Sophie Jump is an Associate Lecturer and Researcher at University of the Arts London, teaching on BA and MA Performance Design and Practice at Central Saint Martins, and BA Theatre Design at Wimbledon College of Arts. She's also a visiting lecturer for MA Scenography at Central School of Speech and Drama.

Sophie designs for theatre and performance and won the overall Gold Medal at World Stage Design 2013. She is also Co-Artistic Director and designer for performance company Seven Sisters Group whose site-specific work has been seen at many of the UK’s leading venues and companies (Royal Opera House, Royal Festival Hall, Royal National Theatre, English National Ballet) as well as internationally (Trainstation (1998-2004) UK and international tour, Boxed (2006 and 2012) Auckland, NZ, The Tempest (1997) Shared Experience UK and international tour).

Her designs were selected to represent Britain at every Prague Quadrennial exhibition of world theatre design between 1999 and 2011 and have been exhibited at the V&A museum several times.

Her PhD is on the theatre designers Jocelyn Herbert and Motley and her post-doctoral research is now focused on the Jocelyn Herbert Archive, a joint collaboration between Wimbledon College of Arts and the National Theatre.

The Role of the Theatre Designer is just one output of that collaboration, and here Sophie tells us more about this project and how it came about.

How did this project come about with the National Theatre?

When applying for the Fellowship we were asked to propose an outcome, and I had the idea of making a website that explains what it is that performance/theatre designers do and why theatre design is important. It has been a constant surprise to me that many people still think of theatre design as decorative and don’t understand the crucial contribution it makes to productions. There is also a relative lack of resources about the processes and methodologies of theatre designers which I wanted to address.

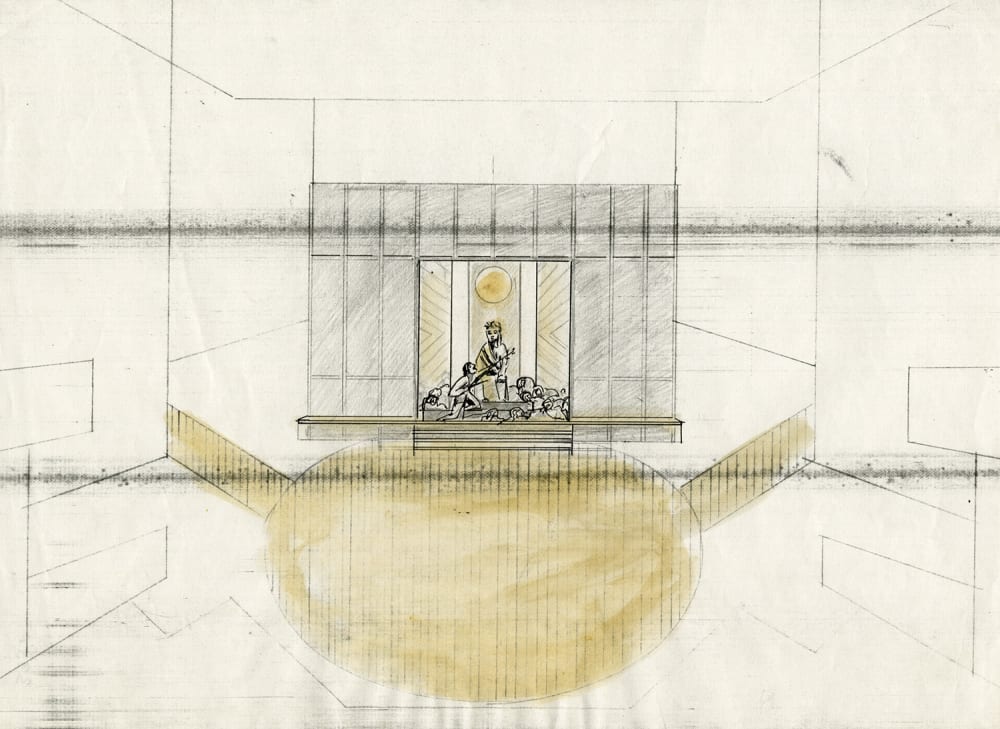

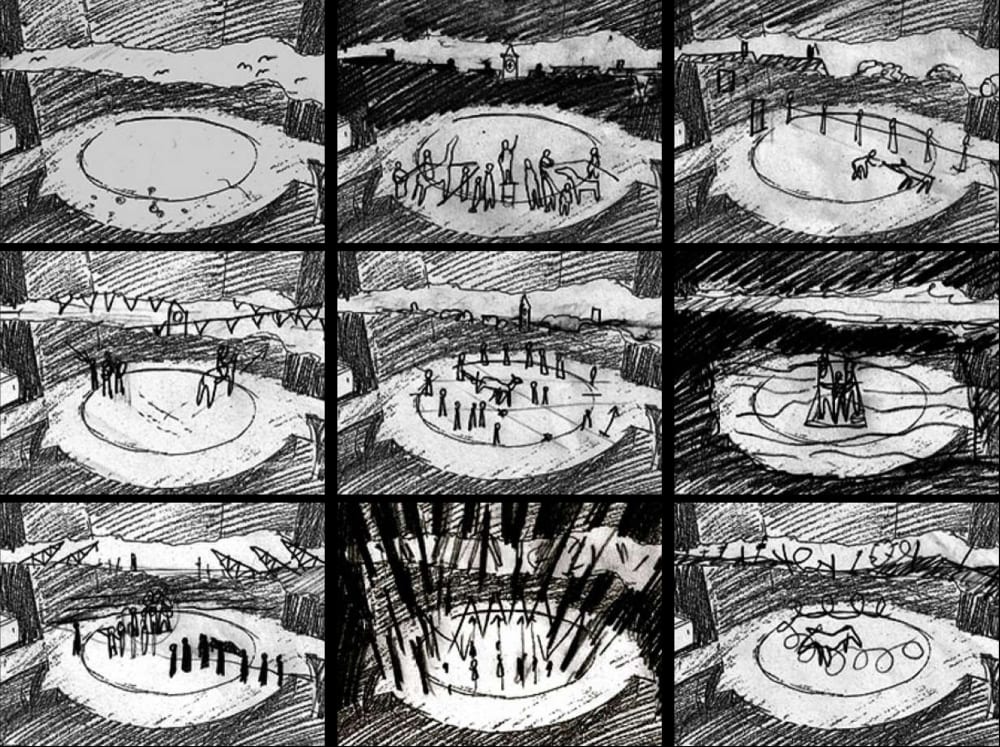

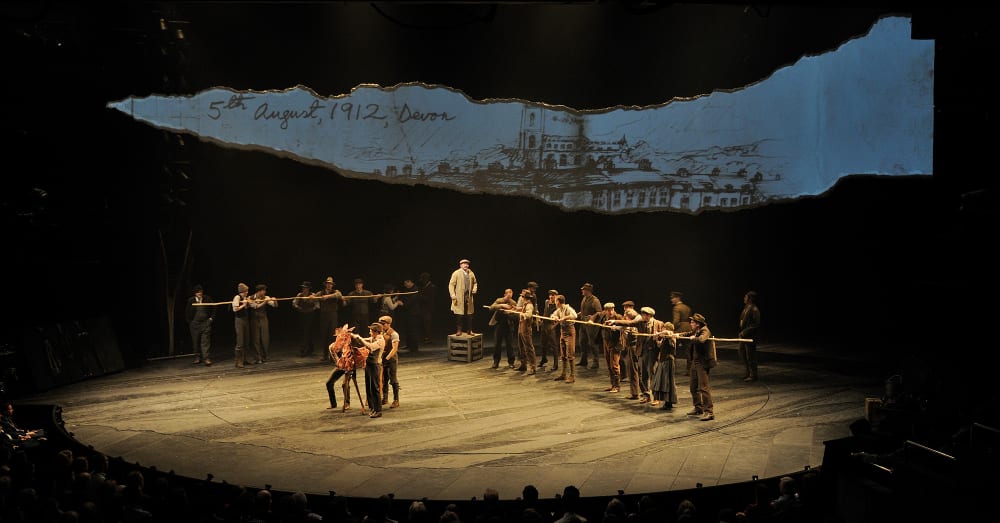

I decided to create a website using 3 iconic National Theatre productions as case studies to explore how designers work and what impact their designs have on the audience’s experience and interpretation of the play. The productions are; The Oresteia (1981) designed by Jocelyn Herbert, The Mysteries (1977-1999) designed by William Dudley, and War Horse (2007 to present) designed by Rae Smith. The website is mainly aimed at theatre design students but is also designed to be accessible for the general public and those with an interest in backstage arts.

, Wimbledon College of Arts, UAL

But who was Jocelyn Herbert and why is she such a significant figure in stage design?

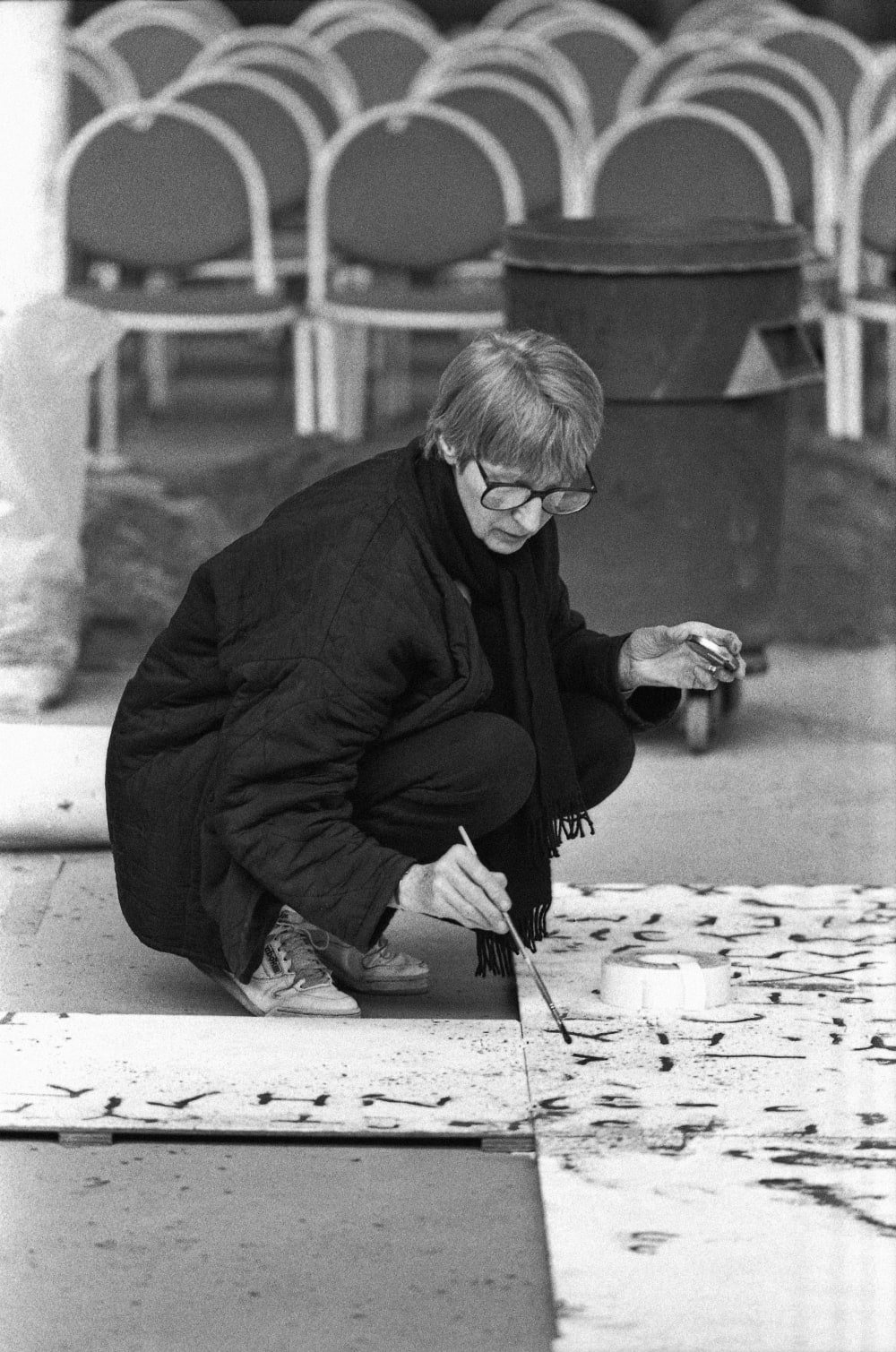

Jocelyn Herbert (1918-2003) studied at the London Theatre Studio under Michel Saint Denis and the theatre design group Motley between 1936-1938. When the English Stage Company at the Royal Court Theatre was founded in 1956 she was employed as scene painter for the company and went on to be, in effect, a resident designer there.

She was notable for developing close and long-standing collaborations with writers and directors such as John Dexter, Lindsay Anderson, Peter Hall, Arnold Wesker, Samuel Beckett and Tony Harrison. They valued her ability to create a visual language that complemented and supported the dramatic text and intentions of a production but also came to rely on her dramaturgical judgement. As such, she became an inspirational role model to the theatre designers that came after her.

She designed the premieres of many plays that would become 20 century classics and became known for a pared back minimal aesthetic. Herbert’s attitude to design might best be summed up by her as follows:

‘For me, there seems no right way to design a play, only perhaps a right approach – one of respecting the text, past or present, and not using it as a peg to advertise your skills, whatever they may be, nor to work out your psychological hang-ups with some fashionable gimmick.’

She left behind an extensive archive which is now housed at the National Theatre Archive. It is remarkable for its breadth, containing not only drawings for most of the productions she designed but letters, notebooks and sketchbooks, masks, photographs and models.

So in today’s terms, post Jocelyn Herbert, how do you define the role of the theatre designer?

At its most basic level the person who decides what the performers will wear, what kind of aural, visual or spatial environment they will inhabit, on the objects or props with which they engage, is usually called a theatre designer.

However, words are important and our choice of them often reflects what we think about what they are describing. For example, for much of the early to mid-20 century ‘décor’ was a common term for what designers created on stage, and ‘décor by’ was interchangeable with ‘designed by’ in theatre programmes. To a modern-day theatre designer ‘décor’ implies a superficiality that does not align with how they see their role. Some might even feel that ‘theatre designer’ does not adequately express their job, and they may prefer ‘scenographer’ or ‘performance designer’.

The changing use of words and names is one demonstration that the status of the designer has changed throughout the 20 and early 21 centuries. Many designers now consider themselves to be collaborators together with the director, performers and others involved in creating the production. Alongside this development, the position of the dramatic text as central to the creation of performance has been challenged and there are companies and artists for whom design elements are equal in importance to the spoken word, or even in some cases supersede it.

The dramatic text, however, is still dominant in the majority of UK theatre making and in these cases the theatre designer will analyse and interpret that text. Additionally, the designer’s process includes thinking about the practicalities of a production, such as the budget, the location, the target audience, the resources available, and who else they are working with. Moreover, they have to incorporate any themes that they and the director have chosen to highlight.

The designer will consider these factors, and more, to create a visual, spatial or aural interpretation for the production via their designs, which may include the sets, costumes and props. They then have to oversee the transformation of their ideas from the drawings, diagrams or scale models to an actual material staging.

, Wimbledon College of Arts, UAL

Is that why you chose War Horse as one of the case studies for the resource?

I chose all the case studies because for each of them it was clear that the designer had been influential in working out how to stage the work.

For War Horse Rae Smith created an open and generous space for the actors, puppets, lighting and projection to work together seamlessly to tell the story in a simple and honest way. The projection of her sketches onto a torn strip of screen arcing around the stage lifted the portrayal of the locations into areas of imagination and feeling which helped the audience to connect to the story.

During the creation of The Oresteia Jocelyn Herbert worked closely with director Peter Hall and the performers to develop the masks. Not only was Herbert contributing to the process by working out the best kind of mask to be used, but she gave input into the way that they were used.

William Dudley’s spatial arrangement of the Cottesloe theatre for The Mysteries, encouraged the audience to become receptive to the themes of the plays as people’s theatre. The theatre was covered in the ordinary objects of working people, and the actors mingled with the standing audience which promoted a sense of a shared experience.

, Wimbledon College of Arts, UAL

You said that intention with the website was to raise awareness of the role of the designer. Do you think Jocelyn would be proud, and from all accounts it seems there was a real humility to her, to see her influence and legacy extended through this work?

Jocelyn stipulated that she wanted her archive to be as accessible as possible and for students and researchers to use it. This is why her archive was first housed at Wimbledon College of Arts and is now at the National Theatre Archive. I think she would be pleased that the website makes it possible for people around the world to access some examples of her work and her design processes. My hope is that website visitors will be encouraged to come in person to explore the archive, and to find out more about theatre designers, what they do and why it is important.

To explore The Role of the Designer, visit the National Theatre’s micro-site on Google’s arts and culture.

Find out about theatre related courses at Wimbledon.