Everybody Phones Out is an experimental lecture series prototyped with first year students on BA Culture, Criticism and Curation. Rather than sharing a syllabus or reading list via Moodle, email or pieces of paper, Everybody Phones Out has pioneered an Instagram-based delivery system. Providing textual extracts in meme form, it seeks to simplify the learning process, whilst seamlessly integrating educational interaction into daily life.

The series is run by Elliott Burns, Jake Charles Rees and Jennifer MacLachlan, three recent graduates from MA Culture, Criticism and Curation, who are now members of the curatorial collective SPIEL. The classes are run in conjunction with Stephanie Dieckvoss and Alison Green from the Culture & Enterprise Programme.

The lectures focused on internet art post-2008. Students attended four lessons, a class trip to the Whitechapel Gallery, and the delivery of a digital curatorial project and an exhibition is to follow in May. We spoke to Elliott, Jake and Jennifer about the limitations of using Instagram as an education platform, the upcoming exhibition, and “critical savaging”.

So why Instagram? Why not Twitter or Tumblr or any other social media?

Jake Charles Rees: It’s a really interesting space; a dynamic environment where people are all doing totally different things but nobody really has a clear idea of the way that artists use Instagram.

Elliott Burns: Also, taking into account other social media platforms like Twitter, artists do show work, but maybe a Twitter project would have become more text-focussed, whereas Instagram artworks and profiles are very visual-based which links to aesthetics such as vaporwave. It’s one of the most appropriate spaces for what we’re trying to do.

How did the idea for these sessions first come about?

Jennifer MacLachlan: We were talking about post-internet art and thought that it would be quite relevant given the current exhibitions on at the Whitechapel Gallery and the Tate Modern. We were hashing out some ideas and we said well why don’t we use Instagram?

How have the sessions been going?

JCR: It’s been really interesting to break down all the layers in between a student learning about art and an artist. Obviously you have the same thing on Twitter, you can say anything to anyone you want, but when you’re having reasonably high level of discussion about the way people work and they’re able to express that straight to an artist I think that makes a really interesting space. I guess the main thing that’s been interesting is the students themselves. We’ve all learned so much from them.

What kind of things have you been doing in the lectures?

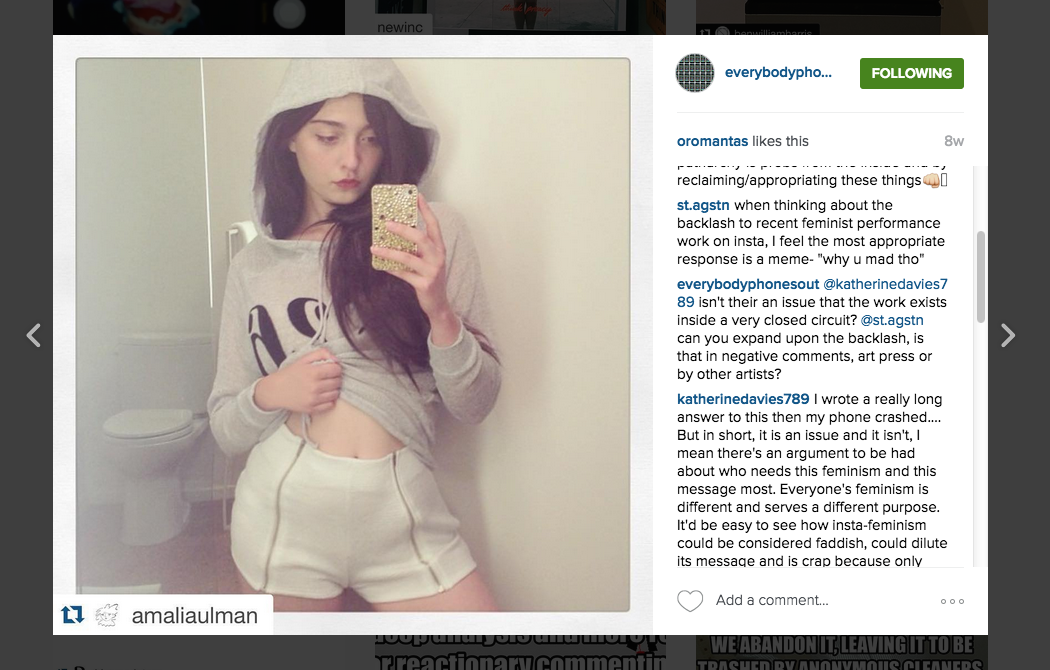

EB: So far we’ve done three sessions with them. The first looked at identity politics on Instagram. A reaction project we had them do was to pick an Instagram account and have a debate a discussion about the relevance of that artist whether or not they should be termed an artist, and the politics of what they are producing.

The second lesson actually tasked them to produce content, so they were given twenty or thirty minutes to create a visual image that they have to define along a certain aesthetic and technological production methods.

JCR: For the final lesson we took them to the Electronic Superhighway exhibition at the Whitechapel Gallery and basically critically savaged the exhibition as a group. It’s really interesting when you take a group of first year students who are certainly seeing the problems in quite a big show and responding critically to it.

EB: The students’ concerns and challenges to the exhibition were very different to ours; the kind of things that are exceedingly relevant to their generation. They read and come up with completely different ideas and values. They’ve grown up alongside this technology more than we have.

What are some examples of instances where the students have brought different ideas to the table?

EB: So the topic of feminism on Instagram for example would bring up slightly different concerns. It’s interesting seeing how they split, so some of the students would be really educated in feminist ideologies and would read it along those lines, and others would read it through celebrity culture and make it relevant to that.

What have been some of the difficulties of putting something like this together?

JCR: It turns out delivering a teaching syllabus on Instagram is a lot of work. We were practically condensing about six to ten books and two dozen articles into Instagram messages, which requires us to read those books and copy out quotes, use a huge database and translate that into digital media. While it’s been really profitable for students to have this sort of quick-fire way of digesting academic and contemporary thoughts on the matter, it’s actually a long process to set it up.

JM: We also had some difficulties with trying to get an engaging dialogue over Instagram, especially with artists. We did a lesson where the artist Ryan Trecartin was part of the lecture; we posted a piece of his video online and he liked it and he follows us now. What we would have liked to have happened was to create a little dialogue within that Instagram post and try and generate a discussion with the artist get some kind of discussion going, but that hasn’t worked out.

Why do you think that is?

JCR: I think if you have to go out on a limb publicly to make a statement about someone you don’t really understand but would like to understand, that can be quite an embarrassing or a bold thing to do. We’re asking people to use social media in a way that they’re not accustomed to. They’re not being sarcastic, they’re not being disingenuous, they are just being themselves, and that opens you up to criticism yourself.

EB: There’s been a few instances where a dialogue will start on an Instagram post between ourselves and a student or a couple of students and it can develop into something quite heavy and interesting, but it is this question of this is a very public space and so I think there is sort of reluctance for them to engage so thoroughly.

JCR: It would be interesting to try this on a different year group, to see if an MA class would be more rigorous in their contribution towards an online discussion, or whether even second years or third years or if its different courses would respond differently.

Is broadening the audience for the class something you’re planning on doing?

JCR: Yeah, we’re currently trying to design it for BA Fine Art at CSM, BA Journalism at LCC, BA Fashion Communication at LCF, and then maybe doing some short courses too. Part of this is for some research we’re doing about whether commercial technology has a place in the classroom. If you think about Moodle or Blackboard, they’re really poor ways of organising learning. The idea that they’re all open source is great, but as a bunch of curators, we don’t know how to code so we can’t make this space more interesting. I guess this is about trying to appropriate what we can use.

So do you think that social media platforms can be integrated into education contexts successfully?

JCR: I think it’s something we’d like to look at more. There’s a lot of limitations from the platforms themselves, for example if you want to footnote things that’s impossible, or if you want to put a link in there there’s no easy way unless you put a link in the bio, and then you have to change that every few days.

What would you do differently next time?

EB: I think strategising posts, timing it. There is an element of this that is very much like PR.

JCR: I do actually think we had the times quite right though. Our plan was not to do it at a regular time of the day, ever. They might get posts at breakfast; they might get them when they’re in the club on a Friday, one eye open and reading. I really like the idea that it might take you unexpectedly and that might resonate with you a little while longer.

But there’s also the fact that the aesthetic of the page is a bit of a state. There’s no coherence really, you see these blocks of memes and then you see reposts of some artists. The way Instagram organises itself is that there’s no way of bringing these things in and separating them out and making it look a bit cleaner. There’s a gallery called 15 Folds and on their Instagram they have blocks of three so you have this constant aesthetic that’s prevailing through their whole account and it makes things lot easier to engage with. There’s uniformity. When we experiment with it next time it might look a bit different.

Can you tell us a bit about the exhibition that’s going to follow?

EB: Over the Easter break we’ve asked the students to split into groups and they have three or four weeks to curate their own project. They can use any social media platform; they can create their own website; they can work across media or solely in one place. It’s really up to them how they deliver it. It can be public or private. David Gryn of Daata Editions will coming in to judge their work and select a winner. That winner will have to take their project and translate it into the physical space. We’ve negotiated a time for them to use the Vitrine Gallery at the entrance to Granary Square and it’ll be up for two or three weeks.

Finally, do you have a favourite meme?

JCR: My favourite at the moment is one of the Bernie Sanders and Hillary Clinton memes. There’s one where the issue is experimental music. It’s genius.

More information:

- Follow EPO on Instagram

- Daata Editions

- MA Culture, Criticism, and Curation course page

- BA Culture, Criticism, and Curation course page

- Culture & Enterprise Programme page