Philippa Kate Weaver, studying MFA Fine Art at Wimbledon College of Arts, compares the lives and work of artists' Dorothea Tanning and Louise Bourgeois.

Does sanity rely on creativity, or does creativity rely on “madness”?

The Tate Modern’s critically acclaimed Dorothea Tanning exhibition surveys the seventy-year career of this American artist whose work “always asks us to look beyond the obvious”. The exhibition runs until 9th June.

It is gratifying that the Tate Modern has dedicated such space to a woman artist. The journey of Dorothea Tanning’s life is fascinating, the breadth of her work is vast. She deserves this attention.

The exhibition runs alongside the Tate Britain’s rehang “60 years” which continues the Walk through British Art with work by women artists from 1960s to the present day. As Adrian Searle comments, one is struck by how limited the Tate’s collection of women artists is. However, the effort is to be commended.

The Tate, who over the last 20 years, has cultivated our appreciation of Louise Bourgeois, might have done well to compare her with Tanning. Such an exhibition would have been rather more sensible than the RA’s recent abortive attempt to compare Bill Viola with Michelangelo.

Tanning vs. Bourgeois

Although there are obvious differences between them, the similarities between the two women are striking and sometimes weirdly uncanny.

Both lived very long lives. Dorothea Tanning (1910–2012) died at her home in New York City on January 31, 2012. She was 101 years old, and had just published her second collection of poems. Bourgeois (1911 – 2010) died of heart failure on 31 May 2010, at the Beth Israel Medical Centre in Manhattan. She had continued to create artwork until her death, her last pieces being finished the week before. She was 98. Tanning was American but she lived in France for 20 years. Bourgeois was French but she lived in America for 70 years (1938 – 2010).

Tanning's husband, Max Ernst, died in 1976. They were married for 30 years. Bourgeois' husband, Robert Goldwater, died in 1973. They were married for 36 years. Both created a strong friendship with, and were influenced by, a male mentor / assistant in later life. Tanning with poet, James Merrill and Bourgeois with artist, Jerry Gorovoy.

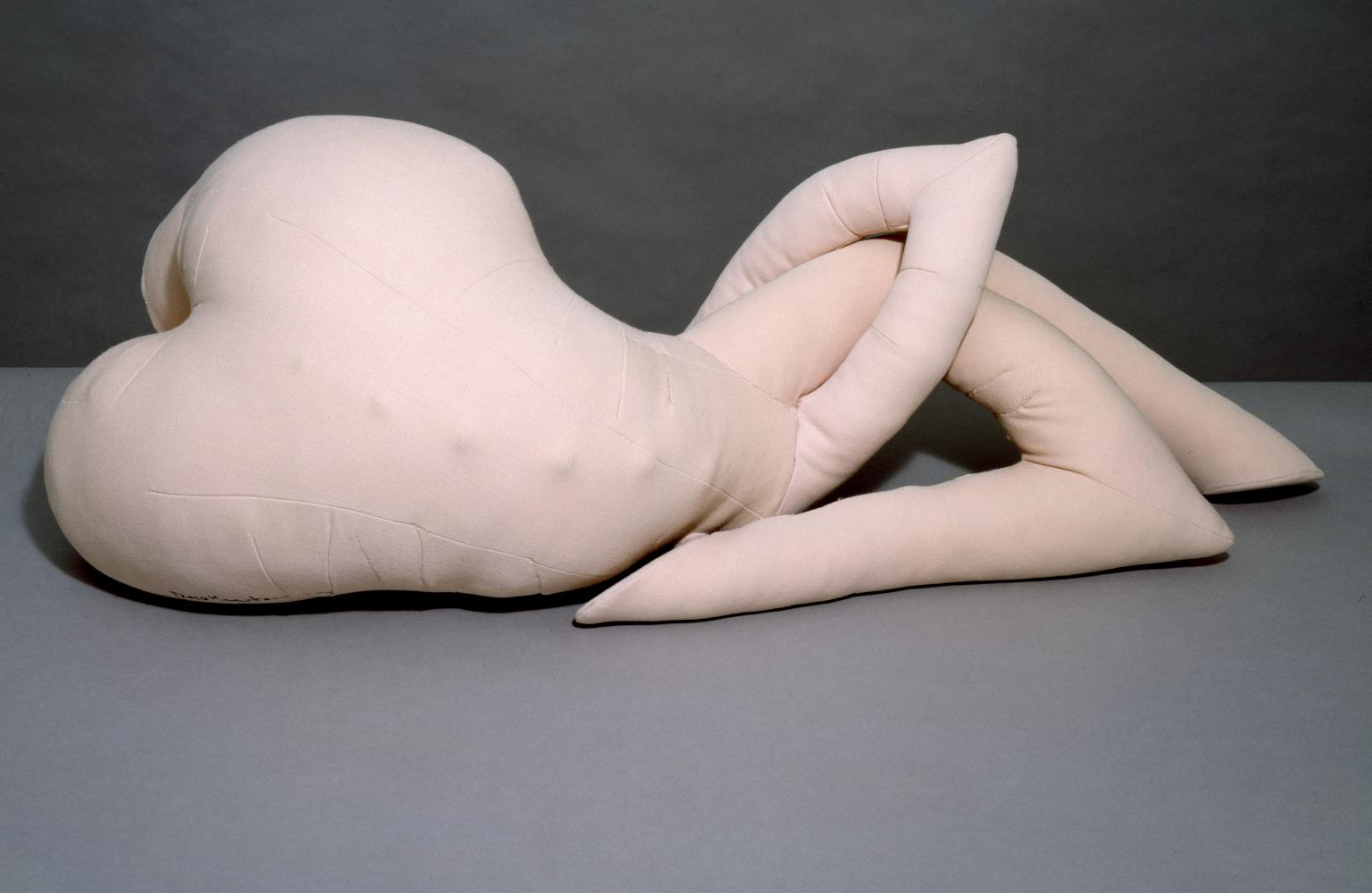

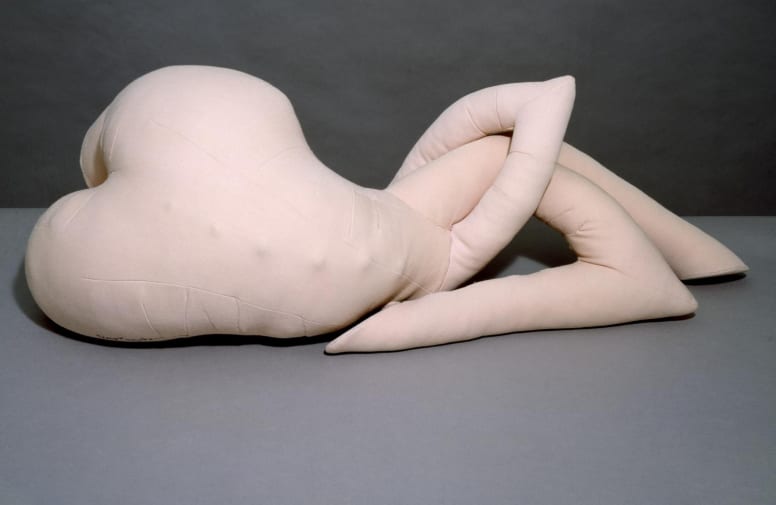

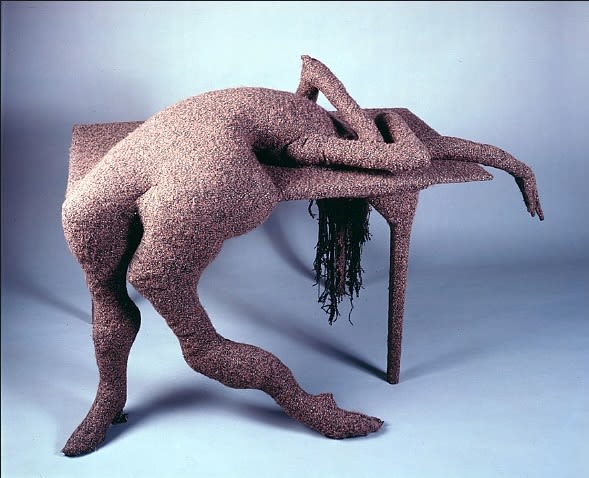

And then there are the similarities in their art practice. Tanning is described as a Surrealist. She created work that depicted "unknown but knowable states." Later she is described as an abstract artist, yet always suggestive of the female form. Bourgeois is described as Surrealist but is also affiliated with feminist art and Modernism. Both used many art forms and medium to depict their ideas. Tanning explored the female figure in the gothic. Bourgeois explored the psychoanalytic, especially the mother figure. Both "disappeared" mid-career. Both used writing and poetry to extend their art practice. Both had an animal familiar: Tanning used images of her dog in her work while Bourgeois used images of a spider in her work. Both made extensive use of the symbolism of doors and tables and used "rooms" to create art installations. Both used faceless human forms that are entangled, deformed and draped or suspended. Both created blind and deformed heads.

Where lies the trauma?

Tanning's childhood has been described as normal, happy, even boring. "Nothing happened but the wallpaper" said Tanning about the small town in Illinois where she grew up. She talked of how her imagination was fuelled by her childhood in small-town America and her interest in romantic literature, gothic novels and dance. In her autobiography, she described her paintings as "pirate maps, diagrams for mutiny", to escape the dullness of home.

Bourgeois' childhood has been described as disrupted by a philandering father and an ill mother. She recalls her father saying "I love you" repeatedly to her mother, despite infidelity. "He was the wolf, and she was the rational hare, forgiving and accepting him as he was." Bourgeois' diary entry "To be an artist is to guarantee to your fellow human that the wear and tear of living will not let you become a murderer" underlines the idea that Bourgeois made art to keep herself sane after suffering childhood trauma. Bourgeois was in therapy for many years, only halting the process on the death of her therapist. Maria Walsh in her book "Art and Psychoanalysis" (2012) talks of there being "no cure for the artist - but art can reconcile us to the traumatic nature of human experience, converting the sadistic impulses of the ego towards domination and war into a masochistic ethics of responsibility and desire." As Viv Albertine recently said about the Bourgeois quote above, "It means that creativity is a channel for your anger and your fury. A woman said it, and as a woman I believe it, because women do have a lot of anger and fury. More women should be creative-not only does the world need it, but the women need it."

What is interesting is that while Bourgeois claimed the reason she created art was to preserve her sanity, Tanning has always maintained that her childhood was idyllic and that allowed her the space to let her imagination take flight. How is it that two minds, creating some uncannily similar art, operate in such opposing spaces?

There has been an anecdotal link between artists and "madness" for centuries. Definitions of terms such as "mad" and "madness" have historical context and are fraught with meaning. Mental health is a serious and ubiquitous issue that has always underlined the art world. The term "mad" could refer to very serious illness, it could refer to eccentricity, it could refer to anger. It has been used to dismiss serious illness as trivial. It has many meanings and its use depends on the individual's perspective. There is that image of the strange and probably starving artist in the garret, the "mad-man" who creates profound and wonderful art. Maybe this artist did suffer with serious mental illness, maybe he was just eccentric.

For women, the historical image is quite different. It was never acceptable for a woman to be that eccentric. It is possible that over the centuries, many wonderful women artist’s works remained closely guarded inside the walls of psychiatric hospitals. Artists from Camille Claudel (1864-1943) to Aloize Corbaz (1888-1964) to Mary Barnes (1923-2001) represent a few women that were institutionalized but had a powerful enough voice that enabled their works to resonate outside of those walls. As Albertine suggests in the aforementioned quote, “madness” could be mistaken for pure fury.

More recently, a number of psycho-biographic studies have been conducted to investigate the connection between art and mental health. Burch et al. in their paper “Schizotypy and creativity in visual artists” (2006) proved a link between mental disorder and visual artists (at Goldsmiths university) using the Oxford-Liverpool Inventory of Feelings and Experiences (O-LIFE) survey. Results found that the “visual artists group scored higher on measures of positive-schizotypy, disorganized schizotypy, asocial-schizotypy, neuroticism, openness and divergent thinking (uniqueness) than did the non-artist group and lower on agreeableness.” The relationship between creativity and schizotypy is discussed in the paper focusing on “unusual ideas and a propensity to endorse socially undesirable response.” In short, the paper perhaps proves that artists have a degree of “madness” that allows them to create original work with little care of being socially acceptable or accepted.

But does Tanning’s work offer a kind of proof that “madness” is not necessary to create strange, profound and wonderful art? What might be necessary instead is the freedom to access the whole of one’s mind. Artists talk of a “creative zone” that disallows thinking, and is described as “being”. This freedom to access the “zone” might also allow us to access the subconsciousness and the “madness” that lies within. Tanning herself says, “Art has always been the raft onto which we climb to save our sanity.” Do artists generally have greater access to their subconscious minds - does this make them more creative and more “mad”?

Virginia Woolf famously insisted in “A Room of One’s Own” that “a woman must have money and a room of her own if she is to write fiction.” She seems to understand the need artists have to create, and the impact not creating has: “When, however, one reads of a witch being ducked, of a woman possessed by devils, of a wise woman selling herbs, or even of a very remarkable man who had a mother, then I think we are on the track of a lost novelist, a suppressed poet, of some mute and inglorious Jane Austen, some Emily Bronte who dashed her brains out on the moor or mopped and mowed about the highways crazed with the torture that her gift had put her to. Indeed, I would venture to guess that Anon, who wrote so many poems without signing them, was often a woman.”

Does sanity rely on creativity, or does creativity rely on “madness”?

For Tanning, Bourgeois, Woolf, Albertine and Walsh the need to create is a survival mechanism, the sanity of the individual relies on allowing that person the space and time to create. Without that space and time, the individual goes “mad”. For Burch et al. there is a link between creative individuals and measures of schizotypy, that creative people are typically more “mad”. Tanning’s creativity relied on her ability to “look beyond the obvious” into a “mad” world. The idea that Tanning had the freedom of space and time, that she did not need to fight to be able to create, potentially means that she never had to face the “highways crazed with the torture that her gift had put her to”.

Does creativity rely on “madness”? Probably not, although it probably does rely on the luxury of freedom, time, space and money. Sanity, however, might rely on the provision of these luxuries.

Find out more about Philippa's work on her webite: www.philippakate.com

Read more about the Post-Grad Community at UAL