Depictions of the human body are a constant throughout art history. Artists have often turned to human forms to explore aspects of the body itself – to understand anatomy and proportion – as well as facets of our identity, both personal and societal. Here, we talk to the 2020 graduates who incorporate the body into their creative process – from performative drawing to explorations of illness.

In artistic practice, the body can be a mode and material for production as well as a subject of it. In the 1950s and 60s it became increasingly common for artists to use the body as the medium for creating work, often to question issues of gender and social codes. Working directly with the body allows artists to investigate the relationship between our interior and exterior selves. It offers up readings of the objectification of our bodies and its meaning; disorder and our societal preference for “wellness”; as well as the connections between people. It is perhaps not surprising that this year, during the coronavirus pandemic and social isolation, a wide of range of our students have turned to their own bodies as a mode of creation as well as the focus of their work.

MA Fine Art graduate Rowan Riley’s practice is concerned with bodies, illness and communicating interior, felt experience through exterior presentation: “The experience of living in one’s own body is both universal and deeply personal and not easily communicated to those around us. I have often found it frustrating that bodies seem to have a language that we can’t always access or understand – this is particularly evident when our health fails or is limited in some way.” Prior to joining Central Saint Martins, Riley trained as a dancer at Trinity Laban until she suffered a career-ending accident. “Before that, moving my body was the way I knew how to express myself” she explains.

-

Rowan Riley, MA Fine Art

Legs, 2020

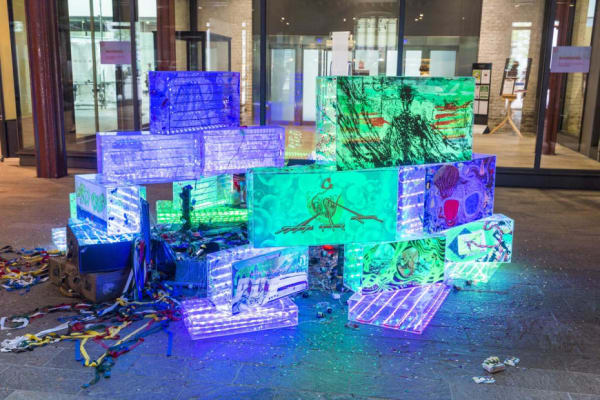

London Grads Now, Saatchi Gallery, Installation View (Photo: Heini King)

-

Rowan Riley, MA Fine Art

Legs, 2020 (Photo: Rowan Riley)

-

Rowan Riley, MA Fine Art

Legs, 2020

London Grads Now, Saatchi Gallery, Installation View (Photo: Heini King)

As part of her final graduate work, Riley produced two life-size, embroidered legs. Riley’s mark making acts as a sort of mapping across the constructed limbs, incorporating lines, words and organic forms. The legs follow a history of making human limbs and organs, beginning with hands, then a heart and lungs: “I enjoyed the challenge of working out how to create organic, personalised forms with stitching… but it became clear to me that I’m most interested in interrogating exterior surfaces. During a project last year, I met Dr Emily Mayhew, Historian in Residence at Imperial's Department of Bioengineering. Part of her role is engagement with school groups and she had worked with children on designing the perfect prosthetic. So, this is what gave me the idea of making symbolic replacement legs for my own.”

For Riley, the body's skin acts as a mask, concealing and containing our inner workings and failings:

“The body has an interior life and its exterior skin has an encapsulating protective function. Because our experience of ourselves is only our own, it’s been interesting to explore the notion of an external masking an internal truth or personal experience.”

When working on Legs, Riley did not approach embroidery as a surface adornment or encasing. Instead, “the needle passed through the fabric and caught the interior stuffing, in order for the information to be embedded within the sculpture.” The work was recently exhibited as part of London Grads Now at Saatchi Gallery.

Origin of the world, 2020

In her final project, MA Contemporary Photography; Practices and Philosophy graduate Marion Mandeng also created sculptural, human forms. Her work The origin of the world consists of 220 felt-made soft sculptures which represent vaginas. Taking its title from Gustave Courbet’s 1866 painting, the work represents both subject and object – the former referring to “the vagina as a symbol of sexual desire, while the latter is a symbol of femininity.” For Mandeng, the large number of sculptures depicts the “excessive objectification of sexuality while at the same time showing the extensiveness of sexual discrimination.” While Riley’s sculptures are concerned with externalising and exploring internal states, Mandeng’s forms are focused on the objectification of the body – something which operates purely on the exterior.

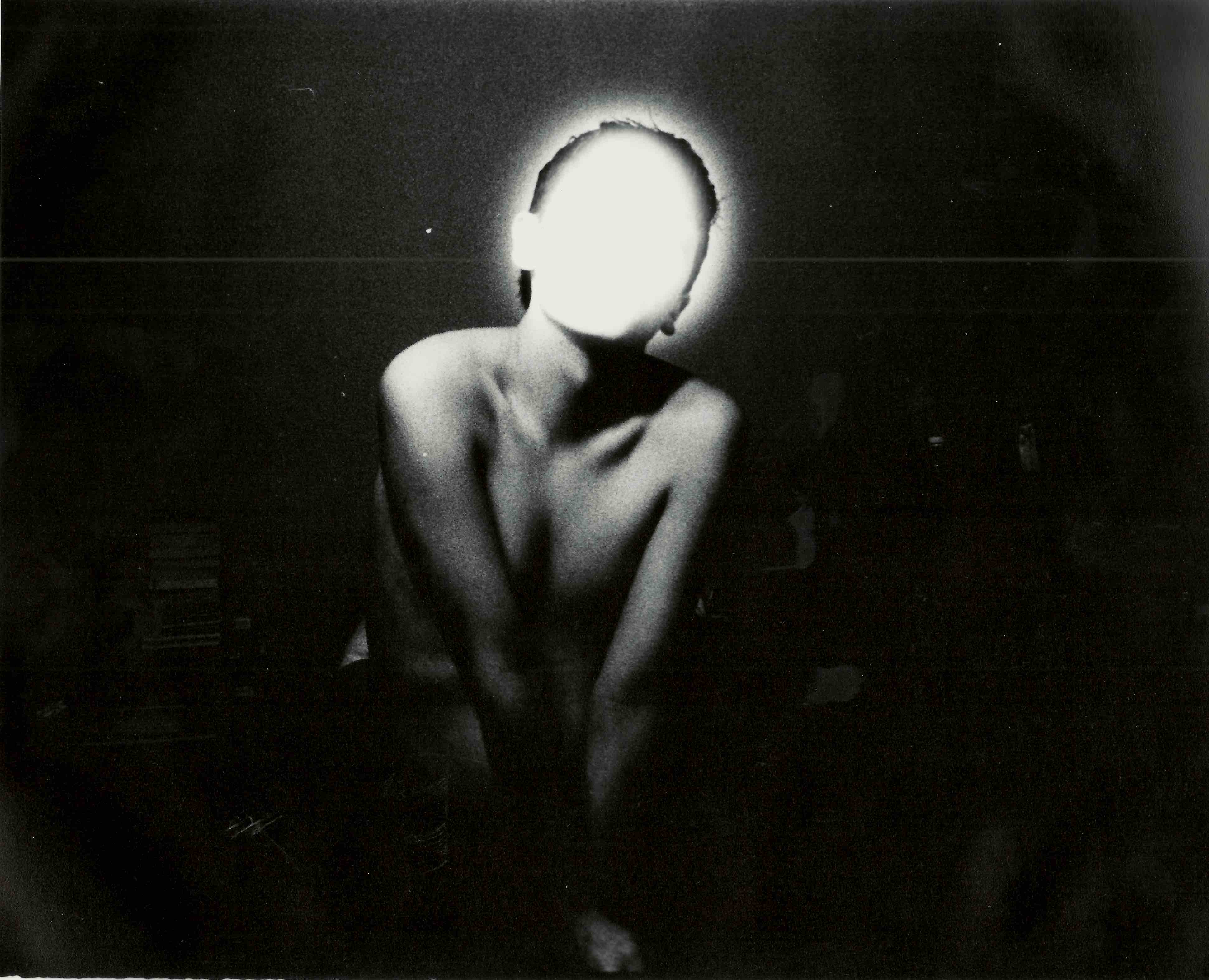

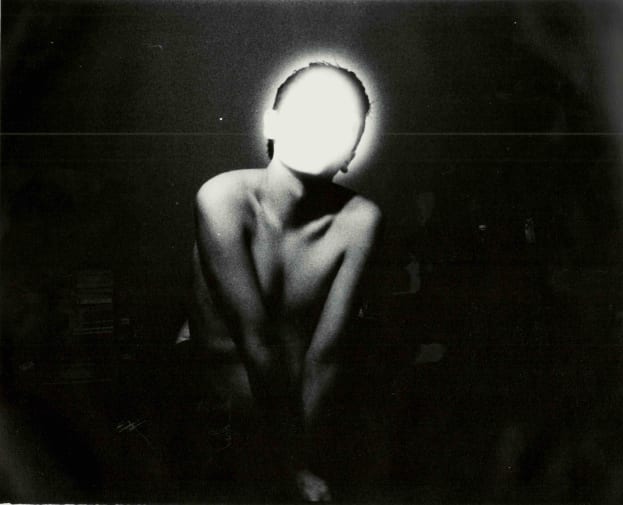

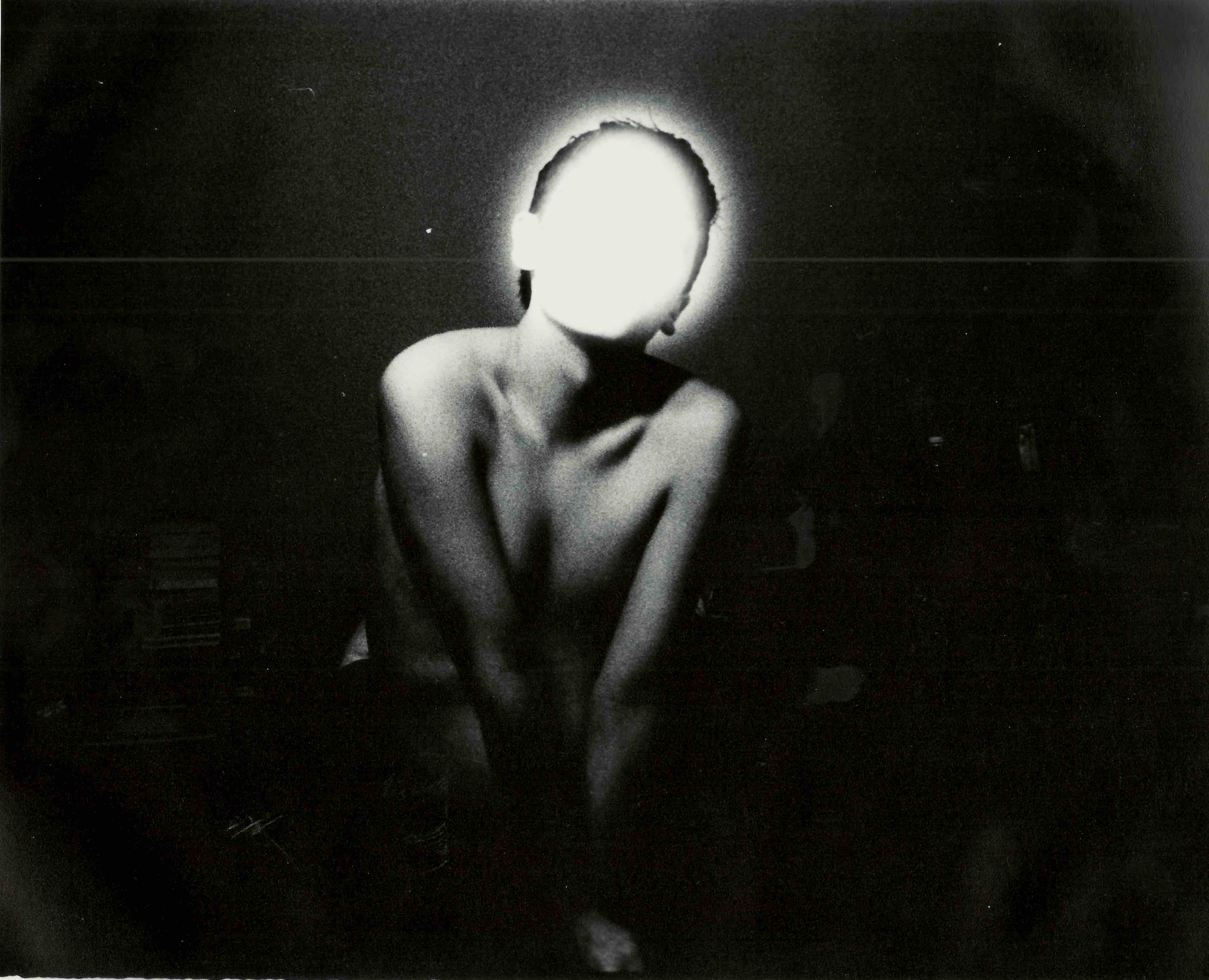

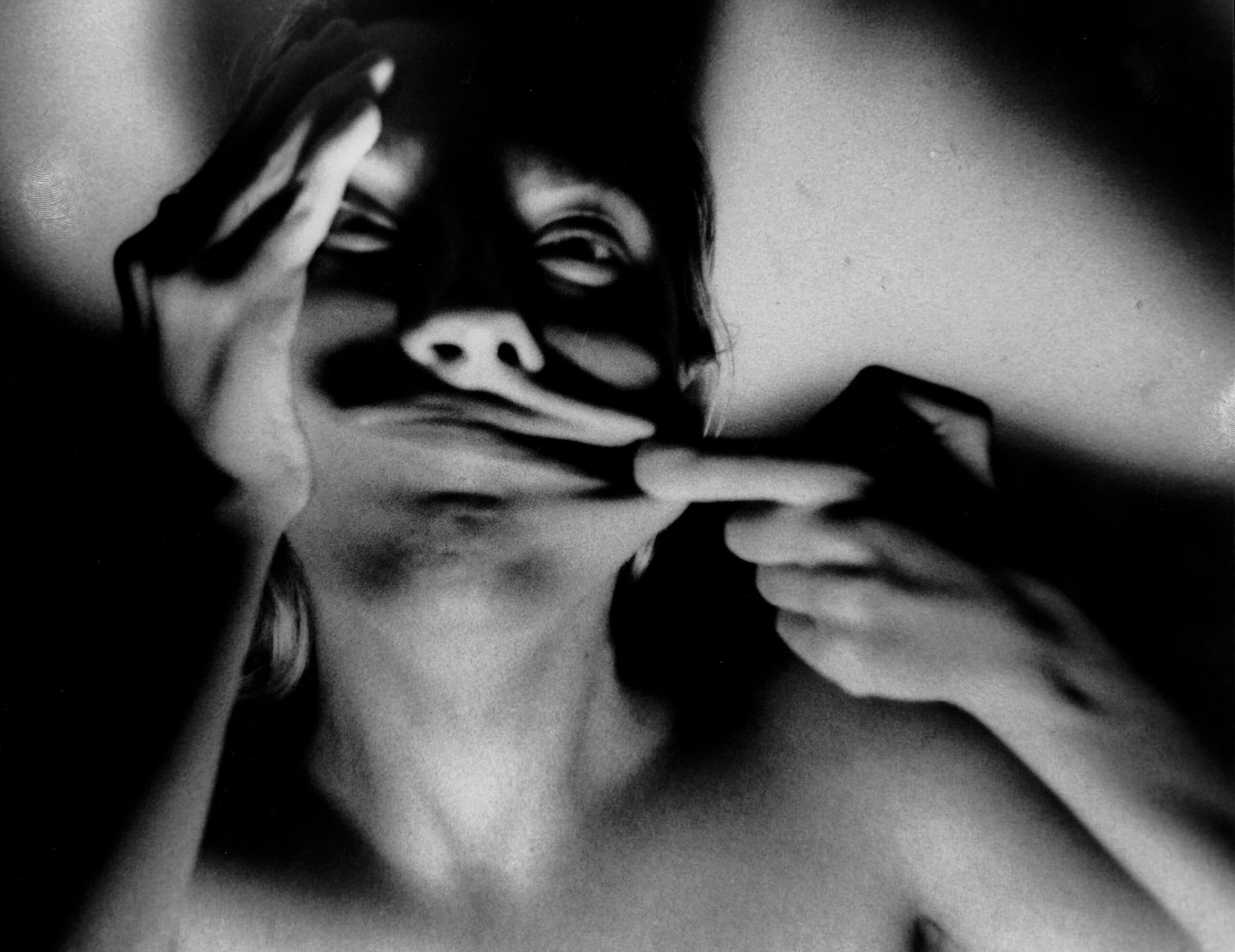

For BA Performance: Design and Practice graduate Scott Castner, the body is central to their practice, simultaneously acting as subject, tool and material: “It started from an interest in identity, but as I explored this I kept coming across new questions about bodies: how we use them, how we relate to them, how we imagine them. I didn’t really know how to address my questions about identity without first following this interest in bodies, and over time the two have blended together and become a singular interest.”

-

Scott Castner, BA Performance: Design and Practice

The Embodied Self, 2020

-

Scott Castner, BA Performance: Design and Practice

The Embodied Self, 2020

-

Scott Castner, BA Performance: Design and Practice

The Embodied Self, 2020

-

Scott Castner, BA Performance: Design and Practice

The Embodied Self, 2020

Castner’s practice comprises performance and self-portraiture – the latter of which is shot on 35mm film and developed through a number of experimental darkroom processes. In one image, Castner pulls the skin of their face in various directions, the corner of their mouth merging with the angle of their finger, the boundary of their hand melting into background shadow. In another, iterations of Castner's face are presented in ten vertical strips, fragmenting the self into multiple selves. Each self-portrait is not only a representation of the artist, but also a history of their body relating physically to itself and its records.

“I choose to shoot analogue because the process is deeply physical and I’m constantly in contact with the camera, the film, the paper, the chemicals and the light involved in the process. Rather than detaching my body from the image by translating it into pixels, I allow for mistakes, physical limitations, instincts or accidents that might not happen in a digital image. In this way, the record of these images, and what they represent about me, is altered by the continued and changing realities of my body. The process remains intertwined with the subject, so that I never have to step away from what it is I’m exploring.”

Castner approaches the mind and the body, not as separate entities, but as “symbiotic systems”. Initially drawn to ideas of binaries, they would often draw parallels between various binaries and the mind/body relationship. “Every time I added a new binary to the list, I couldn’t help but pick it apart and notice all the ways that what is happening within our bodies – sensation, hormones, digestion, pain, arousal – is intimately tied with what is happening in our minds. Instead of a Cartesian-like image of a tiny person inside my brain, I started to imagine myself as one interconnected web, bouncing information rapidly across itself and always interdependent on all the different parts.” As such, the self, for Caster, doesn’t exist in either the mind or body but rather “somewhere in between”.

Secretion Window, 2020

Secretion Window, 2020

MA Contemporary Photography graduate Laura Giesdorf also uses experimental photographic processes to explore relationships to the body. Her final project Secretion Window is a video projection in which the artist look at, licks and caresses the lens of a camera. Created during the height of social restrictions due to the pandemic, the video loop was projected onto the windows of Giesdorf’s room, visible from the street and surrounding houses. “In this work I process the loneliness and the forgetting of my own body during lockdown. Like many other people in big cities I spent months in a flat where my body only moved between three different rooms, across a few pieces of furniture, and experienced very little physical exercise. Most importantly, I didn’t experience any physical contact with others which I came to realise is what constitutes my body and my perception of it the most. Simultaneously, I developed anxiety about becoming infected by the virus. So, I was experiencing a paradox of longing for physical contact while fearing it. Secretion Window thematises this complex relationship. When the work is projected, the viewers look at my face, being intimate with the set of windows, from the inside of their houses. The glass symbolises the invisible threshold of longing for but fearing intimacy.”

Secretion Window

Laura Giesdorf

Giesdorf is interested in how, in the digital era, the body becomes increasingly fragmented by screens and displays: “I think our visual consumption of framed bodies leads to alienation of our own bodies and those of others. At the same time, the connections we create through digital devices causes the body to be excluded from the process of being together. In my practice, I use digital forms of presentation which invite the viewer in, while centring their own bodies at the core of the experience. What I find most important is connectivity of bodies as opposed to the connectivity through the internet.” In Secretion Window, Giesdorf alludes to the reciprocity of gazes between houses. The projection features close-ups of her eyes staring out from her room, watching and meeting the gaze of others caught unawares.

"This moment of revelation, of the voyeur being watched, informs the viewers that they are not isolated from each other, even if the comfort and security of their own houses and windows is keeping them protected. It is promoting togetherness, albeit in an uncanny way.”

Fenomenal, 2020

While these works unite the theme of body as subject and medium, it can also be used as a tool to create work while not being visibly present in it. MA Design graduate Olivia Barthe created her jewellery collection Fenomenal through the movement of dance. While suspended in the air, Barthe performed dance movements and drew on a piece of paper below. These drawings were then transformed into metalwork, maintaining the rhythm of her original movements. The resulting jewellery objects are an embodiment of her actions, created through the fluidity of movement – an imprint rather than a representation.

Paper Body Landscape, 2020

Similarly, MA Contemporary Photography graduate Abby Wright uses her body as a mark-making tool. She creates abstract landscapes through non-traditional drawing by placing oil pastels in-between her fingers and toes or paint on her feet. Wright's recent work is concerned with the pleasure principle and a need to transgress limits imposed on enjoyment. Her form of performative drawing allows her to play with the pleasure principle by experimenting with aspects of touch and intimacy. Across a range of disciplines, our 2020 graduates demonstrate the vast potential of the human body in artistic practice.

More:

-

Lucrezia de Fazio, Lucrezia de Fazio

-

Muneera Alsharran

-

John Arnada