Opening this week at Chelsea Space, The Sun Went In, The Fire Went Out: Landscapes in Film, Performance and Text, is an exhibition exploring ideas of land, site, duration and re-presentation, and comprising works by three artists – Annabel Nicolson, Carlyle Reedy and Marie Yates – who were vital in the development of key movements within the avant-garde in London from the 1960/70s.

Through film, performance and text, this exhibition will privilege ephemeral practices, displaying art works that are iterative, morphic and responsive, re-framing the strategies of documentation and its use within exhibition making.

We spoke to curator Karen Di Franco about the themes and concerns which have brought these artists’ works together for the exhibition and how she and her co-curator Elisa Kay have been inspired and informed by the work of archeologist and writer Jacquetta Hawkes.

Marie Yates, Field Working Paper 9, from the series, The Field Working Papers (1971-73). Image courtesy of Marie Yates.

“I have been working with my friend and fellow curator Elisa Kay for about two years on this show” she begins. “It has come from various areas of interest and research but definitely from our collective interest in Jacquetta Hawkes’s work. She has recently become better known as she wrote the screen play to Figures in a Landscape, the film about Barbara Hepworth that was featured in the retrospective of her work at Tate Britain. But beyond this, she is a really interesting woman: she was

one of the founding members of CND and an activist in the anti-nuclear campaigns of the 1980s. She was a celebrated archeologist and writer and she curated the ‘The People of Britain’ display at the Festival of Britain on the Southbank in 1951. She was a member of UNESCO and was a prominent public figure but her legacy is quite obscure now. We’ve always wanted to do an exhibition or something about her – but it hasn’t quite worked out like that. Instead, she has become the framework for thinking about other artists that we’re working with.”

The exhibition will include a selection from Marie Yates’ series, The Field Working Papers (1971-73), a conceptual gallery project made for The Midland Group Gallery in 1973 that features extensive documentation in image and text of the landscapes of the West Country, as well as environmental sculptural forms and improvisation sound performances;

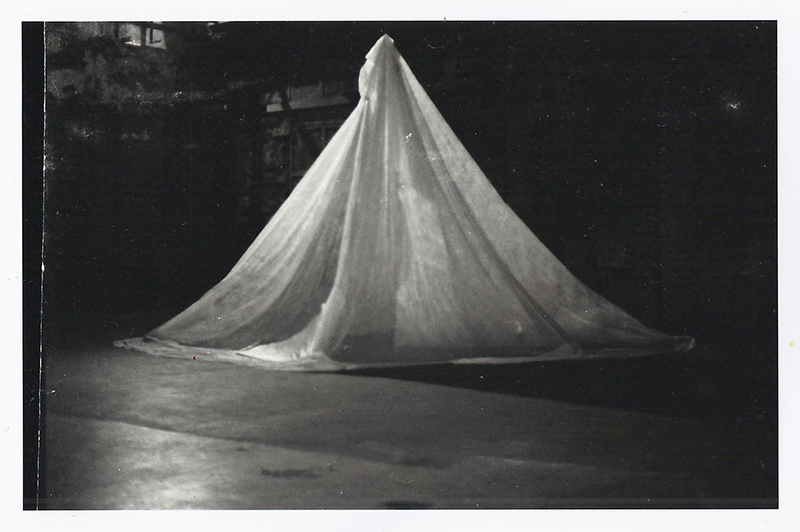

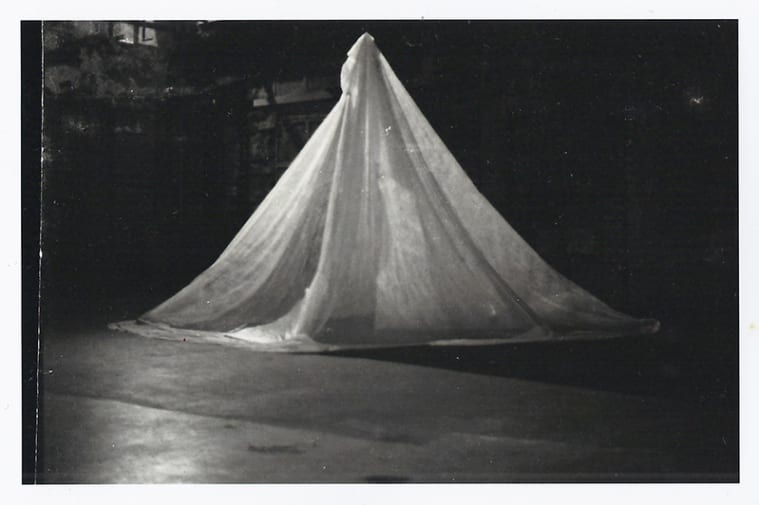

work by Annabel Nicolson including documentation of performances in the landscape and other material from her artist’s book Escaping Notice (1977), and archival material from exhibitions such as Concerning Ourselves (1981) and Of the Cloth (1988). A new performance installation by Carlyle Reedy will integrate and rework material and documentation from earlier performances including Living Human Sculpture in Contemplative Time (performed at the Royal Court, 1972) and A Good Wind (Riverside Studios, 1977).

Marie Yates, Field Working Paper 11, from the series, The Field Working Papers (1971-73). Image courtesy of Marie Yates

An accompanying film programme curated by Lucy Reynolds, a publication and an online resource will compliment the gallery display with archive and collection materials as well as interviews with the artists and contributions from other practitioners.

Each of these artists have elements of their work that inform and connect to each other. Themes including duration and space, a relationship to landscape, and their connection to feminist ideas and groups, that likewise, provide an approach from all three to understanding landscape through a long history of human activity also connects them back to Jacquetta Hawkes.

This is not the first time Karen or Elisa have worked with some of the artists in the exhibition. “This show continues connections we have both made with artists at various times, I worked with Carlyle Reedy for the show Icons of a Process at Flat Time House in 2014. I’m really intrigued by her practice and saw a performance of hers recently – she doesn’t perform very regularly – which was incredible. She’s also a published poet with decades of experience in public readings and performances.and she knows instinctively how to hold an audience. With this in mind I’ve wanted to do something performative with her.”

Carlyle Reedy, Slide documentation of Living Human Sculpture in Contemplative Time (performed at the Royal Court, 1972). Image courtesy of Carlyle Reedy

“Since working on the Icons show, we have continued a conversation about her work and I’m interested in how Carlyle is continuously working on things and so there’s never really a beginning or an end to a lot of her work.” This doesn’t make it easy for Karen as a curator though, she explains. “Work of this nature brings a variety of complications in terms of collecting it, even naming it or attributing a date to it, before you’ve even thought about displaying it.”

While the artists in the exhibition are not as well known or as widely collected as some of their male counterparts might be today, Karen gives little credence to the notion that they are in anyway ‘forgotten’. “I’m not particularly interested in the idea of discovery or rediscovery” she explains. “I think it’s easy to classify people as being ‘forgotten’ and I don’t want to do a disservice to the women in this show by not acknowledging the breadth and history of their practices. I think they have their own profiles in specific areas and yes, there is an issue of visibility in terms of the mainstream, perhaps, but I think that is about the narrowness in scope of art historical narratives, where multi or trans-disciplinary artists are not accommodated because their work is difficult to pin down, rather than what is of interest to artists, gallery visitors or students. In curating the show we have been mindful of that, but the key, for me, is for there to be a dialogue about the works between the artist, the curators and the audience in and out of the gallery, and if we can achieve that, I think we’re on the right track.”

The Sun Went In, The Fire Went Out: Landscapes in Film, Performance and Text takes place at Chelsea Space from 27 January – 4 March 2016 with the private view taking place on Tuesday 26 January, 6-8.30pm.

For more information about the publication, online resources and associated events in London and Bristol, please check arts.ac.uk/chelsea/events