by Camilla Brueton (MA Drawing, Wimbledon, alumni)

An evening exploring paleolithic visual culture and links to contemporary practice.

Professor Paul Pettitt (Durham University) gave the post-grad reading group DRAW a fascinating overview of the ‘Nature, chronology and psychology of Palaeolothic visual culture’. Chaired by Dr Kimathi Donkor and followed by Lucy George (MA Drawing) presenting ‘Hollow Chambers’ a cave-based student research project, the evening bridged ancient and contemporary drawing practice; archeology and visual culture.

Pettitt gave us a grounding in the visual outputs of the two human groups present over 200,000 years of parallel human evolution - the Homo neanderthalensi and Homo sapiens. He shared his interest and research into the psychology and physicality behind their actions; the intent, the physical relationship between the person, the cave, their society and the visual outcome.

Paleolithic art survives in the cool and stable conditions of deep caves as wall paintings or small objects (tools or non -functional items); the lack microbiological erosion favouring preservation. It can be non-figurative and figurative – mostly images of prey animals, mostly disconnected from the landscape.

Challenging our stereotype of early humans – that of an unsophisticated ‘cave man’ making drawings for magical purposes, Pettitt encouraged us to think about how Homo sapiens and Homo neanderthalensi had flourished. Their actions justifying the extra-large brains they possessed in relation to their body size and the expensive metabolic outlay these brains required.

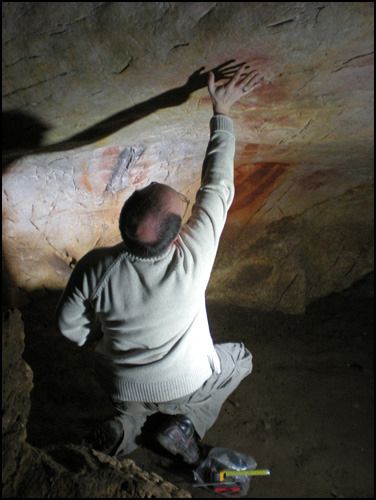

Pettitt suggested non-figurative cave paintings could be intentional expressions of a physical relationship with the cave. Marks (daubs or stencils made using pigment) are often found at the extremities of underground spaces. These aren’t random and have been made with considerable effort. Hand stencils or daubs appear along a ridge, inside a crevice, up high, down low - a visual mark of a physical encounter between the cavern and the body. Pigment was daubed or spat, sometimes over a hand creating a stenciled outline on the cave wall.

Hand Stencils

Pettitt has developed a theory that these hand stencils could be a bridge between non-figurative and figurative works; seeing an outline around a hand, led to the creation of outlines of other things. 37,000 years before present (BP), figurative work by neanderthals began to appear – animal outlines painted in caves and as carvings on objects. From 32,000 BP onwards, the dominance of animal depictions prevails. The context changes, perspective is introduced. Animals have movement, landscape is sometimes present. Different groups display different ‘art schools of thought’ in their style and approach to image making. The subjects of hunting, reproduction, birth - the images of the rutting calendar of their prey dominate.

Pettitt talked about the psychological triggers we have- and the importance of natural shape and shadow in the understanding of early art. Just as we can stare at a cloud and see an eagle, cave art responded to forms already there- a horse’s head drawn to the shape of the edge of a wall, a buffalo made from a freestanding rock, when lit projects its shadow onto the cave wall behind. Pettitt described how sophisticated mark makers cave people were:

"Sometimes just enough was carved, the dome of a head, the shape of a back and you know you were dealing with a wooly mammoth"

P. Pettit

Pettitt also emphasized their spatial awareness; the deliberate use of cave topography to suggest animals were running, adding drama.

Asked if these caves were lived in, Pettitt explained that where daylight dies, so do we. Cave mouths were inhabited, but cave systems stretching miles into the darkness weren’t. But they were explored and marked. Cave paintings have been found 6 miles in -with lighting reliant on candles made from fat, this must have taken considerable supplies, effort and dedication. Candle light is ever shifting, adding to the liminality of the space; casting shadows that perform. Caves in mythology are a bridge between this world and the next, with slippage through the cracks and fissures, expanding in the darkness.

But is it art?

“In all small-scale societies, art has a function.”

P. Pettit

Cave paintings took considerable effort, often by more than one person, suggesting they were invested in by society. They seem to have been collaborative and performative in execution and experience. Pettitt’s presentation crafted a hypothesis that Palaeolothic visual culture grew out of a long tradition of body centred art, with brains geared towards thinking about animals and the space of caves acting as a hyper trigger, the hand stencils acting as a bridge between non-figurative and figurative representation.

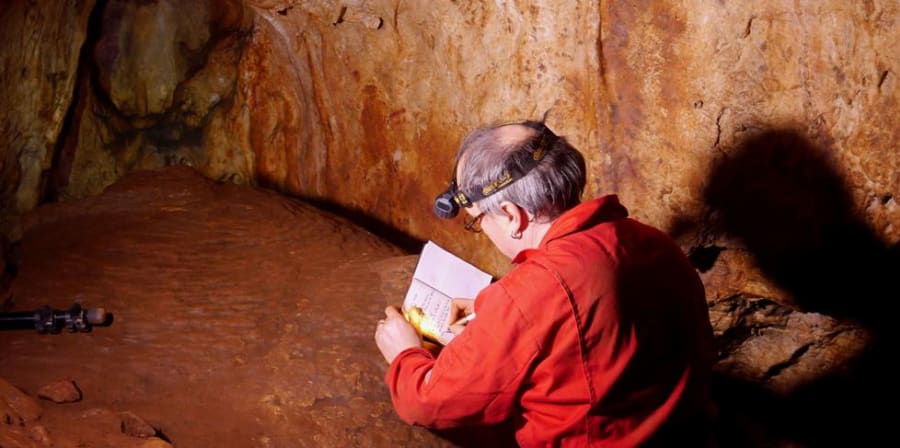

Caves are being explored as a site for making and inspiring work by 4 MA students at Wimbledon College of Arts. Following Professor Pettitt’s presentation, Lucy George (MA Drawing) spoke about “Hollow Chambers”; a recent two day residency in the Goatchurch cavern in Cheddar Gorge and a forthcoming exhibition. Subjects explored included: the ecology of the cave, drawing in the dark, exploring surface and structure, the memory of water, body-mind methodology and the re-enactment of memories, triggered by the cave environment.

After the presentations, Dr Kimathi Donkor articulately asked Professor Pettitt:

“Modern culture sees cave people as inferior, yet we are in awe of their drawings. Can you repair their reputation?”

Dr Kimathi Donkor

Pettitt responded by quoting an early archeologist’s description of cave paintings as ‘the infancy of art, not the art of an infant’ and went on to suggest it is possible cave people had complex belief systems, but simple art outputs. Like the MA students in Hollow Chambers, they engaged with the multisensory environment of the cave – a tactile experience. We have the same brains as our early ancestors.

This evening highlighted a connection between the Paleolithic and the production of visual culture today. Spatial concerns and performance, an obsession with animals and food are still current; think YouTube videos of kittens and Instagram pictures of food. Whilst most of us don’t hunt, we are still obsessed with animals and pictures of what we eat. How and why we produce visual work, the methods we use to reflect on what is important to us and our tradition of mark making can be traced back to pigment being spat on a wall and a collaborative embodied way of working as a result of a physical response to our surroundings.

Hollow Chambers the exhibition will be taking place at the Crypt Gallery, 5-11 March 2019

For more information, email hollowchambersproject@gmail.com

This DRAW event was organised in collaboration with Silvia De Giorgi and Denise Poote, MA Drawing students at Wimbledon College of Arts.

DRAW is a postgraduate reading group focusing on interdisciplinary approaches to drawing.

It hosts events each term, and is a pan UAL initiative, funded by the Post-Grad Community.

DRAW events are open to all UAL Postgraduate Students, UAL staff, as well as a wider community of invited alumni, practitioners and researchers in the field. Email pgcommunity@arts.ac.uk to join the mailing list.