MA Conservation students at Camberwell had the opportunity to indulge in the fascinating world of medieval pigments through a series of workshops that included lectures in the morning and practical sessions in the afternoon. Second year Conservation students learnt about pigments and dyes used to paint Medieval manuscripts in European, Middle Eastern, and Asian traditions.

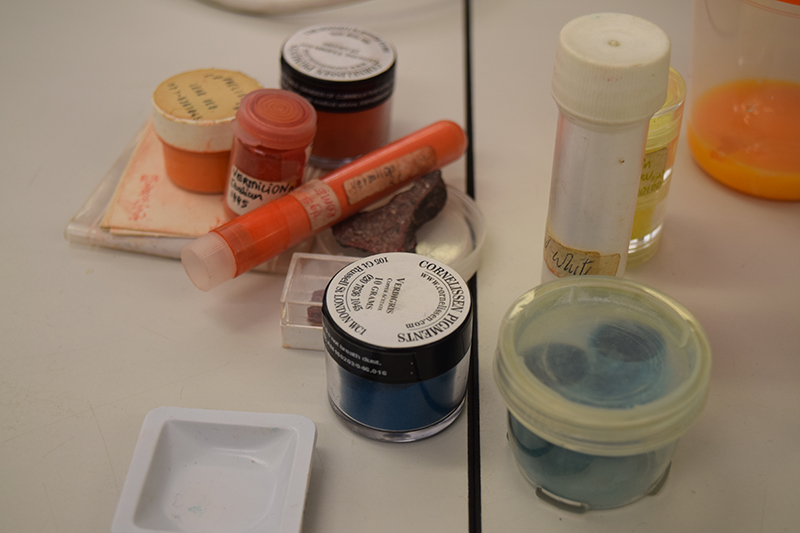

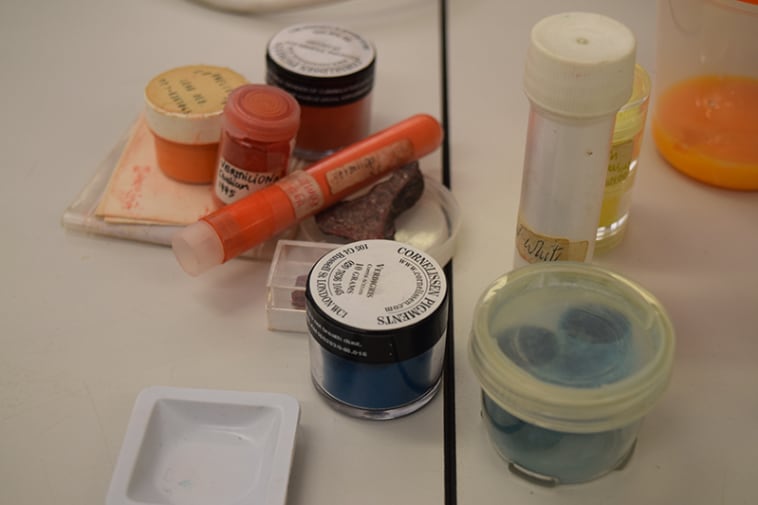

The workshops ran across three days and started with minerals pigments. Day two explored pigments originating from plants and animals and on the final day they studied pigments made of metal. Students experimented mixing, grinding and painting with the dyes, the practical sessions taught them how to prepare pigments and make paints using different traditional recipes. The workshop was taught by subject specialist Cheryl Porter who guided students to recreate the colours used by artists throughout the medieval era. Cheryl is a Camberwell alumna, Director of Montefiasco Project, Deputy Director of Thesaurus Islamicus Foundation & Dar al-Kutub Manuscript Project, and freelance conservator.

When arriving to the conservation lab on day one of the workshops we found Cheryl pouring vinegar into a small plastic bowl which contained a small piece of copper hanging from a string. As she sealed the bowl, Cheryl told us that a chemical reaction will begin the process of pigment production and that in about 24 hours we should see the colour coming through. We were immediately captured by this magical process and set up to ask students about their own experience. Below, two MA Conservation students tell us about their experience each day working with the pigments and Cheryl.

Day one: Jessica Phipps Wardle

“On the 31st January Cheryl Porter came to the MA Conservation studio to give a three day workshop on pigments used in the Medieval era. We looked at the historic background to the pigments from their trade and production, to the application and also their physical and chemical properties. For each group of colours we also made samples and tried them with different binders such as gum arabic, egg yolk and egg white.

The first day was spent looking at the earth, natural mineral and synthetic colours. Earth colours are some of the oldest pigments used, they are easy to prepare, widely available and so cheap to use. They are also chemically inert so will not react with other pigments or substrates. We mixed up yellow and red ochres and green earth pigments. The natural mineral do not require chemistry to get the colour but a longer processing and rarity of some of the minerals makes them more expensive and desirable. Ones we looked at and made included Lapis Lazuli and Azurite, Malachite and Orpiment. Finally the synthetics were categorised together as they required chemistry to get the colourant. Lead white, lead tin yellow and lead red as well as verdigris and vermillion were discussed and samples made to see the difference in intensity compared with the other pigments but also how easy they were to work with; if they went into the suspension well and how they applied in different binders.”

Day two: Mathilde Renauld

“On the second day, Cheryl introduced us to more natural colours, mainly blues and yellows, as well as the metals that Medieval artists would have used in their illuminations. Metals such as silver and gold were used in leaf form, or could be ground and mixed with a binder to form a paint, such as shell gold. These variations have different uses and potentials: leaf gold could be used as a block colour, applied onto a gesso ground, then burnished, which gave it a smooth, raised surface to catch and reflect light. Otherwise, shell gold could be used for writing in gold, or for highlights in painted designs. The blue pigments discussed were ultramarine, indigo, and woad. The latter two come from plant origins, whereas ultramarine (beyond the sea) is a mineral pigment originating from the stone lapis lazuli, traded in from Afghanistan.

Choice of colour was discussed, with regards to iconography and representation. For example, it was explained that the colour of the Virgin Mary is traditionally blue since the 12th century, as it was the colour associated with mourning. Not only did we discuss the origin of such colours, also that of metals, since availability and trade routes dictated whether artists in certain regions could or couldn’t access certain colours and metals. For example, gold leaf began being used when gold coins started being traded into Europe from Arabic countries. Indigo similarly, was imported from East Asia from the beginning of the 1500s, the East India Company would even force its use later on so as to bolster its business.

Our afternoon session allowed us to mix blue pigments with binders such as gum arabic and egg white, and mix it with other colours such as lead white. We also got to practice some leaf laying with gold and silver.”

Day Three: Jessica and Mathilde

“On the third day of the workshop, Cheryl Porter took us through organic pigments, their use, and their production. Organic colours tend to fade rapidly, so the best place to see evidence of their use is in manuscripts, where they have been kept away from light inside the book. In the workshop, Cheryl made up samples of each organic pigment and demonstrated how they would have been stored and used. Organic colours could be used either from clothlet format or lakes, the difference being that a lake is an organic colour precipitate onto alum, which renders it insoluble. Clothlets on the other hand are carriers or soluble colours, which need a mordant to be used.

The colours we focused on were: yellows (Weld, Buckthorn, and Saffron) and reds (Madder, Brazilwood, Lac and Cochineal). Organic pigments were also used in mixtures to obtain greens and purples. Weld, Buckthorn, Saffron, Madder and Brazilwood are all plant-based colours, available with little processing, and as such are some of the oldest colours used. Lac and Cochineal are colours obtained from insects, the latter of which is an endangered species so we sampled a historically-made pigment instead of making our own on the day.

This three-day workshop has enlightened us and has brought to our attention many aspects of historical colour-science and their identification and degradation. We are grateful for the time and enthusiasm which Cheryl gave us!”

Related links: