Jane Murrow, Chelsea MA Textile Design Course Leader, shares her thoughts on fashion's sustainability problem.

Where to begin?

There are numerous, multi-layered issues. Complex long-established systems along with the eye-wateringly vast investment and the lengthy periods needed to develop and shift to new technologies. On top of that, profit-led business models, supply chains and price structures add to the complexity.

Taken together, this is fashion’s sustainability problem - and the industry is the proverbial rabbit caught in the headlights.

It doesn’t know how to do what it knows it must do, without up-ending it’s entire modus operandi. There are numerous brands, new and old whose ethos ad models are built around sustainable, ethical products and, the will to make change across the industry is increasingly there - but as a whole, it is currently stuck, tinkering around the edges, or making grand pledges and promises that have yet to be fulfilled.

How did we get here?

Has the industry unwittingly landed in a predicament largely of its own making - itself now falling victim to a system it’s long benefited from?

The majority of current fashion business models have been developed over decades with the central raison d'être being to increase profits by ‘selling more stuff’. This leaves the entire industry with a fundamental and existential dilemma that is diametrically opposed to the need for urgent systemic change, including a massive reduction in per capita clothing consumption.

The consumer is frequently blamed for having expectations of unrealistically low prices, but let’s not forget that cheap clothing (which in real terms, has spiraled downwards over the last 20 years), has been driven by the retail industry’s own desire to sell ever more units.

There is an egalitarian side to this; mass-production and affordability has made a much wider range of clothing and choice available to virtually all, instead of only to those able to afford it. Equally, are we not all guilty of having bought into this by making clothing choices based on low prices and affordability, regardless of our budget? We all have a role and a responsibility in creating, and now fixing this mess.

However, when retail profit margins are shaved to lure customers with irresistibly affordable prices, the costs in every sense, are borne by the fibre, fabric and garment producers and suppliers, in turn driving down workers wages, incentivising land use for often pesticide-ridden fibre crops over food production in some of the poorest areas of the globe and encouraging (effectively forcing) manufacturers to seek the cheapest possible methods, often resulting in corner-cutting on, for example chemical use and emissions, and a disregard for safe working conditions - the effects of which are now affecting us all as we tumble into climate emergency.

Why are we stuck here?

Vastly cleaner, greener technologies and the ability to re/up-cycle fibres and materials appear to offer one of the best solutions for the industry, allowing continued mass-production (and high consumption with a growing global population) whilst dramatically reducing the environmental impact.

However, there remains resistance and/or inability to invest the billions of dollars needed globally to make the necessary seismic shift. It also requires the many players and stakeholders in this complex and highly competitive industry to collaborate by sharing both new technologies and the investment burden, which is needless to say, problematic.

Many new and emerging technologies exist but aside from massive investment, they often take years to test and scale - and are then often (and understandably) patented by those who have made the large initial investments, becoming exclusive and prohibitively expensive - when altruistic, open-sourcing is what is actually needed.

Internationally-binding and enforced legislation on a global scale seems the only likely means by which to compel all sectors of the industry to act, but without global consensus, cheap production will only move to zones where laws do not apply. This risks decimating current manufacturing communities (often in already poor regions) and devastating humanitarian crises, rather than improving technologies, production practices and working conditions.

It is also surely the lower end of the mass-market that faces the greatest challenge to make the necessary shifts, as they have the least room for manoeuvre on margin, relying instead on turning over very high units.

Progress is being made and the pace of change is gathering speed, but it remains to be seen if change can happen fast enough and effectively enough to limit climate change measurably without destabilising the production systems that millions of workers rely on to survive.

What to do?

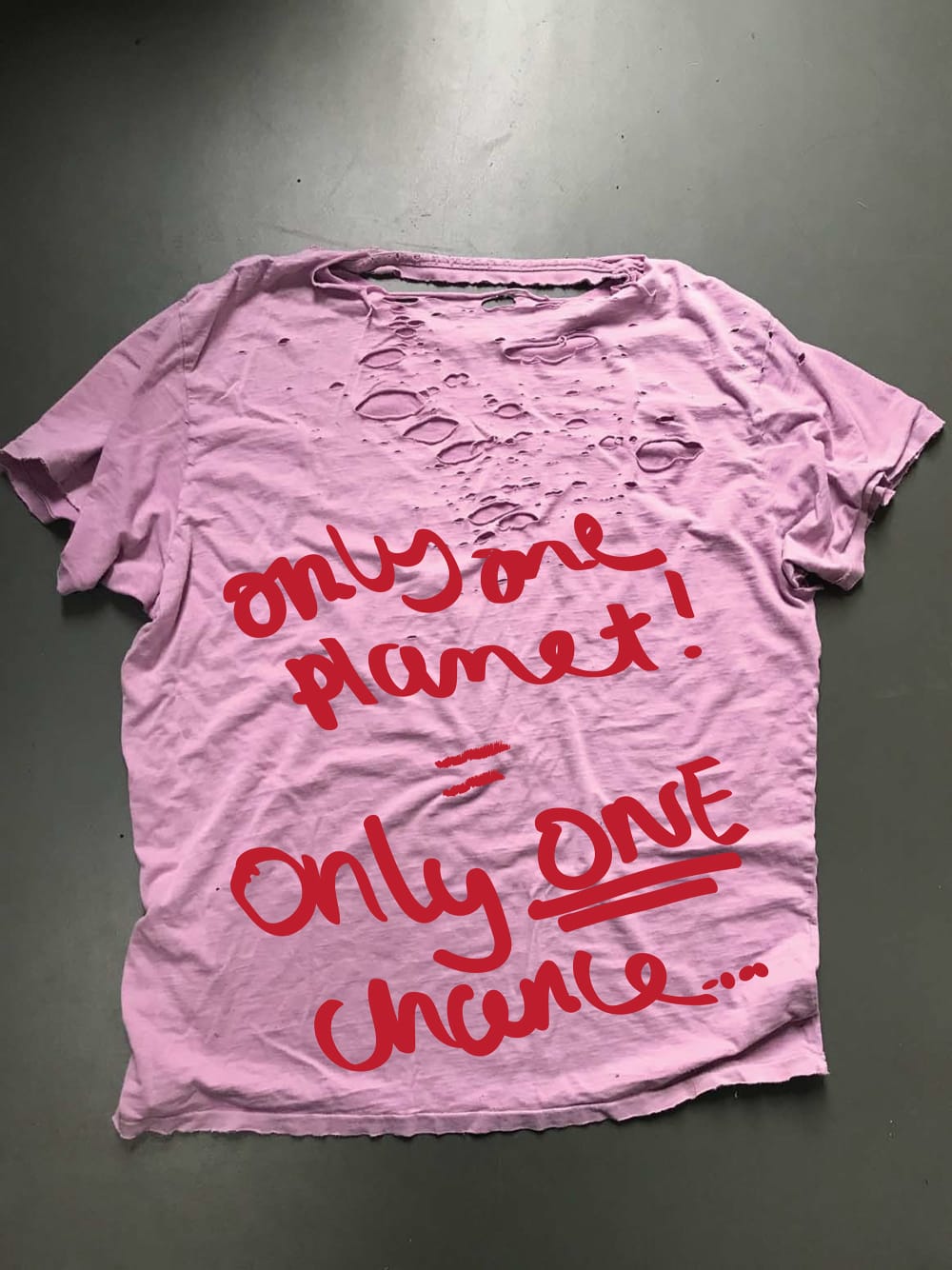

It’s not all doom and gloom and the ‘Greta effect’.

Growing public awareness (and increasingly, direct experience) of climate crisis is effecting rapid change in consumer attitudes and expectations. Herein perhaps, lies a very ‘consumerist’ element to the solution via the old adage “the customer is always right”: companies that fail to keep pace and resonate with their customers weaken and may ultimately fail. People around the world, particularly the young, are demanding drastic and immediate action from their governments, which trickles down to them demanding information and transparency about their clothing, driven by a desire to make informed, ethically and environmentally sound purchasing choices – we want to buy ‘better’.

This can only be a good thing and probably the strongest incentive of all for companies to improve their practices, invest in new technologies and radically update their business models in order to survive.

Neither must it be forgotten that we as players in the industry: designers, consultants, buyers, marketing managers, through to manufacturers, shareholders and business owners, are also consumers and citizens of our badly-injured planet are in the face of climate crisis, also demanding and exacting behavioral and systemic change from within.

We are all in this together.

Find out more about MA Textile Design at Chelsea College of Arts.