This week saw the opening of the latest exhibition at Chelsea Space. Mario Dubsky: Xeno Factor includes paintings and drawings by the influential artist and educator Mario Dubsky (1939-1985). Including material from all the phases of his working life, the show explores his quest for a powerful visual language with which to express his ideas as a gay man and artist.

Mario Dubsky was born in 1939 and died in 1985 of AIDS. As an educator, he taught at the Royal College of Art, the Slade and, in the 1970s and 1980s, Camberwell College of Arts.

The exhibition is co-curated by Chelsea Space’s Director Donald Smith, who also teaches on MA Curating and Collections at Chelsea College of Arts and has worked at the college for 26 years. But before his days at Chelsea, he was himself a student of Dubsky’s when he studied at Camberwell from 1981-4. We spoke to him about what visitors can expect to see in the show, and how the works on display relate to the evolution of the artist’s practice and personal life.

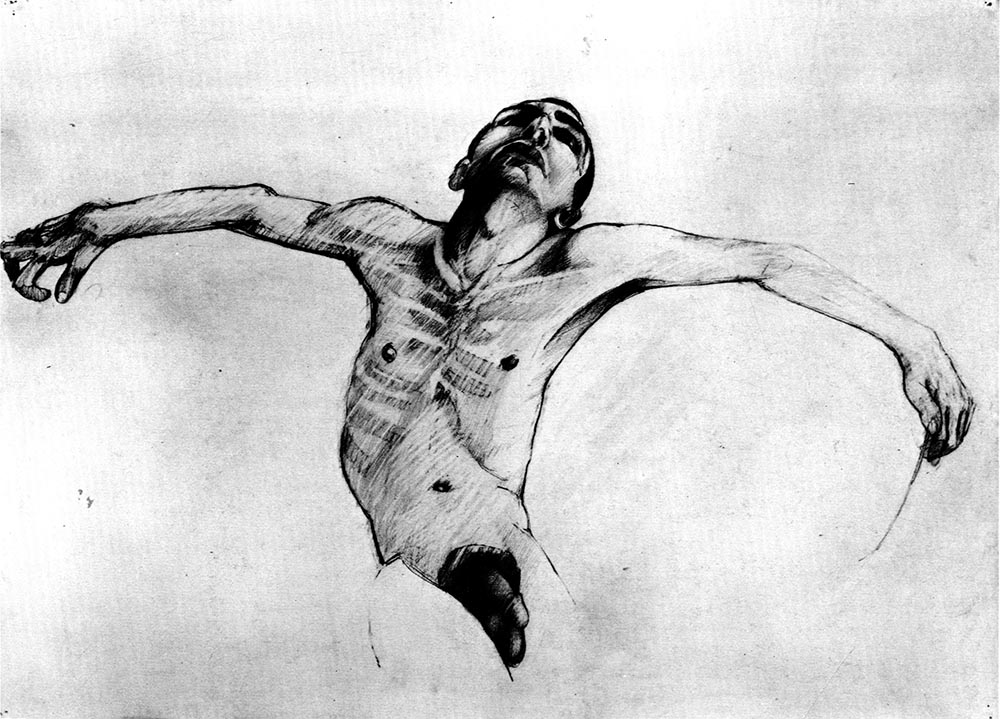

The exhibition opens with a series of life drawings Dubsky made in the life room at Camberwell between roughly 1975 and 1983, spanning eight years. “The students would benefit from teaching through example,” explains Donald “so we’d all be drawing the same model as the teacher, from different angles.” These works show a range of his drawing as it developed along with his intellectual and political interests. Beyond them, at the top of the ramp which leads into the main gallery space, an etching and a painting from the 1950s will be on display. “These were made when Mario was a very precocious young student at the Slade – he was about 16 years old when he started there”.

Dubsky was born in the UK to parents who had recently arrived as refugees from Vienna before the outbreak of the Second World War. “He was baptised and his parents were baptised” Donald explains, “but they had Jewish ancestors. There was always a cultural confusion present in Mario’s early life: even his name, Mario is very Mediterranean-sounding and then it is followed by Dubsky, which is from the Slavic, Jewish side of his heritage. But he very much embraced his complex cultural past.” This is clear from his early work, which was heavily influenced by major events such as Hiroshima, Guernica, the Holocaust, the pogroms and anti-Jewish issues that Europe faced during his childhood. “These events were close to his own birth. When he arrived at the Slade as a young student, he made work which was abstracted from the figure but very heavily wrought.”

After his time at art school, Dubsky travelled in Europe where he not only started to develop his understanding of the classical and western art tradition in Rome, but also, for the first time, started to understand his own sexuality when he visited cities like Berlin and Amsterdam. Donald believes this was an important time for him, “because once he understood that he was homosexual and that it was possible to celebrate and to be ‘out’, he didn’t ever try to deny that. He tried to work out how he was going to build that into his own practice.” His travels took him not just to Europe, but through Serbia and Macedonia and to Mount Athos, Cappadocia, Antioch, Aleppo and Damascus. It was here that he developed his interest in the history of Arabic culture in Europe and beyond, and his work from this period onwards shows the ways in which he began to marry all of this into his own personal mythology. “Historical, classical, mythological and archeological influences – he tried to bring them all together and make work that reflected his own life in relation to this wider history.”

But this approach put him at odds with the pop and abstract work that was being made in the UK by other artists at the time. He had his first solo show at the Grosvenor Gallery in 1969 but the work wasn’t yet fully formed. Reflecting on what was shown at this time, Donald believes “ he was obviously trying to somehow please the professional art world and be part of that, but it was sort of at odds with where he was and where he wanted to be.” Later that year, Dubsky visited the US where the Stonewall riots (an uprising by the homosexual community against homophobic police abuse), the civil rights movement and anti-Vietnam protests all informed his political and moral ideas.

This set him apart from the approaches of some of the other openly gay artists that were his contemporaries. “David Hockney’s work, for example, was very much connected to illustration and leisure, the idea of the ‘gay at play’, whereas Andy Warhol’s output was much more camp. Mario felt like he wanted to be more political, more issue-driven and somehow more personal in what he was doing.” It was here that the figure really started to come through as a central motif in his work, as Dubsky began to ask himself: what do you do with the life room model? How do you raise your drawing above being just a purely anatomical study? “This for me is where he work becomes really interesting” Donald continues, “because he imbues the human figure with all of his sexuality, with all of his seriousness and his political drive. The work contains his morality, his desire to be himself and for his own life to be a subject for art. I think it’s here that his drawing becomes extraordinary because he is trying to embody all that in the simple human figure.”

It was after his trip to the US that Dubsky started teaching at Camberwell. When Donald joined in the early 1980s, he met a very serious, intellectually rigorous man who was quite a tough teacher. “He was a bit scary!” he admits. “Teaching was very different in those days. He was quite aggressive by nature and could be very provocative. He said some very direct things to me but, on reflection, they actually always contained an absolute gem, a nugget of truth that gave me a way to progress and improve the work I was making or improve my thinking. I found the feedback extraordinarily rewarding, even though sometimes the delivery left a lot to be desired. If you persevered with it there were so many valuable lessons to learn. There are comments that even today I might say to a student that were things Mario once said to me. So overall it was a very rich experience.”

Camberwell during this period was “an amazing place to be”, recalls Donald. “There were three evening life classes a week, each run by different tutors with something quite different to say. In turn, each of those teachers had certain students that adopted their language or ideology and it was an incredibly vital time for drawing, something for which it quickly became renowned.”

Being one of Dubsky’s students also gave Donald a natural introduction to other artists from an earlier generation who had studied under him, and it was one of these, David Ferry, who became a friend, colleague and co-curates this exhibition. “David had been a student at Camberwell in the 1970s and was invited back by Mario to do some teaching – I was one of his guinea pig students. Because we had both been taught by Mario we found we had a lot of common ground and were engaged in the same kind of visual language. We were coming from a similar position and we quickly bonded.”

When Donald was in the third year of his degree, David asked him to be part of an exhibition with three other artists: himself, Steve Smith, and Rita Smith, who had all been taught by Mario at Camberwell in the 1970s. “David wanted me to be the fourth artist in this show which was to be held at the Grundy Gallery in Blackpool. It had a fantastic reputation and you can imagine that it was incredibly significant for me when David asked me to take part: it was 1984, I had been an art student, first at Portsmouth and then at Camberwell for just three years. The exhibition was planned for 1987 – that was as long as my BA course had lasted! At that time, I had no idea if I was going to still be an artist in three years time, so it was an amazing affirmation of my work to be asked. Our work was all quite different, but there was a kind of root for all of us in Mario’s teaching and his work. It was a brilliant opportunity, and really kickstarted my practice for me.”

Sadly, Dubsky would not live to see the exhibition of his students’ work. He died in 1985, less than a year after a major show of his own work, the title of which has inspired the name of the Chelsea Space show.

The exhibition took place in 1984 at the South London Gallery (SLG), then called the South London Art Gallery, which is next door to Camberwell College of Arts. It was called X Factor, a reference to the Greek form xeno, meaning ‘stranger’ or ‘unknown quantity’. “Yes, it did have a certain connotation with ‘xenophobia’ and fear of the other” Donald remembers. “This was something that interested him because his parents were refugees and because his sexuality made him feel like an outsider in so many ways. But as well as that there was a reading of it that also referred to the other as in ‘the unexplained’ – he was interested in a more complex reading of it as a term.” It is with this in mind that Donald decided to name this show Xeno Factor, an homage to that exhibition and to perhaps more fully explicate some of Dubsky’s thinking around that word.

The show at SLG included some work that will shown at Chelsea Space, including a large piece titled Natural History Remains which was made between 1975-77. This triptych will take up almost all of the longest gallery wall at Chelsea, and reflects Dubsky’s preoccupation of extremes coming together, marrying the mythological aspects of Greek and Roman culture with a more primeval, primordial history of man.

Donald remembers the private view of X Factor very clearly. “In the build up to the show Mario was really tense and quite hard to deal with: he had become angry and withdrawn, and generally ill at ease” he recalls. “He worked tirelessly and meticulously to create the installation that he wanted. On the day of the exhibition Mario stayed in the gallery pottering and brooding. By the time the exhibition opened, it seemed as if a cloud had descended on him and people didn’t even seem to feel like they could approach him to congratulate him.” Dubsky died of AIDS less than a year later. Donald isn’t sure if he knew at the time that he was ill. “It was possible that he had an idea that this show was his opportunity to wrap things up, and really take a more retrospective look at his work. In the catalogue for that exhibition he tells his life story and the show was very well-rounded. It wasn’t just a slice of time, it was a final, considered overview of his practice.”

However, Donald is glad to recall that the evening didn’t end as soberly as it began. “Later that night, Derek Jarman turned up with Andrew Logan and a bunch of the ‘out’ gay art community and suddenly the whole event changed. It went from this very somber serious, quiet event into a kind of festival. It was very striking to see and I was pleased for Mario as it really lightened his mood. He was finally able to celebrate his work, as he deserved to do.”

Mario Dubsky: Xeno Factor runs from 27 September to 27 October at Chelsea Space.

Find out more about studying MA Curating and Collections on our course page.

Image at top of page: Mario Dubsky, Posture V