My name is Cat Kerr, and I am currently studying on the Goldsmiths MA Queer History. I am currently completing a placement, jointly organised between the Goldsmiths MA Queer History and University of the Arts London (UAL) Archives and Special Collections Centre (ASCC).

I applied for this placement in the winter of 2023 due to an interest in gaining practical experience alongside my master's degree in queer history. A large part of my degree has been not just the study of LGBTQ+ history, but the queering of history itself. Through this placement, I was eager to explore how this concept could manifest in practice through ‘queering the archive’.

Throughout this placement, the question I held in my mind and have tried to respond to is: what does a queer archive look like? What are queer archival practices?

As I’ve come to learn, both in my degree and in my placement, queer history has often been thought of as a hidden history. It has typically been nestled away in criminal records and official documents. There it waits to be carefully extracted by historians. The amount of readily available information about queer stories is harder to hunt down than mainstream histories.

In modern UK history alone, queer people have faced multiple persecutions. Most significant are criminalisation, the HIV/AIDS epidemic, and more recently, Section 28. These events have affected the information available on queer lives and histories. Some information has been lost or destroyed. Some information was never documented in the first place due to fears of legal persecution or ostracism.

My role within UAL ASCC has focused on two of their archives: the Cockpit Gallery Archive and the Camerawork Archive. They feature two radical photography organisations operating throughout the 1980s and 1990s. As part of my placement, I drafted nine authority records about nine different contributors within these archives.

For background, ‘authority records’ are searchable by researchers via our online archives catalogue. They help provide additional context to archival material by providing information about the people and organisations who created or contributed to the material. This context can be especially important when dealing with people or organisations where less material has been kept or made available.

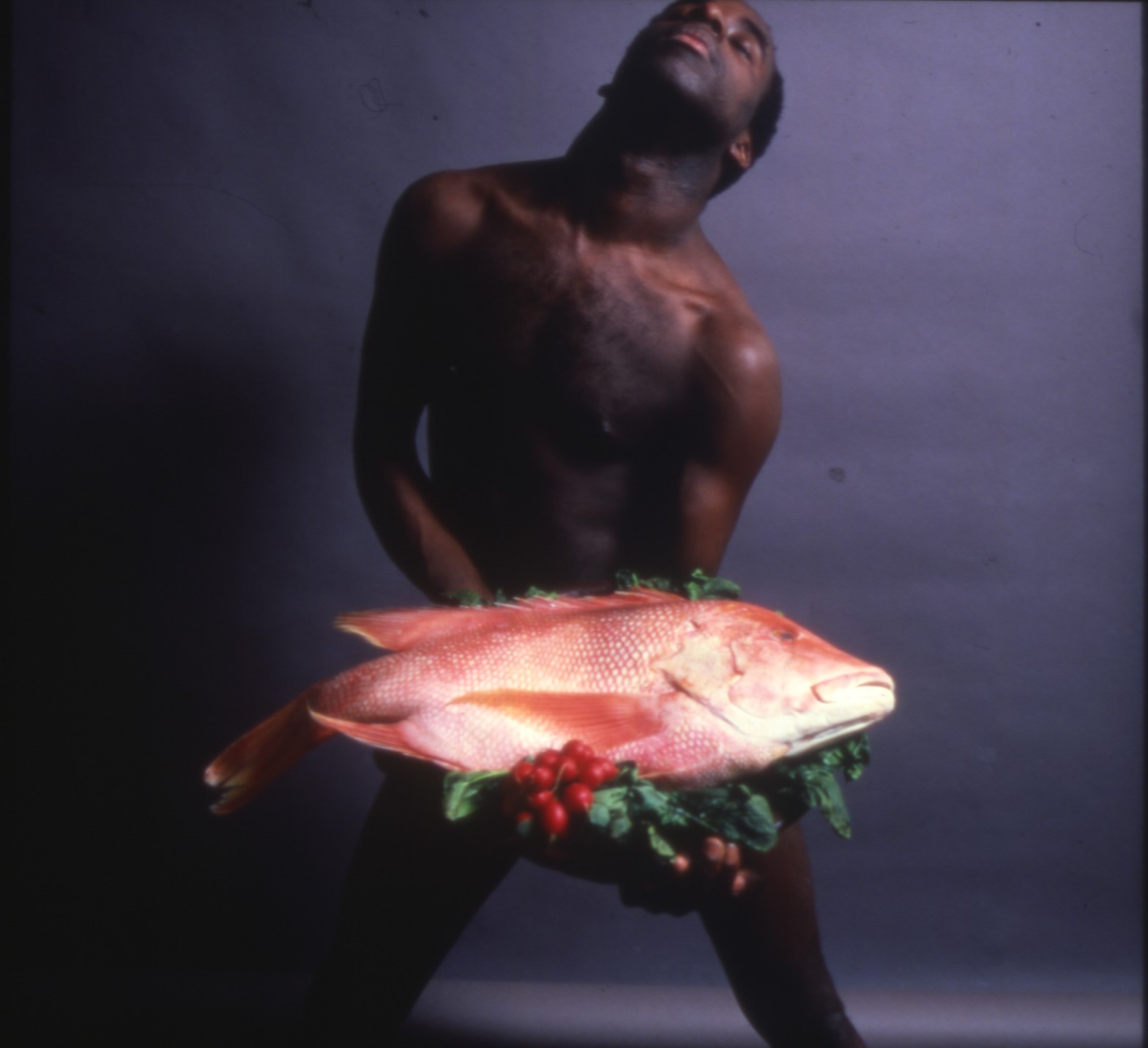

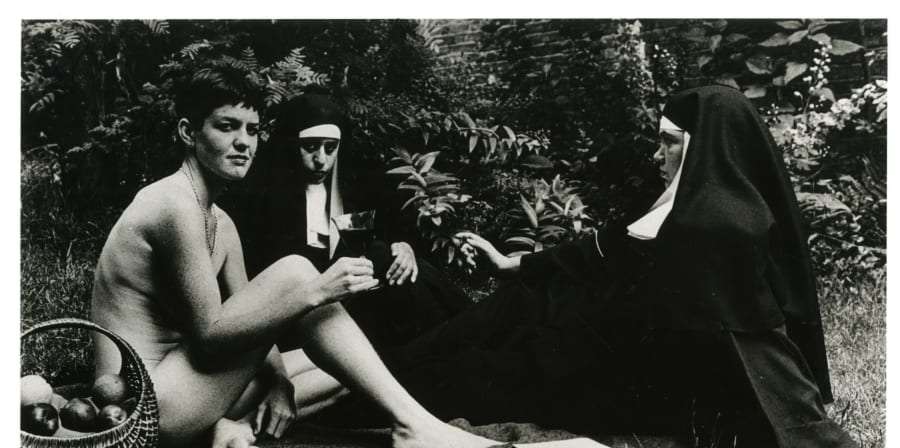

I looked at three Camerawork exhibitions in my work. From Bodies of Experience (1989-1990), I researched Rotimi Fani-Kayode and his partner and collaborator Alex Hirst. From Partners in Crime (1989) I looked into Sunil Gupta. And from Stolen Glances (1992) I focused on Tessa Boffin, Deborah Bright, Jean Fraser, Del LaGrace Volcano, Mumtaz Karimjee and Jill Posener. Additionally, I drafted an authority record for Rosy Martin who was involved in Cockpit Gallery exhibitions. These artists all contributed to queer photography exhibitions and were queer themselves. From my experience drafting these authority records I set off figuring out how to consolidate my research into a queer public history project.

The photographers involved have already archived their own personal experiences with queerness. Tessa Boffin used elements of surrealism and fantasy to solidify lesbian identities and critique mainstream attitudes towards the HIV/AIDS crisis. Rotimi Fani-Kayode and his partner and collaborator Alex Hirst used photography in response to the HIV/AIDS crisis. Their work draws from African notions of healing. Jean Fraser queers Christianity through her photograph of a naked lesbian sharing a glass of wine with a pair of nuns. These artists have preserved their own queerness through photography. Now it is up to the archive to continue this.

Through my research process, I found it could often be a struggle mining the internet and the library for biographical information. How could I counter the issue of representation in the archive, when there was so little information to go off? I was mindful that to a future researcher, this lack of information could be read as a lack of effort or care towards authority records for members of the LGBTQ+ community. I wanted the biographies I created to be as rigorous and detailed as the authority records elsewhere in the UAL archives.

Perhaps a queer archive is a self-conscious one, aware of its limitations, constantly growing and evolving. After discussions with my placement supervisors, we thought of ways we could acknowledge the lack of information and do a call-out for more, a sort of crowdsourcing, a search for community knowledge so these individuals could be memorialised justly.

I played around with phrasing and structure, and settled on a potential phrase such as ‘Our archive is ever expanding, and we’re always on the hunt for more information’. Therefore, an acknowledgement of our own limitation is stated, alongside a method to rectify this. It feels like a step in the right direction to fight the otherwise default erasure of queer lives in the archives.

During the creation of my authority records, I was always aware of how different this form of research was to academic writing. In academia, every fact must be referenced alongside certain guidelines – for myself I must add a footnote with citational information, as well as a bibliography.

Within my authority records I didn't have to follow this strict protocol, which prompted me to think about the ethics of creating authority records. Who has the authority over the facts of someone's life? To have control within an archive is to have control of what is remembered and how it is remembered. Archives are often imbedded within and regulated through hegemonic power structures. It felt like a lot of responsibility to try and counteract these structures.

I remained conscious of the political impact of the information I was choosing to preserve. Where available this was every fact, date, and story I could find. To document and preserve the lives of queer people is a queer act. Fighting the systematic erasure that queer lives have been subjected to for a large part of history is an act of activism.

Another step I took to counter the authority of the archivist, as well as find out more biographical information, was through, where possible, contacting the artists I was researching. It gave them the chance to add, remove, or change the biographical information I had written. This felt like the power was being handed back over, making the individual not just a passive object within the archives, but an autonomous participant. To subvert power relations and challenge authority in this way is another way to queer the archive.

The artists found within the Cockpit Gallery Archive and Camerawork Archive were documenting their own queerness as a form of resistance primarily to Section 28. And now the ASCC is continuing their activism through preserving their work for future researchers.

Further reading:

Donnelly, Sue, ‘Coming Out in the Archives: The Hall-Carpenter Archives as the London School of Economics’, History Workshop Journal, 66.1 (2008) pp. 180-184.

Flinn, Andrew, Stevens, Mary, ‘’It is noh mistri, wi mekin histri.’ Telling Our Own Story: Independant and Community Archives in the UK, Challenging and Subverting the Mainstream’, Community Archives, eds. Jeanette Allis Bastian, Ben Alexander (London: Facet Publishing, 2009) pp. 3-27.

Macleod, Suzanne, Sandell, Richard, Cowan, Sharon, Scott, E-J, Cuzzola, Cesare, Plumb, Sarah, Trans-Inclusive Culture: Guidance on Advancing Trans Inclusion for Museums, Galleries, Archives, and Heritage Organisations, (Leicester, Research Centre for Museums and Galleries: 2023).

Nestle, Joan, ‘The Will to Remember’, Journal of Homosexuality, 34.3 (1998) pp. 225 – 235.

Selsdon, Helen, ‘Creating a Fully Accessible Helen Keller Archive’, in Crip Authorship: Disability as Method, eds Mills, Mara, Sanchez, Rebecca (New York: New York University Press, 2023) pp. 170-177.

Schwartz, Joan M., Cook, Terry, ‘Archives, Records and Power: The Making of Modern Memory’, Archival Science, 2 (2002) pp. 1-19.

Wakimoto, Diana K., ‘Archivist as Activist: Lessons from Three Queer Community Archives in California’, Archival Science, 13 (2013) pp. 293-316.

X, Ajamu, ‘Love and Lubrication in the Archives, or rukus!: A Black Queer Archive for the United Kingdom’, Archivaria, 68 (2009) pp. 271-290.

Yaco, Sonia, ‘Historians, Archivists, and Social Activism: Benefits and Costs’, Archival Science, 13 (2013) pp. 253-272

Questions?

For any questions about UAL Archives and Special Collections, please email archive-enquiries@arts.ac.uk