Beyond the Visual: £250,000 awarded to help change blind people’s experience of art

- Written byAlex Cuncev

- Published date 20 September 2023

A ground-breaking collaboration between UAL, the Henry Moore Institute and Shape Arts which aims to change blind people’s experience of art in museums has been awarded the Arts and Humanities Research Council’s (AHRC) Exhibition Fund of £250,000 and is being led by Dr Ken Wilder, UAL Reader in Spatial Design and Dr Aaron McPeake, artist and Associate Lecturer at Chelsea College of Arts.

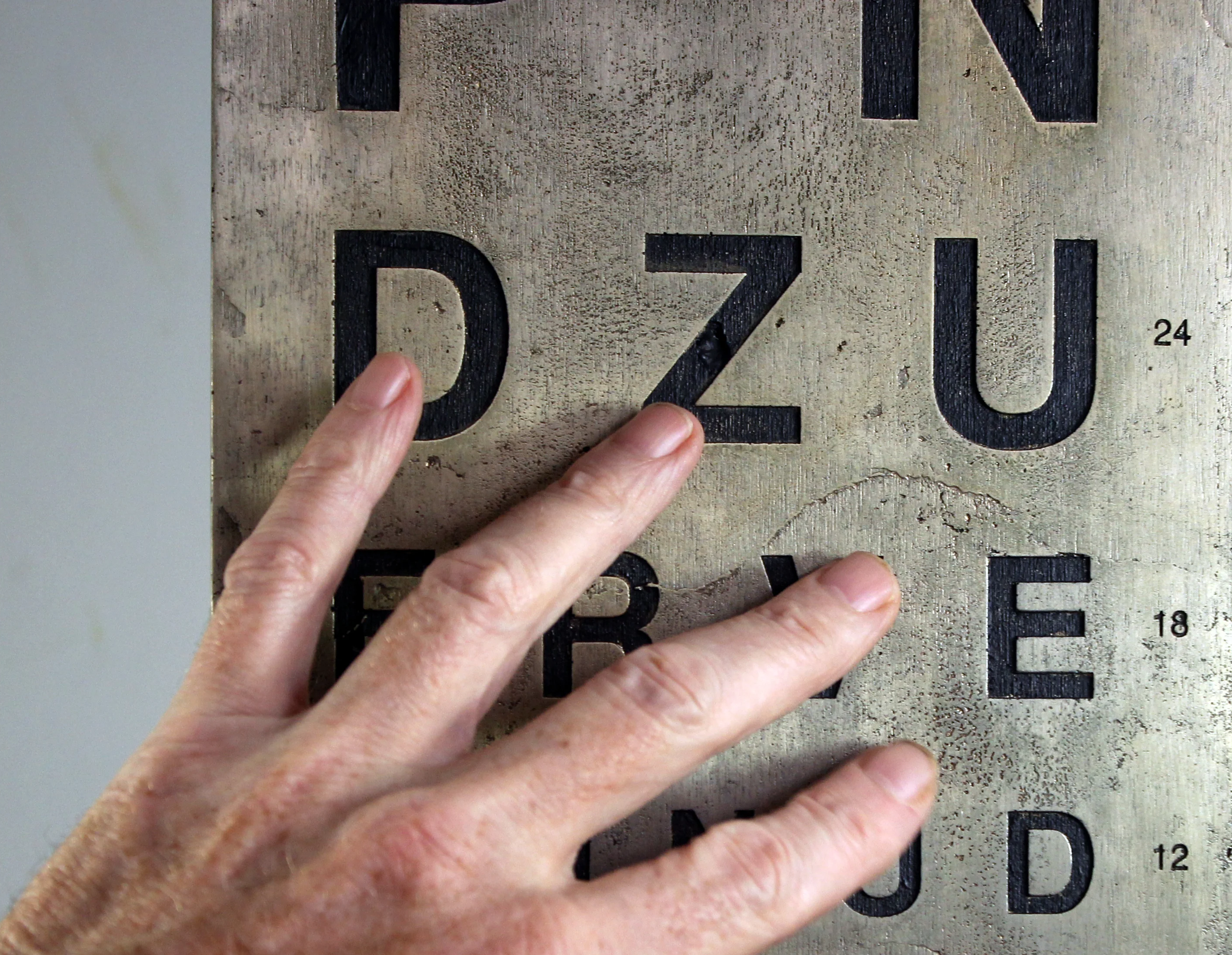

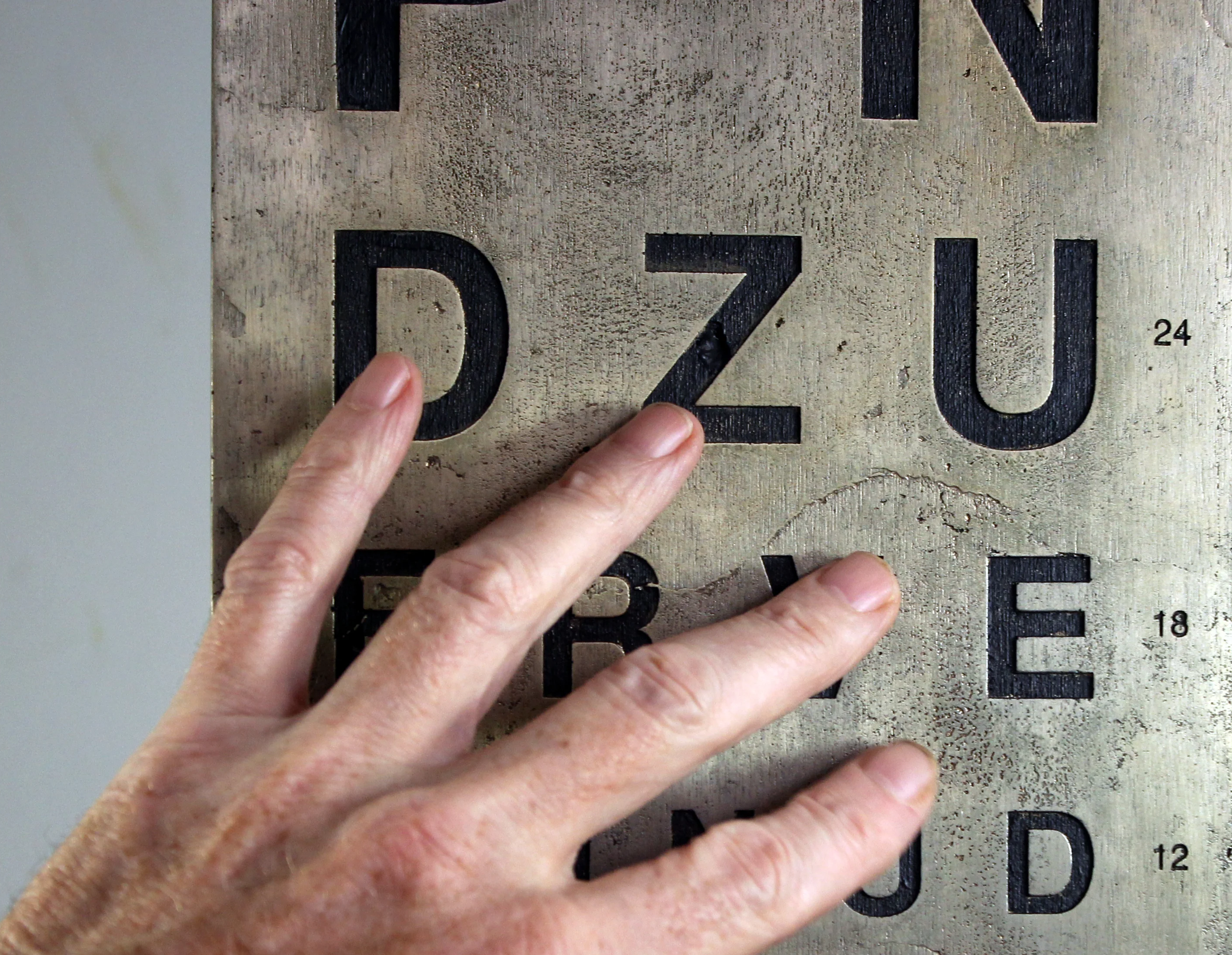

Beyond the Visual will explore engagements with contemporary sculpture using senses other than sight, challenging the dominance of sight in the making and appreciation of art.

The 3-year project will culminate in a free exhibition at the Henry Moore Institute, in November 2025. Integral to the participatory nature of the project are extensive public engagement activities, both before and during the exhibition, including a research season at the Henry Moore Institute running from October 2024 until March 2025. Shape Arts will provide invaluable insights on artist selection and exhibition accessibility.

This landmark exhibition will mark the first major UK-based sculpture showcase predominantly featuring works by blind or partially blind artists within a national institution and is rare in having a blind curator as intrinsic to the project.

To learn more, we caught up with Ken, who is UAL Reader in Spatial Design and Principal Investigator for Beyond the Visual: Blindness and Expanded Sculpture, and his long-term collaborator Dr Aaron McPeake, artist Associate Lecturer at Chelsea College of Arts, and Co-Investigator for the project, who is registered blind.

Hi Ken and Aaron, congratulations on this incredible achievement! Can you tell us more about how the project came about?

Ken: The project emerges out of an interdisciplinary network that was established to investigate how certain new forms of contemporary art – installation, sound, participatory, performance – can open up interesting ways to engage blind and partially blind audiences. The premise is that current access approaches, such as touch tours or tactile maps, are outdated and don’t reflect current art practice. We are interested in considering reflexive practices, where the description of the work is integrated into the piece itself for example, rather than this being something that is done after the event, and how that might open up new ways of engaging an audience, not just blind and partially blind audiences, but all audiences.

You’ve been collaborating for almost 20 years. How has that impacted on this project?

Aaron: We’ve worked together since 2006. Ken and I were on the PhD programme at Chelsea College of Arts. We worked together in that research culture and we’ve also made work together and continue to collaborate.

Ken: The initial idea for this project emerged out of our shared practice, it’s a marrying together of my personal interest in the role of the beholder in appreciating art, and Aaron’s PhD, which discussed the engagement of art by blind and partially blind people. It’s bringing those two factors together and considering what happens when you don’t start from the assumption that everyone appreciating art has full sight.

Who are you working with for this project?

Ken: The partners for the project are Henry Moore Institute, which is the UK’s leading centre for the study of sculpture, disability arts-led organisation Shape Arts, and we are consulting with leading academics and artists concerned with blindness and art including Georgina Kleege, Hannah Thompson, Laurie Britton Newell, who is Senior Curator at Wellcome Collection and David Johnson who is a blind artist, among others. Aaron and I will be guest co-curators for the exhibition, so we have a blind curator in Aaron, which is unusual. We are working with Research Curator Dr Clare O’Dowd at Henry Moore Institute.

Is this exhibition just for blind and partially blind people?

Ken: While blind and partially blind people are identified as a primary audience, the exhibition is not intended to be for the blind, but rather sets out to not exclude an audience who are often marginalised by exhibitions where beholders are unable to touch or interact with the works. This is consistent with Hannah Thompson’s term ‘blindness gain’, where non-blind audiences benefit from the knowledge gained from the experience of blind audiences, challenging the frontality of vision in favour of a 360-degree engagement.

Aaron: It’s about how ‘blindness gain’ can actually enhance the experiences of others by using those modes and practices.

What are some of your ambitions for the project?

Ken: There is an underrepresentation of blind and partially blind artists in archives and one of the goals of the project is to construct a database of artists who are blind or partially blind and working in a sculptural medium, which could then be accessed by other curators and artists as a resource.

Aaron: We want to create a case study for other museums and galleries and have a general cultural effect on the museums and galleries universe. I work as a consultant on access issues in the museum sector and what we find is that the knowledge sits with specific individuals who might then move on to another role. Through this project we want to make a mark, so knowledge doesn’t just sit with a person but it actually becomes integral to the institution. We hope its impact will be international, not just in the UK.

What will the experience be like for visitors to the exhibition?

Ken: All the artworks will be able to be interacted with in some way and the majority of work will be by blind and partially blind artists.

We will also think very hard about navigational systems. The audio description will include the input of the artist and this will inform the decision about what artworks to include. We want to consider the navigational systems as integral to the exhibition itself so it may be that this is commissioned as an artwork in its own right.

What about after the project – what will its legacy be?

Ken: The exhibition will be an exemplar, we hope, of accessibility. The hope is that it enacts institutional policy change not just for the Henry Moore Institute but for other institutions around the world.

We also want to shift the debate about what art practice is. If you start to think about artwork from a broader perceptual base, if you think about people that have broader perceptions, whether they are blind, deaf, have other disabilities or neurodiversities, and you start to think about them as your audience, then you arrive at a much broader understanding of what art practice is. That has the potential to enhance the experience for everyone.