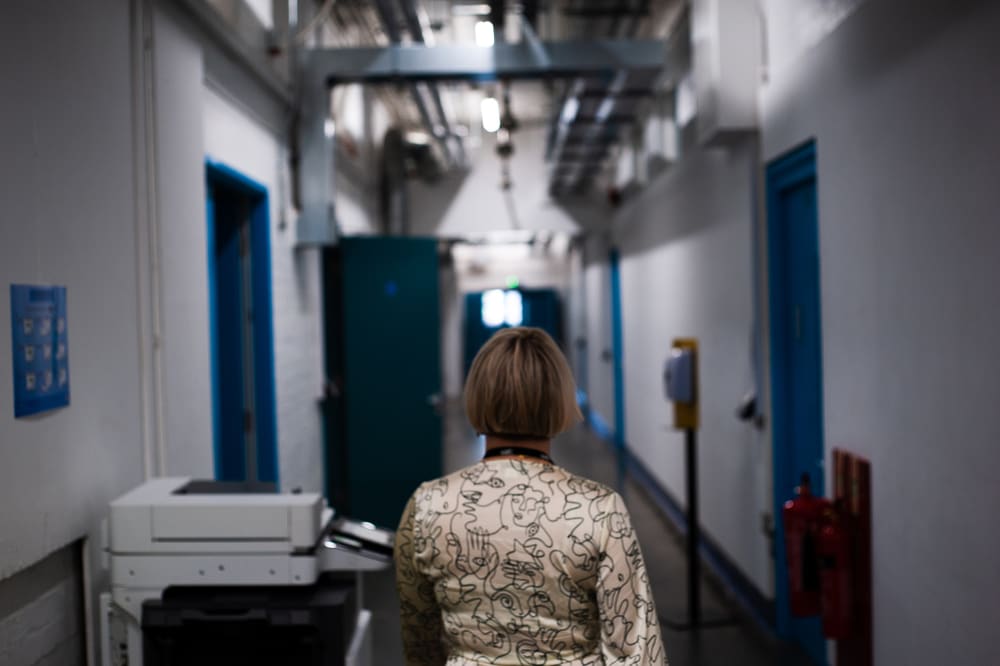

, Wimbledon College of Arts, UAL | Photograph: Samin Shirazi-Kia

Award-winning writer and academic Dr Katie Beswick has recently been appointed Acting and Performance Programme Director at Wimbledon College of Arts.

Following a varied career which has taken her from being barmaid to performer, and housing officer to scholar - with more in between - her work comprises a dynamic mixture of form and content. Through journalism, creative writing and scholarship, Katie assesses and approaches class, performance and culture, deciphering tradition and history with fresh insight.

Born in south east London, Katie became attracted to community drama early on in life. She eventually found herself undergoing performance training at a conservatoire. Her experiences at the conservatoire brought to the fore ideas that had been simmering since childhood, and following new perspectives gained working in a London Council, she decided to become an academic.

Speaking to External Communications Coordinator Samin Shirazi-Kia, Katie tells us in her own words about her history and what drives her.

I have been interested in performance since I was a small child. My route to theatre was mainly through community arts and education practices, and being exposed to drama through primary school. In those days, we didn't have a national curriculum so our teacher would come up with a topic and ask us to design a big space and I always found that really exciting.

I was always a loud, outgoing child, so I was drawn to that kind of thing. In my teens I got involved in community drama in London, where there were lots of young people’s theatres, which were a hangover from the community arts movement in the 1970s. I used to go to weekly community theatre and drama groups which were all about ensemble, non-hierarchical practices. I wouldn't have necessarily called it that back then, but that is what we did. We'd make our plays based around themes, and we'd work together, playing games.

I grew up in a working-class community in London. In south east London the clubs weren't very expensive, so they were open to everyone, and were really diverse. You had all sorts of different types of people, in terms of race, class, that kind of thing, which felt exciting. The whole time I was doing drama at school, and then did a degree at university. When I came out of university I then did an MA in actor training at a conservatoire, and then when I left there, I set up a theatre company. I also worked in housing for a London council.

I've always been interested in issues of class because of growing up where I did, and then I went to a Russell Group university, and it was always known as a really posh university. I went from an environment where I had been possibly the poshest person in my school – as in my parents owned their house, and we didn't live on an estate – to going to a university where I was exposed to a very upper-class culture and people, which raised a lot of questions in my head about class, politics.

In the early 2000s, the discourse around class had fallen out of fashion. The curriculum I was studying on a drama degree was very much about historical texts and ensemble devised community practices, but we didn't ever look at the sort of social, political roots of where those practices had come from.

Throughout my career in drama, issues of class were always bubbling up, and when I came to a conservatoire, this became very stark. At a conservatoire they're training you to be a certain kind of actor, so questions about what you are most likely to be cast as – people's perception of you as a person – suddenly became really stark. I remember at university one of my teachers said something to me like "you're just council estate, and that's all you'll ever be". This shocked me, since I was on a council estate as a baby but didn't grow up one. It was an odd thing to say.

I ended up getting a temp job in housing which I found very interesting, and while I was doing that, questions and issues of class politics came up again, as I was working in Hackney on council estates there, so I ended up doing a PhD which was in Theatre but was looking at council estate performance practices.

If you say the word 'council estate' to anyone in England, they have an image in their mind – whoever they are – and there is a set of ideas based around it, so I was interested in how the things we see in cultural performances – on stage, television, film – feed into our understanding of what an estate is, and how spaces kind of work in relationship to performance.

No, I initially wanted to be a performer. I was always a very academic person, I've always been interested in thinking critically about social concerns and culture issues, so it made sense for me to do an academic drama degree, rather than conservatoire training. And then when I did go to do conservatoire training, the experience destroyed my love for performing.

There is a culture of conservatoire training which I think has historically been quite abusive and has been hinged on unequal power relationships that disempower the student. Particularly, students from non-traditional backgrounds – black and ethnic minorities, working class students and female students – have experienced all sorts of abuses of power which have come out in the press in the last few years. That was definitely my experience of a conservatoire. On leaving the conservatoire, I experienced really bad stage fright, and often felt sick on the stage.

Yes, but I didn’t at the time. I didn't know what was causing it, but I knew that I was enjoying it less and less. At the same time, I had questions about class politics that had been under the surface of my experience of theatre, but I never had a forum to discuss them.

At university we had had to write a final essay called Theatre Praxis, which is about how your political and ideological position shapes your practice. I was trying to write about coming from a culture of the working class, and a family that had been working class historically, and how coming into a really elite university had shaped my practice. But at the time I hadn't been introduced to any of the class literature, or had any framework to really talk about that stuff. I got a really bad mark for that essay! But I now look back and think, what I've been trying to do for the rest of my career is write that essay.

Once I realised I could no longer perform anymore, and it was actually making me quite unwell, I decided that I wanted to do a PhD. I felt the only way I could find answers to the questions I was asking was through studying some more. I did have a brief career doing some corporate films, some short films, a little bit of fringe theatre, so I was performing after I left the conservatoire, but it was becoming less and less important. I was finding other avenues to creatively explore the issues I had, and theatre wasn't working for me as a forum in which to explore those things.

I applied for this role because what is happening at Wimbledon is a response to the landscape of performer training that I described in my personal experience. Over the last few years there's been a lot of public activism by students, and there's been a lot of public discourse around conservatoire training and actor training. I've always had an interest in performer training and political inequalities embodied in that.

I am very interested in what Wimbledon is trying to do, which is a new model of actor training through the philosophy of an art school. If conservatoire training is about preparing an actor for industry through intensive full-time training, then an art school is about allowing artists to develop themselves as individual practitioners. Obviously, you work alongside other people, because that's what theatre is, but in ways that feel true to them, and will allow them to have their unique set of practices.

This is a place where people can really begin within themselves, rather than starting from an idea of what the industry wants. It's about creating people who will shape and innovate that industry.