is the Camden Town Shed – a community shed created by its users. Set up mainly for woodworking, the Shed provides space for people to work on projects at their own pace. “As an activist and a feminist,” explains Mastro, “I am always involved in projects with women. So, for me this was very interesting – to see men, who were mostly unemployed or looking for work, spending time together. One of the organisers explained to me that the Shed aims to give men something useful to do, where there is the possibility of falling into drug or alcohol addiction. It’s still rare for men to talk about issues, so providing them with opportunities like this to work together is very important… Back in Brazil, I would also like to introduce a similar activity in order to bring men together. We need something to tackle issues of unemployment in our country, at the moment there is very little being done to address this.”

Discussing her own experiences with Melo and Mastro, Jacob concluded: “I was hugely inspired and challenged by these two incredible women, artists and political activists. I learned about the complex political landscape in which they have to operate, the daily struggles they face – the constant threat to their arts funding, and also even sometimes to their lives. But at no point did they ever show any reasons to quit. On the contrary, these challenges fuel them to continue fighting for their creative programmes in Brazil. They do it for their communities and their commitment to this work is exemplary. The few days I spent in their company made me consider the importance of the work I do here at Central Saint Martins. Crucially, this encounter really helped validate the projects we run both in São Paulo and London and gave, I think, all of us some much-appreciated time and space to reflect and celebrate the important role of the arts and culture in society.”

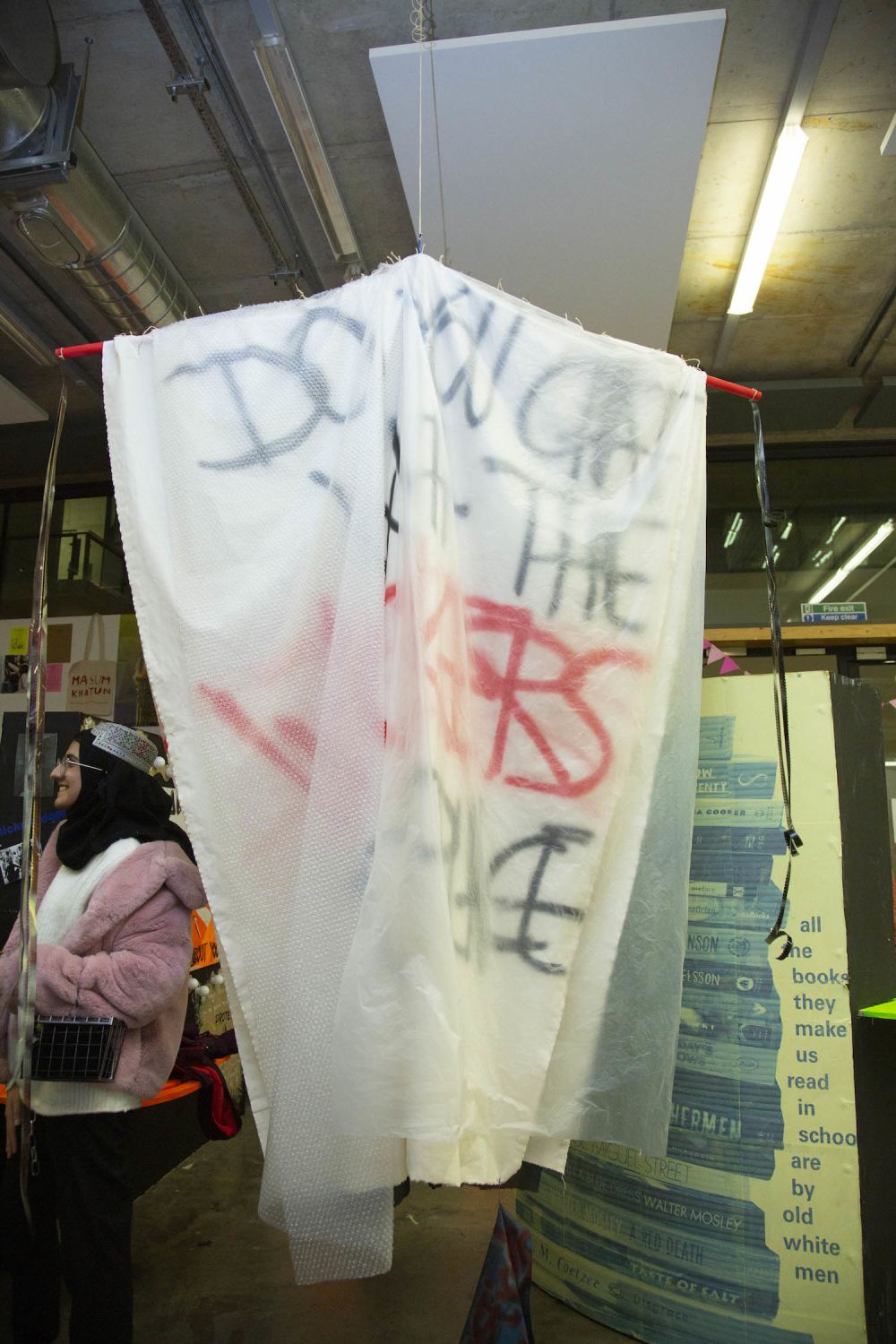

The site visits with Jacobs were also organised to give Melo and Mastro a diverse experience during their time in London. Reflecting on her time in the city, Melo mused, “Before I came to London, I saw it as a perfect place, I didn't think there would be issues such as this.” These reflections extended into her experiences with our Fine Art students, who were working on a project with lecturers Elizabeth Wright and Anthony Davies about labour and outsourcing contracts in institutional contexts: “In Brazil this is already a reality, so it was interesting for me to come here and actually have to face that it’s not just our problem.” During the residency, our students were working towards their Open Studio event – which was open to public audiences for the first time. Across a range of interventions, the work addressed themes of industry, provocation, care and visibility. As part of the exhibition, Melo also presented an artwork in reaction to these issues, in which she painted the phrase “CARE ABOUT PEOPLE SO THEY CAN CARE ABOUT YOU” on a piece of mirrored glass:

“To me, art is the tool to make change. It’s important that students are engaging with these sorts of issues. Any form of revolution takes time, but it’s important it’s there. Mine and Priscilla’s works in the exhibition were both an attempt to humanise our relationships. We tried to bring people together – it was very important for workers, students, staff and us to share the same space. So, our main idea was to build that bridge between different people. Any artistic intervention must not be selective, it can’t be aimed at just one type of person. You can’t exclude anyone.”

Fine Art Open Studios

Mastro’s contribution to the exhibition was one of her Figuras – an ongoing site-specific project. Translating literally as “figures”, these works are fabric constructions made out of recycled material and placed in locations around São Paulo and beyond. The work is ephemeral in nature, left to deteriorate or to be removed. She sees them as “figures to fill the void of herself and city, activating life and space”.

“These works do not belong to me,” she says, “they belong to the world, they are not mine, they do not belong to an individual. They should be out there, part of the world.”

Before coming to London for this residency, Mastro notes that she saw her work as an artist, her experiences as a psychologist and her role at Fábrica de Cultura as very separate strands: “Although over the past few years I have done some workshops at the institution which use similar processes as my Figuras, these things have been completely separate. It was interesting because when I first came here, I found it difficult to answer questions about my role: what do you want to know – me as an institutional person or me as an artist? But, now I see more crossover – when I want to make a ‘figure’ to fill a void or make something visible, then I think of our work at Fábrica de Cultura. We also have to bring to the surface things that are hidden, we have to make visible those who aren’t visible. So I think making my own work does strengthen the work we are doing in the institution.”

The residency culminated in a debate at Central Saint Martins around the topic of art and activism. Moderated by Alex Schady, Programme Director of Art, Mastro and Melo were in discussion with Fine Art Critical Studies Lecturer and writer Paul O’Kane. The debate addressed interpretations of community, vulnerability and provocation; the impact of music in activism; and the role technology can play in revolution. Opening the debate, when asked how community is defined, Melo replied:

“I believe common interests, common desires and common suffering makes a community. I don’t glorify pain, but it does often unite us. When we have a common enemy then communities can become stronger more quickly. In Arte Maloqueira, we try to think of capitalism as our common enemy. Capitalism tends to reduce human relations, to turn them into consumerist choices, avoiding the more complex reality. This may be utopian but it is this utopia which drives us.”

In relation to the connections between activism and technology, she continued: “I think that technology has a central role in de-naturalising things. In Brazil, it (specifically WhatsApp) led to the dissemination of fake news which is what elected the president we have now. It’s interesting for us to think about – how technology can be a tool to reach more people and to create a revolutionary process. But we also must be critical of it. Our strategy was to produce things ourselves – newspapers, radio shows. We produce these things with people so they can see that what they make is better than what they consume.” In addition to its physical mobility, Arte Maloqueira uses autonomous, offline networking tools in order to circulate their own broadcasts. Despite the clear advantages of technology in terms of disseminating information, both Melo and Mastro remain critical of its impact: “It brings an empowerment of information,” says Mastro, “but as Sheyla says, it also brings a denaturalisation of things that are meant to be, and the naturalisation of other things like police violence.”

Art and Activism Debate

A large portion of the audience was made up of London’s Brazilian residents and naturally, the debate turned to the implications of Bolsonaro’s 2018 election win. Speaking about the widespread, impending uncertainty, Melo said: “We need to unify our struggles. The groups I used to have little differences with in São Paulo, I now go and speak to, and say let’s forget our differences and work together because otherwise we are not going to be able to survive.

Groups like ours, we are going to need absolutely everyone. We are autonomous, we are independent. Our strategy has to be let’s unite and bring people to our struggle... We will use creativity to make this revolution.”

Reflecting on their experiences in London during the residency, Melo and Mastro were both focused on relationships and the need for support. Speaking in relation to our teaching processes here at Central Saint Martins, Melo commented: “We are always focused on the end result back home – maybe our process is something that we have to change. We tend to think ‘oh we need to finish that’ but here, I have seen people give much more value to the process itself. This is something we can take back to Brazil; we could focus more on the relationships with the people we are working with, instead of just focusing on the end result.” Similarly, Mastro reported a renewed interest in connection, with the hope of developing a 2019 residency project across partnering institutions, so “young people from the peripheral regions can experience the spaces in Fábricas de Cultura, but also those throughout São Paulo, Brazil and the rest of the world.”