As the Lethaby Gallery exhibition exploring the connections between UAL and the Turner Prize continues, we talk to Osei Bonsu, the show’s curator and BA Culture, Criticism and Curation alum.

How did you come to the project?

"I first heard about the idea for this exhibition from Aisha Richards, founder of Shades of Noir. The challenge was to curate a show in response to UAL’s history with the Turner Prize. My proposal was related to cultural studies in the 1980s, how British artists – especially those that had gone through arts education during a time of political revolution – thought about ideas of class, race and politics.

I think there was a relentless search for a cultural identity, not simply for those groups that were marginalised, but for every artist making work in Britain during a period of social transformation. I wanted to think about those conditions in relation to the Turner Prize and the institutionalisation of British art."

In the 1980s, there was academic interest in having confrontational conversations about identity, which I felt had dropped off the intellectual agenda by the time I came to university. Through post-structural critique and cultural studies came an idea that art could confront the fundamentals questions of who we are."

Where do you begin with that history?

"I like to have an open approach towards curating. It’s a challenge with Counter Acts as we’re dealing with layers of history that go beyond each artist’s experience or version of events. History and memory are almost always irreconcilable narratives.

The more I researched, the less there was a sense of an official narrative.

Students and artists had different ideas of what University of the Arts London represented at different points in history, some had adverse relationship to the institution since graduating and felt strongly against its current formation.

There was a combination of processes for this exhibition. I went to the degree shows to look at work coming out of the individual Colleges, we also contacted art faculty to nominate students. Later on, we did our own research in the archives."

Gallery

There are just under 30 artists in the exhibition. Which pieces were you particularly pleased to bring into the gallery?

"There’s the conversation between works by Bill Woodrow and Richard Deacon. Woodrow was interested in having a dialogue about his work at St Martin's under Peter Kardia and the now-famous Locked Room project. This early narrative enriched so many practices but had a substantial impact on the early generation of British sculptors. Three of the four nominations for the first Turner Prize in 1984 were conceptual sculptors – Richard Long, Richard Deacon and Gilbert and George – though painter Malcolm Morley won.

All those conceptual sculptors had come through the pedagogic structure of St Martin’s. It’s one of the decisive moments where you can make a link between artists, what they studied and the work they went on to make. It’s a rare connection in the exhibition and establishes the ground of a dialogue between art practice and theory."

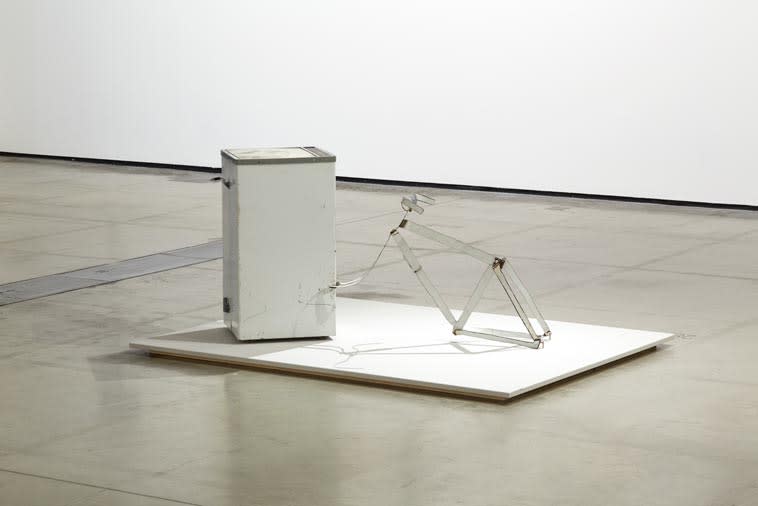

"Woodrow had started to make cut-outs, taking commonplace objects and transforming them. Woodrow was making work about the possibilities of sculpture. Opposite Woodrow in the show is Richard Deacon’s work from 1972. It registers as a conceptual performance but after this he started to make object-based work. Getting this piece was a miracle moment. Deacon knew exactly what he wanted to include and decided to participate late in the planning process.

During the research, Anne Talletire’s name came up repeatedly through people’s recommendations. I met her in her studio in East London and it was the most transformative encounter. She had a deep investment in feminism and art theory, and, together with Tina Keane, Anna Thew, Pam Skelton and Joanna Greenhill, she championed a cultural shift in British arts education. This wave of new thinking brought more experimental approaches to media, especially in terms of moving image. The fact that she and John Seth, her collaborator, taught Laure Prouvost, who’s also in the exhibition is a testament to this. These artists build on the foundations of the experimental film department established by Malcolm Le Grice at St Martin’s."

The show is about the links between education and practice. How do you show the history of the art school in a gallery that itself is within an art school?

"One of the moments that started to bring the show’s theme into focus was Nicola Tyson’s Bowie Nights at Billy’s Club. I thought they were so indicative of art school, that moment when world’s meet. You’ve got Bananarama, Billy Strange and the genesis of the New Romantic Scene. Tyson was 18 when she took those photographs. It was her first year at Chelsea College of Art. How rich to have that cultural narrative embedded in the College’s history.

There’s talk of UAL being a palimpsest of cultural and artistic life but rarely do you see it captured in photographs. These images allow us to imagine how it might have been.

Has curating the show altered your view of the Turner Prize?

"I’ve always been sceptical about prizes but as markers of artistic achievement they often do reflect the changing ideological and social attitudes towards contemporary art, which I find fascinating.

For example, Cathy de Monchaux was shortlisted for the Turner Prize in 1998. Anish Kapoor and Antony Gormley were peers of hers, but perhaps she’s not as well-known now. Her work is extremely important and has so much to say about objecthood, psychoanalysis and feminism. In Counter Acts, her work sits between the late Helen Chadwick (who was a friend of de Monchaux’s) and Alix Marie. Helen Chadwick created In the Kitchen at Chelsea College Art in 1977 during her MA. She is now considered one of the most important British artists of the latter half of the 20th century but during her lifetime she was never considered as such. Marie is a more recent graduate whose is interrogating similar questions. It’s drawing on those histories of the representation of body, sexuality and corporeality.

Presence is the key. The work on show is there for those who wish to meet it in the space. For students it could be a transformative encounter.

As it is not an institutional show, the exhibition doesn’t have to carry the weight of an institution or a prize. Just to think that a young artist might seek out a library book in connection to one of these artists or write their dissertation on one of them is enough for me."

What’s your next project?

"While working on Counter Acts I became an International Curator at Tate so it’s been a balancing act. Tate is undergoing significant transformation, so it’s exciting to be there. My focus is on African art; I have a particular responsibility to broaden and to question how artists from the continent will be represented in the gallery."

Now the exhibition is open to the public and you’re moving on, what have you taken from the experience?

"I have a sense that some of these works will survive our current moment and I will be returning to them in years to come. There is a particular set of problematics around what an art school is or could be, which I find fascinating. I am interested in the ways in which art touches society, and art schools can be a space to ask difficult questions.

"Art isn’t made in a vacuum, it always forms a dialogue with the questions of our times."

There are so many histories within Counter Acts: individual, disciplinary, institutional and pedagogic. Several exhibitions could spin out of it, but I’ll leave that for the art school students of tomorrow."

Counter Acts is at the Lethaby Gallery, 29 November 2019 – 22 January 2020. Join a lunchtime curator talk with Osei on Tuesday 21 January, 1.15-1.45pm in the gallery.