The story behind the Edward Reeves Archive project

- Written byHannah Mayall

- Published date 20 July 2022

Lewes, in East Sussex, is home to the world’s oldest photographic studio — Edward Reeves Photography. Still active and operated by direct descendants of the founder, four generations of Reeves photographers have encapsulated the stories of the inhabitants of this English market town since its establishment in 1855. The current owner, Tom Reeves, now runs the Studio, still located on Lewes' High Street, with his wife Tania Osband. Together, they continue to add to its legacy.

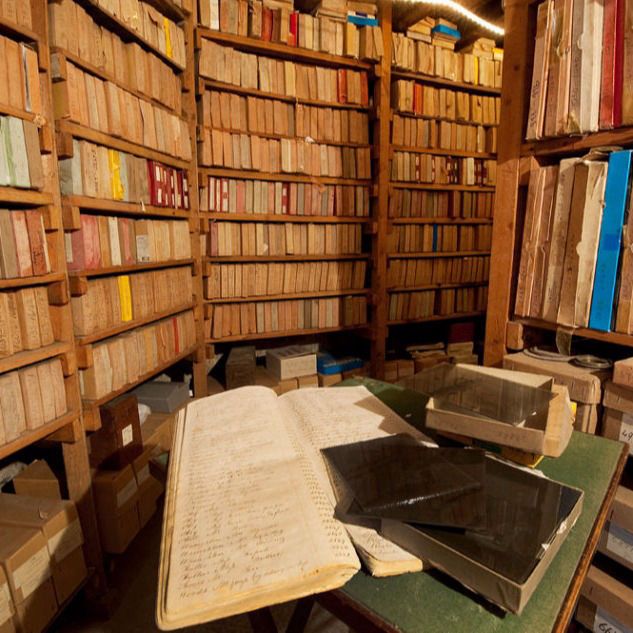

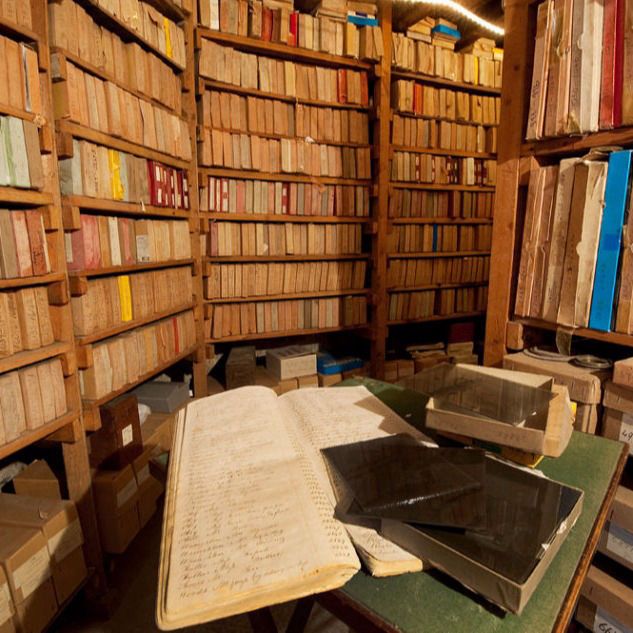

As well as still being fully operational, with original back grounds and furniture, the Studio also houses approximately 200,000 glass plates and a similar number of negatives on film and in digital format. Most importantly, much of the corresponding paperwork has also survived. This previously untouched archive documents the life of the people of Lewes, and the town itself throughout some poignant events in British history and is an important source of knowledge about the development of commercial photography.

In 2013, Brigitte Lardinois, Director of the Photography and the Archive Research Centre (PARC) based at London College of Communication, met Tom and Tania whilst researching a book about the nearby Glyndebourne Opera House. The meeting introduced Brigitte, back then a Research Fellow at LCC and previously Cultural Director at Magnum Photos and Exhibition Curator at the Barbican Art Gallery, to the Studio's extensive collection. This encounter opened up the possibility of establishing a collaborative research project with the Reeves Archive.

An insight into the Edward Reeves family photography business.

Videographer: Abigail Norris (2015).

The project started in earnest in 2014 and soon the true extent and uniqueness of the archive unfolded. The numbering systems used on the boxes containing the glass plates has been consistent since Edward Reeves started in 1855 all the way up until the last glass plate was added in 1974. The remarkably well-preserved archive does not just contain the images, but, as Brigitte describes: "We are working with the ledgers, the account books and the additional correspondence, meaning we can build a complete picture of the local community as well as the history of commercial photography.”

Called 'Stories Seen Through A Glass Plate', this collaborative project presents us with the opportunity to bring these findings into the 21st century and introduce this unique archive to the outside world. With a team of around 30 volunteers, consisting of mostly local residents, the copperplate writing in the ledgers listing the glass plates collection is meticulously transferred into spreadsheets. This will eventually allow for the archive to be searched online by subject.

Furthermore, the digitisation of selected images from the archive has provided the opportunity to recreate and commemorate. Over the years, the archive team have curated a number of events and exhibitions showcasing the collection. In 2017, the Lewes Remembers event commemorated the 237 servicemen and one woman from the town’s War Memorial by representing each name by a person of the same age bearing a flaming torch. It was an opportunity to present new ways to explore the town's history involving younger generations in the community.

PARC's collaboration with the Studio has played a crucial role in allowing the project to reach such depth. For Brigitte, having the opportunity to lead this research project "felt like finding the holy grail." When asked how the project is progressing, she said: "I am totally dedicated to this research, it is such an important work but also very special. I think I may very well still be working on this in 10 years’ time."

- Listen to an interview with Brigitte on the Some Candy Talking podcast

- Find out more about the Edward Reeves Archive Project

- Explore other Knowledge Exchange initiatives happening at UAL

- Would you like to start a collaborative project with UAL? Get in touch with us: business@arts.ac.uk