Inga Kaugsay / Habitar Inga / Inga Dwelling is a multicultural, multilingual collaboration between Inga indigenous architects, Colombian architects, and the Spatial Practices programme at Central Saint Martins. A carefully co-authored knowledge mapping publication makes rich layers of Inga habitation practices accessible to many, resituating the knowledge with new generations in the Inga homelands.

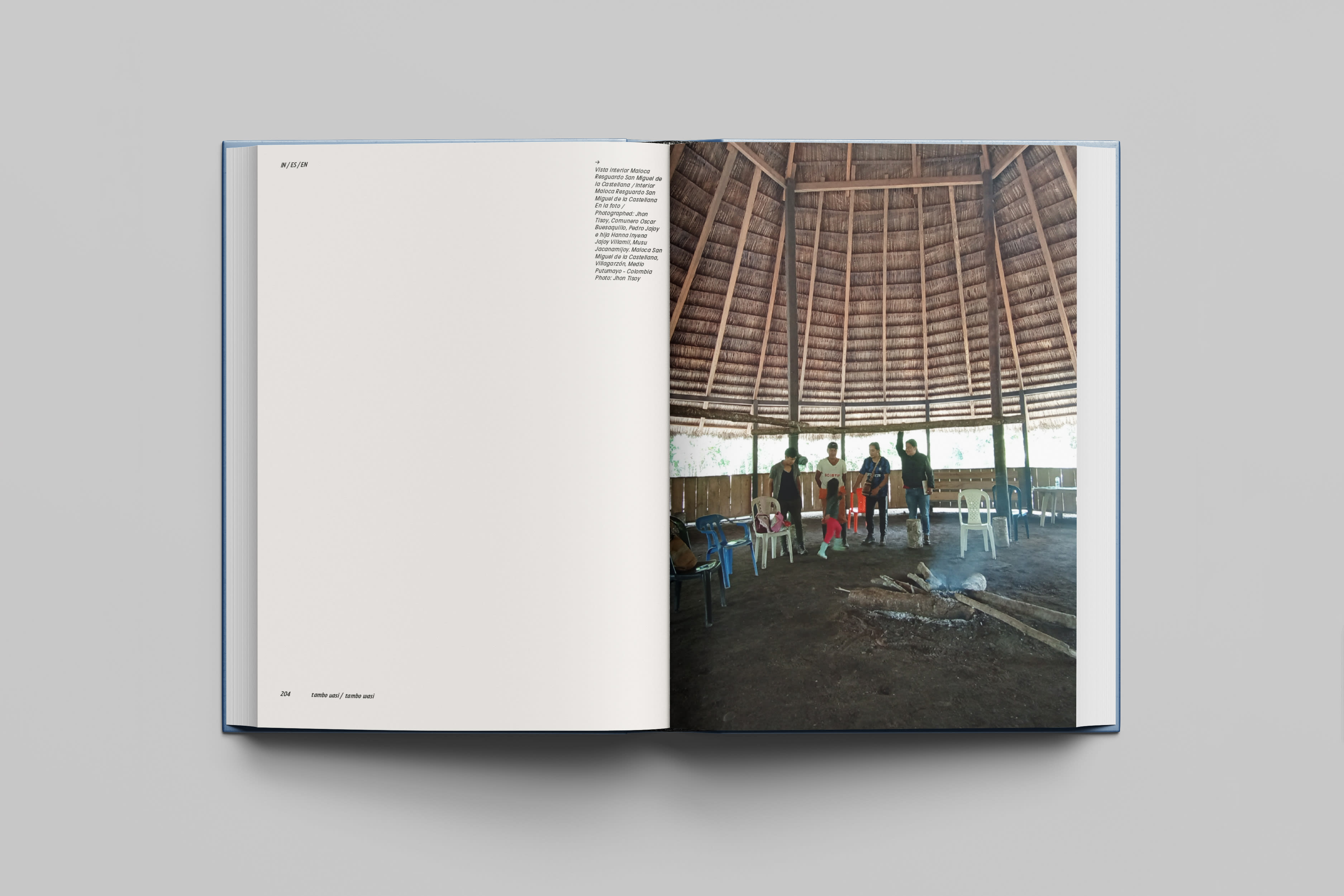

The Inga Kaugsay / Habitar Inga / Inga Dwelling project team - architects Musu Jacanamijoy, Pedro Jajoy, Jhon Tisoy and Colombian architects and spatial practitioners Catalina Mejía Moreno and Juliana Ramírez - have spent over two years in collaborative research, community dialogue and on information gathering walks, capturing specific types of knowledge in seven ancestral Inga indigenous territories in the Colombian Andean Amazon. Their experiences are documented in a 500-page publication that maps Inga ancestral living knowledges: language, practices and forms of living that weave together the symbolic and ceremonial as they manifest in the Tambo Wasi and its material, technical and constructive definition, and acknowledging the Inga relationship with the territory and new ways of dwelling.

In Inga and Spanish with an English insert, it is a starting point for today’s communities in the territories and wider humanity to honour the Inga People’s approach to their living knowledges and engage with their threatened language.

At CSM, we celebrated the process this ongoing project has entailed with the exhibition Inga Kaugsay,13 March to 10 May 2024 in CSM’s Window Galleries. The exhibition was co-designed and co-curated by Graphic Communication Design Senior Lecturer and publication designer Abbie Vickress and Spatial Practices Senior Lecturer in Climate Studies and publication co-author Catalina Mejía Moreno.

In this interview, Abbie, Catalina and student Holly Le Var reflect on their experiences of the project, working with indigenous knowledge and cultures of care embedded in the environment.

-

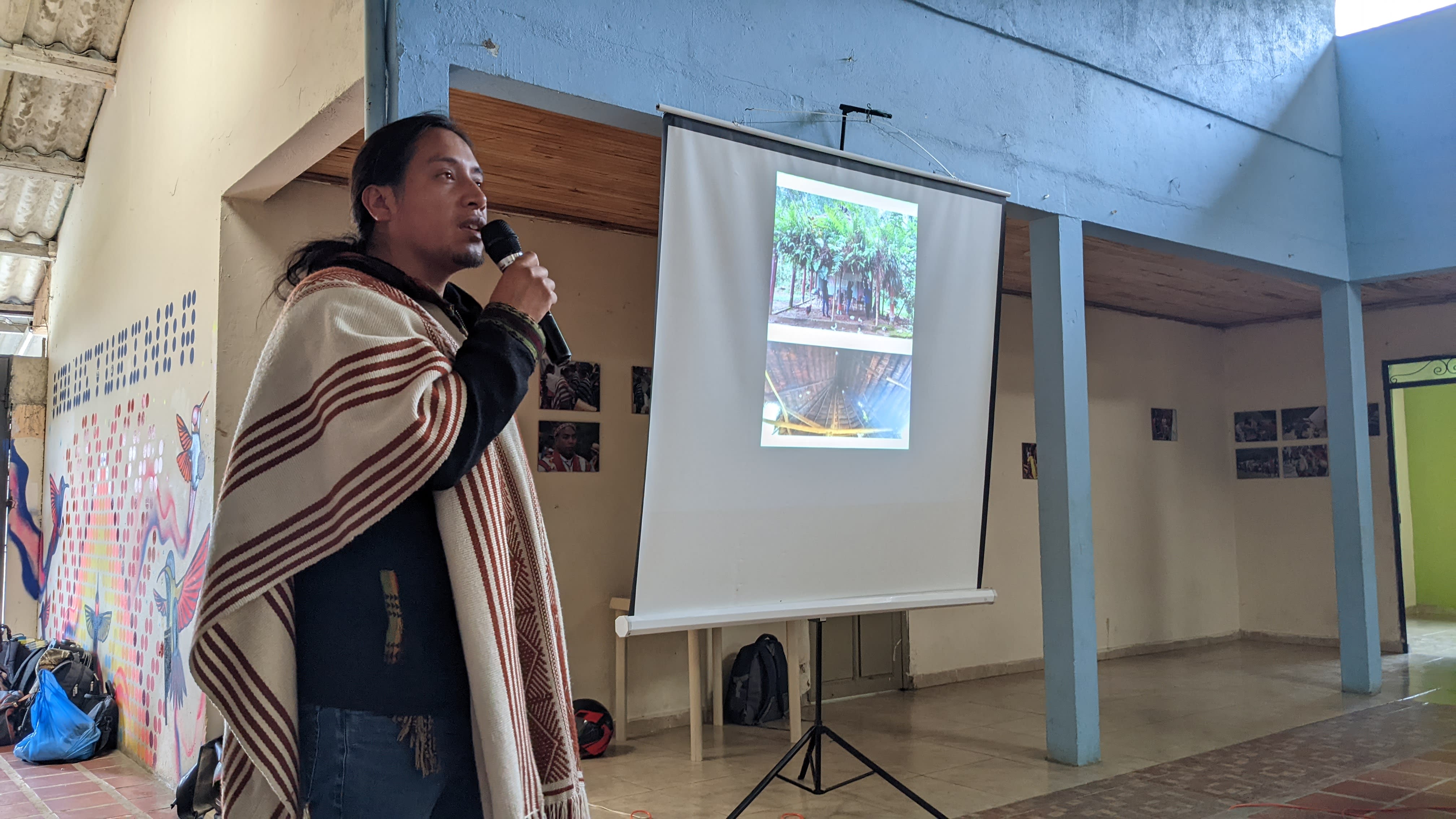

Pedro Jajoy presenting Inga Kaugsay's process to Inga authorities in Valle del Sibundoy. Photo: Wilton Jajoy, Ñambi Rimai Collective.

-

Editorial workshop with authorial and editorial team, Bogotá, February 2024

-

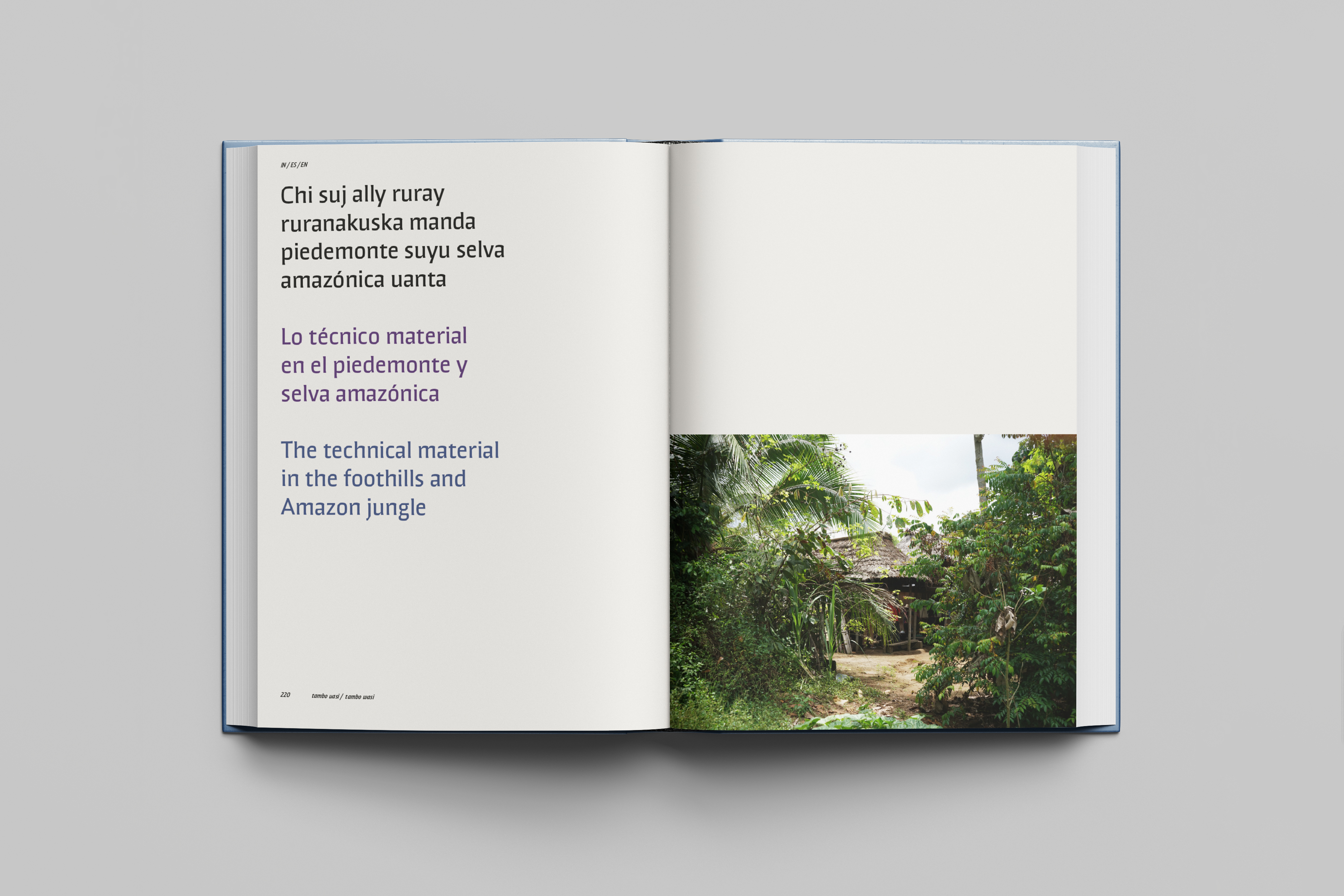

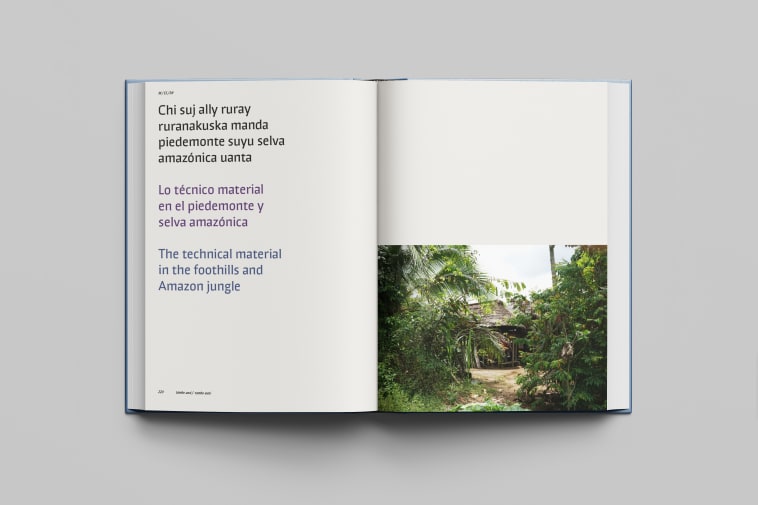

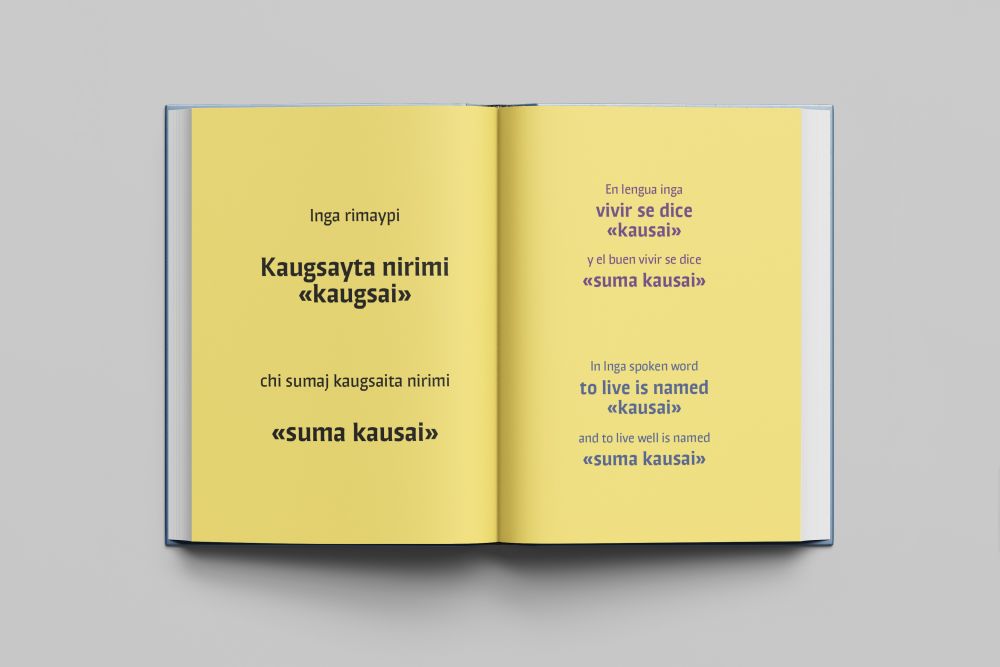

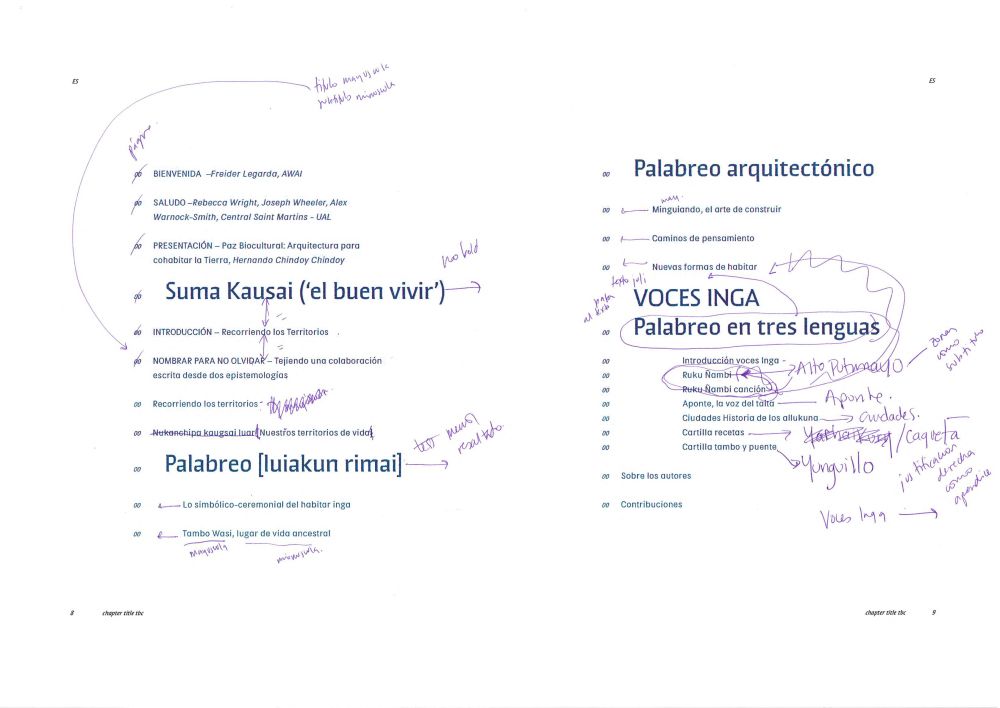

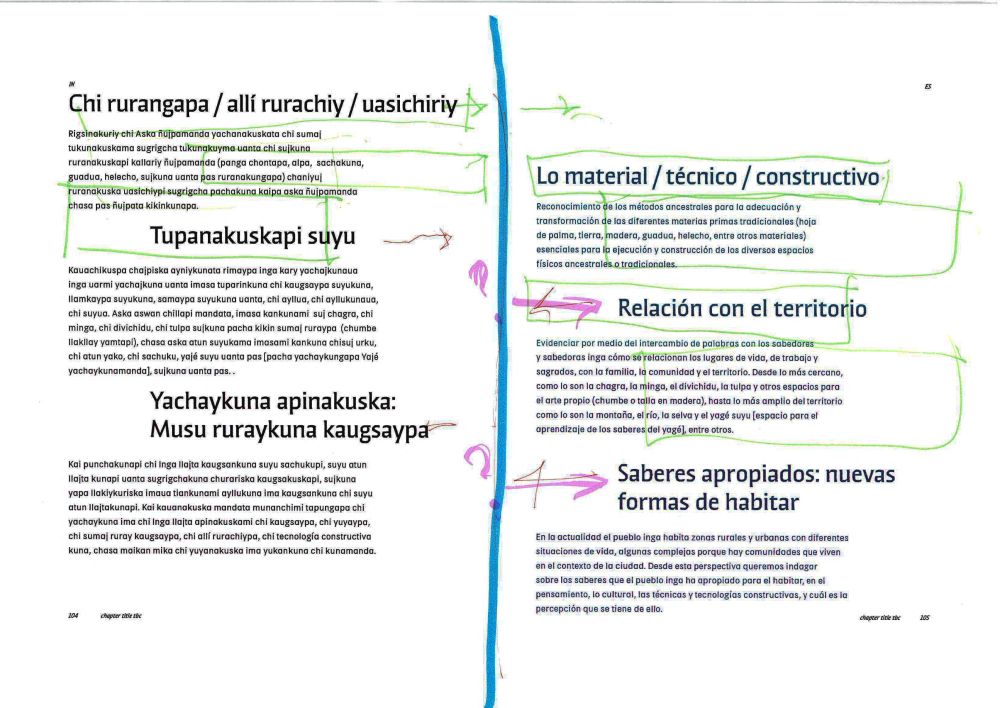

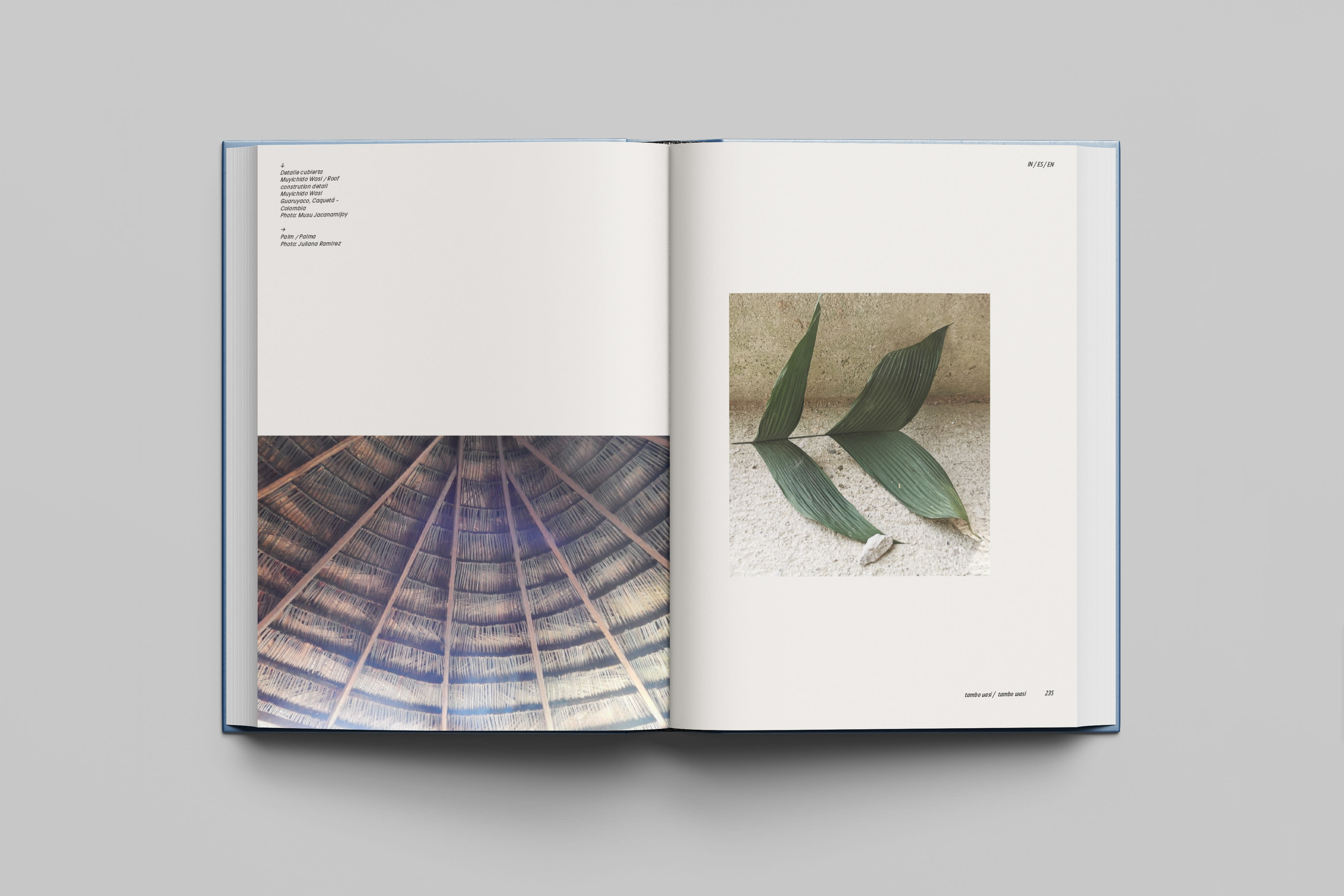

Spreads from the Inga Kaugsay publication. Graphic design: Abbie Vickress.

More than 500 years on, how are the ancestral habitation practices of the Inga relevant to communities today?

This is an important question for both the Inga Peoples of Colombia and for all worlds around them.

The reason why we embarked in this project was for the Inga to revisit, acknowledge and honour their ancestry, in light of their ongoing project: the consolidation of the Inga AWAI university. The mapping of the Inga ancestral territories in the Andean Amazon – where it all started, as a mapping of the Inga’s dwelling knowledges and practices – is a search for their cosmologies and cosmogonies and a recognition of a way of living that emerges from and is inextricably tied to their lands and territories. It includes a re-recognition of their eight ancestral territories, and of spaces such as the Tambo Wasi (term coined by the Inga originating from the word 'tambo,' referring to the gathering space in the family home), that even if present for centuries, has been changing and adapting to the changes faced by each territory. It also is a recognition of Inga as a living ancestral language. This publication, only the second written in Inga, aims to honour Inga ways of living, which are threatened and at risk of being forgotten through language instability, therefore, translation–or lack thereof–was a key part of the publication conception and design. We are mentioning this because Inga Kaugsay / Habitar Inga / Inga Dwelling aims to re-recognise and honour Inga ways of living, which together with their ancestral language are also today threatened and in risk of being forgotten.

Inga Kaugsay / Habitar Inga / Inga Dwelling is an exploration that is as relevant to them, as Inga Peoples, as to us. It is a call to safeguard - preserve living memories and practices - and a call within their community for those who hold ancestral knowledges to openheartedly share them, so that they can be passed on in written and multilingual form with new generations that wonder about Inga dwelling. We hope this exercise also informs pedagogical spaces within the Inga territories, as well as other spaces of sharing: assemblies, mingas (collective work or thinking) and many of the other moments where the Inga peoples weave together words and beliefs.

It is important to mention that this mapping is in no way complete and has its limits. Not all territories were possible to visit, not all voices where possible to include. We see its importance in it being the first multilingual publication that includes Inga language that embraces questions related to Inga dwelling, and in it being an invitation to the Inga peoples to continue weaving together. And to other communities and worlds around it, to honour and recognise the invaluable significance that these living knowledges hold.

As a pluricultural team we wanted to open a door by offering this initial mapping to other worlds, whether in Colombia or beyond. We recognise this book as an invitation to continue expanding and asking ourselves about ancestral ways of living and the cosmologies and cosmogonies tied to them. But we also see the need of strengthening these dialogues as they also can resonate with our own forms of dwelling – from everyday practices to ritualistic, the spaces we occupy, and the ones that will come in the future.

What were the values guiding the mapping project?

Deep listening amongst all, humbleness and respect. Listening to the elders, mamitas and taitas that were wholeheartedly willing to open and share their living knowledges with us, as they also manifest in their living and sacred spaces; to all families, leaders, elders and children who welcomed us in their homes and community spaces, who joined us across territories in mapping exercises and sharing sessions.

We also listened to ourselves as we immersed in these journeys, and discussed what we believed we could do in response. Listening to our collaborators, to everyone who was involved in this publication in one way or another – from our editor Yanina to the translators Benjamin, Paula and Emilio, and Abbie as graphic designer; to all the different communities who contributed with a recipe or a story; the Inga community in their cabildo (indigenous governmental house) in Bogotá when we came to share the first draft in February this year. Listening and co-creating together made this publication something distinctive: that it embodies the Inga tradition of weaving of knowledges, voices, words, paths, practices and experiences.

Describe the kinds of knowledges and relationships between things that the mapping project reveals?

[Catalina:] I will speak here from an architectural perspective. We – and here I mean all the authorial team - went through important realisations throughout the process. All formed as architects, and hoping to inform the design of the constructions that will host the Inga University, started with an idea of mapping as a search for Inga architectures in their physical and material manifestation. The journeys across territories asked us to rethink, broaden, and amplify this query. Architecture in its porous nature manifested itself as a question of what dwelling means and symbolises for the Inga peoples of Colombia in their ancestral lands. This implied observing and embracing different forms of life – as is the ritual of lighting the tulpa (the heart and place of fire) and share while sitting around it. To enter a symbolic space respectfully if it is the place where ancestral medicine is taken and to the chagra of a mamita. Or re-learning that sacred plants should be used when asking permission from the spiritual beings who guard the territory and to harmonise it before it can be inhabited and constructed upon.

-

Spreads from the Inga Kaugsay publication. Graphic design: Abbie Vickress

-

Spreads from the Inga Kaugsay publication. Graphic design: Abbie Vickress

-

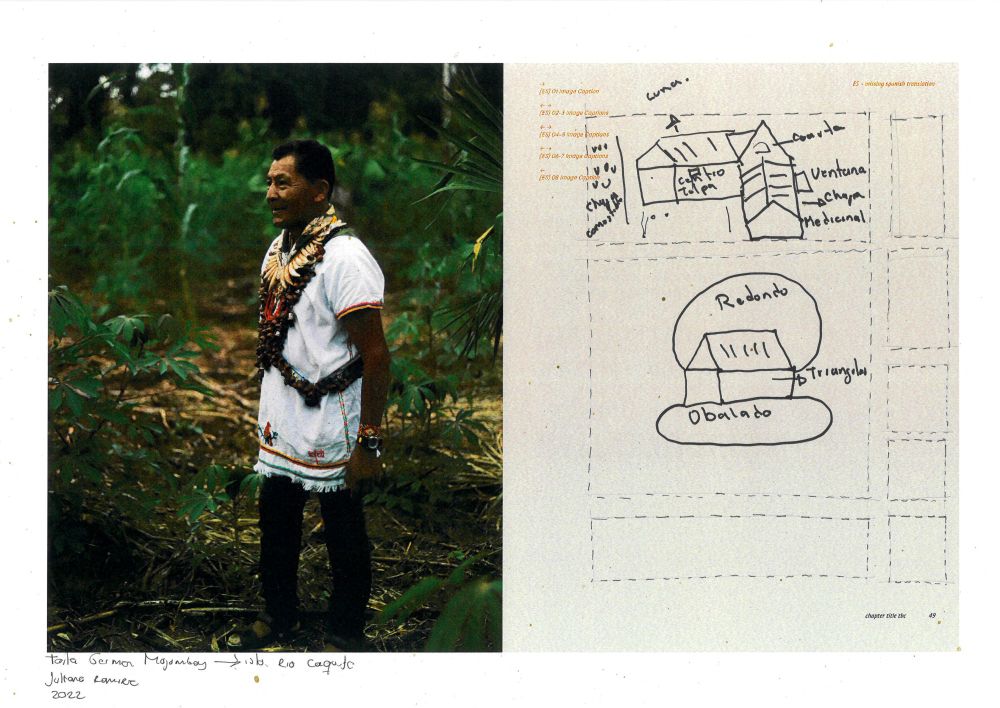

Taita German Mojomboy and his family with part of the publication's authorial team, Rio Caquetá Colombia. Photo: Janosch Kirchner

How was the publication designed?

The design of the publication posed many ethical questions around extractive knowledge practices – who gets to produce or document this knowledge, and who this knowledge is for. Therefore, from the offset it was evident that the design process was to be a collaborative dialogue, through conversations, workshops and ways in which the Inga and collaborators could meaningfully contribute to design choices.

From decisions to include design elements born from dialogues and workshops, the placement of an English insert as not to disrupt the translation/relationship between the Inga and Spanish languages, design choices that reduce the carbon footprint of production, and financially investing in Colombian typographers as a visual grammar with a relationship to the area.

How important to students is the opportunity to engage with issues around climate and colonisation?

It is urgent that students commit to producing work that addresses and engages with the complexities that colonisation practices and different forms of violence have caused, and keep causing, to the planet. Bringing the publication and the experience behind it to the classroom is also an invitation to us, and to the student body to think together on the relevance of this project and its broader questions.That they recognise colonisation as the principal cause of climate change. That they understand – and embody – the ethics of collaboration with other worlds and indigenous communities - which historically have been defined as extractive, and which urgently needs to stop and to change. That they furthermore recognise their agency within this, and the change they can foster.

From a spatial practices and graphic communication design perspective, we hope the publication and exhibition serve as an example of the ethical complexities and rewarding nature of designing alongside such a generous community. In time we hope to use this publication as a teaching and learning case study to counter the historic complicity of design in extractive, colonial practices.

What does this project bring to our teaching practices at CSM?

One of the beautiful experiences that this project has allowed us was to host some of the authors of the publication in Spatial Practices and within our teaching spaces. Musu and Juliana joined us in the first year of BA Architecture last year and shared with us some of the observations and experiences of the first mapping, Pedro later joined us in the M-Arch collaborative. It marked many of our students. These experiences are something that students still return to; we see it in their projects and attitudes towards their practices.

Bringing the publication and the experience behind it to the classroom is also an invitation of us, and the student body to think together on the relevance of this project and its broader questions. This publication has also been an invitation for us to think about translation – translation of languages, of forms of living, even of words. How can we translate this experience into our classrooms, with the same significance that this project has brought to us and all involved.

-

Inga Kaugsay exhibition, Lethaby Window Gallery, CSM. Photo: Jamie Johnson @endorstooi

-

Inga Kaugsay exhibition, Lethaby Window Gallery, CSM. Photo: Jamie Johnson

-

Inga Kaugsay exhibition activation – Indigenous Tools (monoprint) – by Holly Le-var, March 2024. Photo: Jamie Johnson @endorstooi

Holly Le Var, student

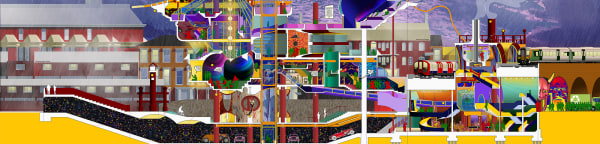

What was the work you created in dialogue with the exhibition material?

As part of the exhibition, I produced a wobbly taxonomy of abstract instruments, embodied construction techniques, natural artefacts, and ancestral symbols drawing from my learnings and research into Inga culture. My taxonomy took the form of a large format wipe-away monotype which was printed onto a long piece of fabric. This process involves rolling the ink out onto the table and wiping the ink away to create shapes, line and forms. As a mode of analysis, I often use monotype printmaking to foster more considered understandings of the people, meanings, and feelings I encounter.

Abstracting my findings into ambiguous shapes is perhaps an attempt to remove myself from the biased first impression and develop textural archives which have the potential to become actively and consciously translated or de-coded. Throughout this process, it was important to convey the extent to which the Inga is an abundant, sacred community which exists far beyond this singular interpretation. This print can be observed as my personal attempt at (beginning to) comprehend the sensitive, woven and complex relationships they (and we all) have with their territories.

How does this project enrich your design practice?

Much of my work stems from a background in Spatial Practice, in which I utilise space as a vehicle and resource for engagement, performance and play. Encouraging participants to care, respond to and build empathy with their collective landscapes are essential pillars in my practice. This project has added another layer to this methodology. I begin to question; what does truly connecting with our territory really mean? What stories can we tell in order to protect it? If I were to tell the story of our land, what would it say? In my culture, we have so many entrenched and rigid ways of thinking which often separate us from our ecology. Through my response to the Inga Dwelling project (and due to their gentle willingness to share), I am reminded to meditate or step back, place my hands on the ground, pause and breathe before I speak.

The publication is in final production and its initial online iteration will be published online through CSM’s Afterall research centre. The CSM team would like to bring print copies to the Inga community in Colombia alongside the travelling exhibition designed for the Lethaby Gallery Windows. If you would like to support the project and for updates, please contact Catalina or Abbie.

Project credits

Inga Kaugsay / Habitar Inga / Inga Dwelling co-authors and project team:

Musu Jacanamijoy @musujacanamijoy

Pedro Jajoy @pedro.jajoy.j

Catalina Mejia Moreno @catalina_mejia_moreno

Juliana Ramirez @checa_

Jhon Tisoy @jhontisoy

In dialogue with a wide range of voices and collaborators

Publication design: Abbie Vickress

Editor: Yanina Valdivieso

Translation to Inga: Benjamín Jacanamijoy Tisoy

Translation to English: Paula Winograd Caycedo and Emilio Yügue

Inga voices

Freider Jaime Legarda Mojombo

Hernando Chindoy Chindoy

Antonia Agreda

Wilton Gilberto Jajoy

Ñambi Rimai Collective

Serafín Jajoy Mujanajinsoy

Educational Institution Yachaikury

Yeny Yolanda Jacanamijoy

Mariela Pujimuy

With gratitude to the Inga Cabildo in Bogotá who welcomed us in February 2024 for the first sharing of the publication’s mockup.

Supported by the Inga indigenous peoples from Colombia, International Partnerships Office at CSM and the CSM Creativity in Action Fund.

To the Inga People of Colombia, in acknowledgment of the offerings made by everyone who participated across the territories: leaders, advisors, education delegates, and the various communities within the Inga Territorial Entity Atun Wasi Iuiai– AWAI.

More spreads and process work

More

-

Minh Le Pham

-

Central Saint Martins Shows: Graphic Communication Design | Photographed by Paul Cochran

-

Double spread. Work in progress for the forthcoming publication Inga Kaugsay / Habitar Inga / Inga Dwelling. In the image: Taita German Mojomboy, Isla Río Caquetá, Colombia. Photo: Juliana Ramírez and Roof structure, Chaclas Wasi Atarichingapa Guaruyaco, Caquetá - Colombia Photo: Musu Jacanamijoy