Article by Cecilia Ceccherini, AER artist in residence at Mahler & LeWitt Studios, Spoleto, Italy 2020.

Arriving in Spoleto, I immediately felt at home: the thick limestone bricks, cream walls, dark-green cypresses, and serpentine alleys. I was born and raised in Tuscany, a region which shares a border with Umbria, and so this landscape sounded deeply familiar. Guy Robertson, the curator of the residency program, brought me to my apartment and showed me the studios, which were at the same time elegant, rustic and comfortable. I left my materials in a room in Sol LeWitt’s former studio, where I was to stay and work. That space was still awash with his presence. Prints he had made hung on one wall and the drawers of the cabinets were still full of his tools.

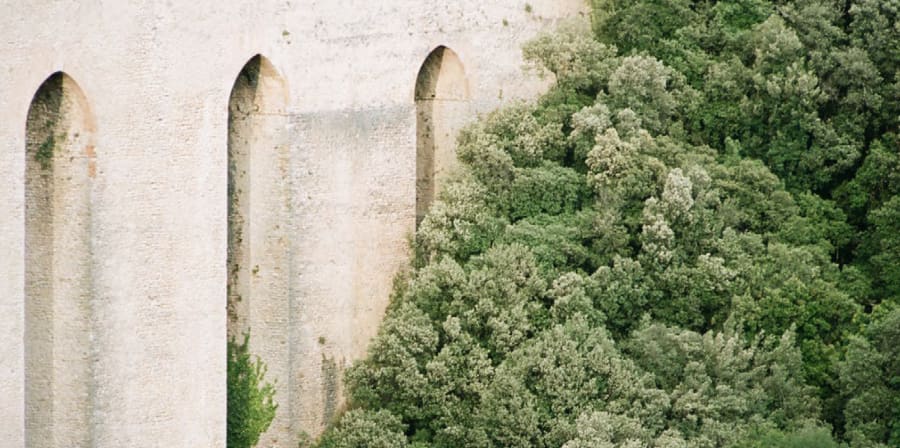

Sol LeWitt, a pioneer of conceptual art, first came to Spoleto in 1971, invited by his gallerist Marilena Bonomo. He had already thought a great deal about Italian art, but its influence would now take a firmer grip. Beyond his interest in antique and Renaissance art, he mixed with and looked at the work of contemporary Italian artists, including Boetti, Kounellis, Paolini, Merz, and Penone, amongst others. In the 1980s he ‘discovered’ colours in the frescoes scattered around Spoleto and began deploying them in his own work. His daily walk to his studio in Spoleto took him from his home on Monteluco – the dark-green, forested hillside opposite the medieval town – across the aqueduct that links the two hills. Currently this bridge is closed for conservation purposes, and the direct connection between the forest and the urban environment is temporarily interrupted.

The day after I arrived, I decided to go for a walk on the 'giro', a path that rings around the Rocca Albornoziana, the fortress at the top of Spoleto, and brings you to the aqueduct. The path begins with a birds-eye-view of the Duomo (in which the astonishing frescoes, Scenes from the Life of the Virgin Mary, by Filippo Lippi are preserved) and continues with a wider view of Spoleto's surrounding valley. Then, all of a sudden, you find yourself in front of a curly, dense blanket of trees that covers Monteluco: the different shades of green lend the hillside an infinite rhythm. And then, the aqueduct appears.

Next to it, a plate recalled Goethe’s memories:

Sono salito a Spoleto e sono anche stato sull’acquedotto, che nel tempo stesso è ponte fra una montagna e l’altra. Le dieci arcate che sovrastano a tutta la valle, costruite di mattoni, resistono sicure attraverso i secoli, mentre l’acqua scorre perenne da un capo all’altro di Spoleto. È questa la terza opera degli antichi che ho innanzi a me e di cui osservo la stessa impronta, sempre grandiosa. L’arte architettonica degli antichi è veramente una seconda natura, che opera conforme agli usi e agli scopi civili. È così che sorge l’anfiteatro, il tempio, l’acquedotto. E adesso soltanto sento con quanta ragione ho sempre trovato detestabili le costruzioni fatte a capricciocose tutte nate morte, perché ciò che veramente non ha una sua ragione di esistere, non ha vita, e non può essere grande, né diventare grande.

In Goethe’s writings, antique art and architecture appear as a 'second nature', connecting humans with the non-human world, rising in harmony with the surrounding environment. His statement triggered thoughts in my mind: What does it really mean to make art for the environment? What separates us from other living beings? Has a ‘bridge’, between humans and nature, been destroyed or, at least, has a passage been disrupted? How important is it to make art, today, that is more than a caprice and is, moreover, a socio-political act?

My practice aims to address these questions by combining a practical understanding of the history and technologies of design, with the generative potentiality of conceptual art (as Sol LeWitt wrote, “Perception of ideas leads to new ideas”). In so doing, I ask another question: How can we change our relationship with materials, resources and ways of production in order to design a more sustainable future?

Research

The rugs and textile pieces which I make explore the ancient traditions of tapestry weaving: as a 'slow' technology, weaving permits a different, more profound relationship to emerge between humans and natural resources. I understand my textiles as being portals of connection between humans and the natural world. The textiles communicate this connection not only through their aesthetics and presentation, but by making use of specific materials and processes: for example, the wool and natural dyes I use are sourced from producers who have a direct relationship with and thorough understanding of the plants and animals with which they work. With this in mind, during my residency in Spoleto I travelled across Umbria and the Marche generating bonds with artisans who have developed expertise in sustainable textile making and natural dyeing.

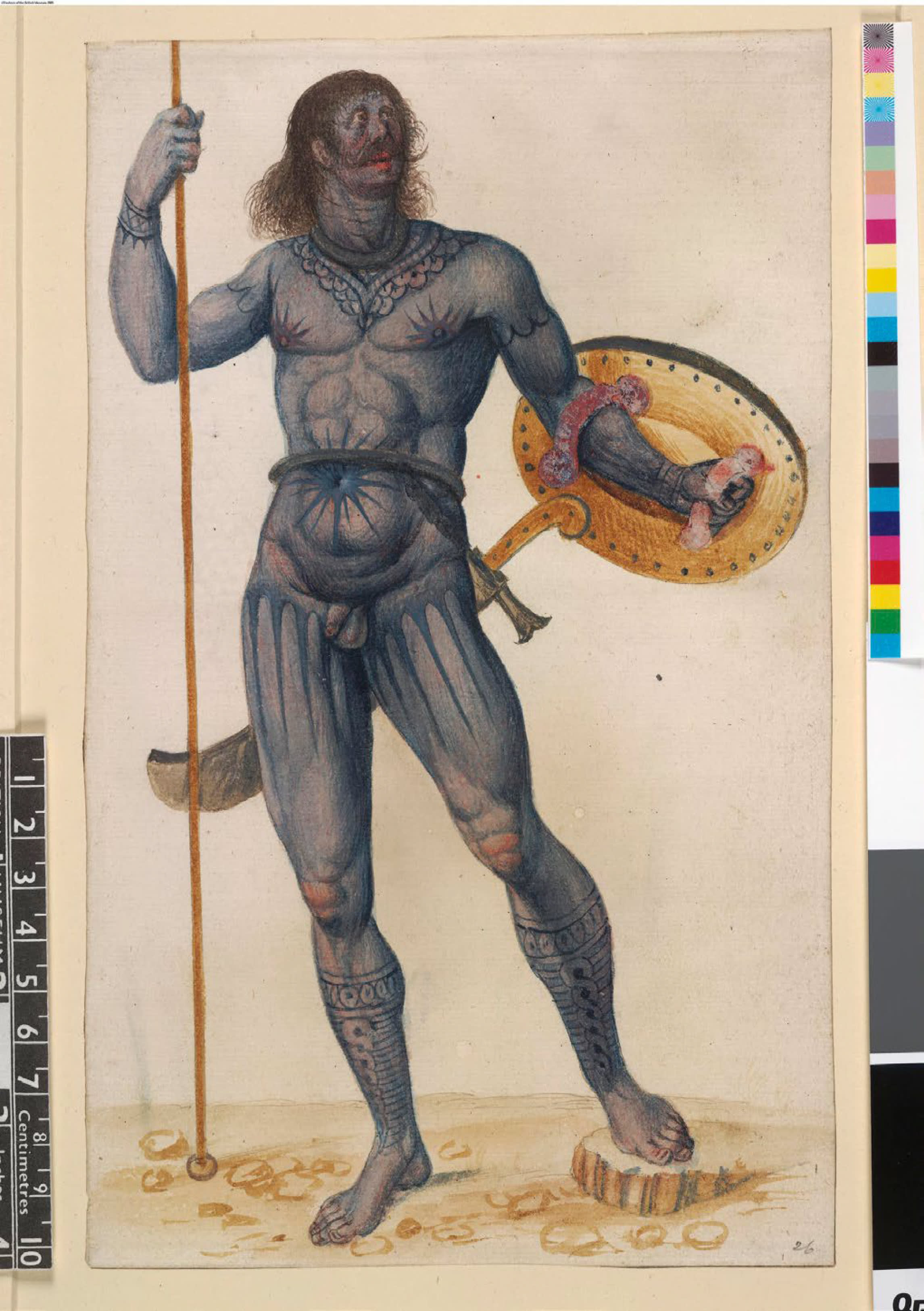

Owing to its historical relationship with the region around Spoleto, I developed a particular interest in an ancient tinctorial plant, called woad, which was cultivated and used to dye blues before indigo began to be imported from India. Isatis tinctoria, the scientific name of woad, was an important source of blue in much of Europe during the medieval period. In Roman culture, blue was considered a negative colour because it was used by people they viewed as barbarians, like the Picts, who painted their bodies with pigments derived from woad. Only during the medieval era did woad increase in popularity. Eventually, it was cultivated in such abundance around Thuringia in Germany and across southern France, creating a prosperous trade and generating significant wealth, that these territories became known as Pays de Cocagne (which translates to 'lands of plenty'). A cocagne was also the name of the loaf of soaked leaves which was processed in the first step of woad production. Around the XIV and XV century, the woad market reached Italy, and this tinctorial plant was harvested and processed in Umbria, the Marche, Toscana, Piemonte, and Liguria. It was used not only as a dye for textiles but also in ceramics, illuminated manuscripts, and fresco painting. The blue in some paintings by Piero Della Francesca, for instance, is thought to have come from woad – his father was a successful woad merchant based in Tuscany.

-

Daniel Gottfried Schrebers, woad illustration from the book der Rechte Doctors : historische, physische und öconomische Beschreibung des Waidtes : dessen Baues, Bereitung und Gebrauches zum Färben, auch Handels mit selbigen überhaupt, besonders aber in Thüringen : mit Beylagen, und einem Anhange drey- er alter Schriften (1752)

-

John White, drawing, (1585-1593 ) A ‘Pict warrior’; nude with stained and painted body, with shield, scimitar and spear Pen and brown ink and watercolour and bodycolour over graphite, touched with white (oxidised) © The Trustees of the British Museum

After this period of wide usage, in the XVI century Isatis tinctoria was promptly replaced with Indigofera tinctoria, a plant imported from India that was cheaper and easier to process. Woad ‘disappeared’ for several centuries. It resurfaced at the beginning of the XIX century, when the Napoleonic Wars disrupted trade routes with India. Blue pigment, from woad, was once again produced in France. Finally, in 1897, this ancient, natural dye was entirely replaced by synthetic dyes derived from indigo, which enabled the production of blue textiles on an industrial scale.

Intrigued by the story of this ‘endangered’ knowledge, I researched natural dyeing initiatives in Umbria. I discovered a project called FICOPROARG, which was developed by the University of Perugia, amongst other partners, and which carried out research in the stability of natural dyes, with a view to increasing their commercial prospects. Through this program I was put in contact with two experts, Alessandro Butta and Marco Fantuzzi.

I visited and worked with Alessandro on two occasions during my residency in Spoleto. He moved to the Marche in the 1980s and, together with twelve other families, founded an agricultural cooperative and community in Montefiore dell’Aso. In 1995 they started researching tinctorial plants, harvesting them, and producing natural pigments. They were particularly intrigued by woad, because it had, historically, been produced in the territory, and they became one of the few contemporary woad cultivators in Italy. Alessandro has participated in a range of related projects, including TUN (Tessile Umbro Naturale), and he has collaborated with various Universities including Pisa and Università Politecnica delle Marche. I had hoped to see a woad dyeing demonstration, but, unfortunately, the harvest that year was scarce, due to a sudden and unexpected hail storm that destroyed part of the cultivation – if you work with natural resources you have to be ready to alter the path of your project. Instead, we dyed with organic indigo: although the source plant is different, the process of dyeing is the same. Alessandro also gifted me a large amount of wool which he had previously dyed with woad.

During my residency I made several other research trips across Umbria and the Marche. I became fascinated by stories regarding the attempt to repopulate Sopravissana, an historic and now endangered breed of sheep indigenous to the local Appennini mountains. Originally appreciated for their soft and fine wool, the Sopravissana were known for their versatility: they had what is known as a 'triple attitude', producing wool, meat, and milk. Its multi-functionality aided the survival of local communities who struggled with the tough geography of their territory. Over time the Sopravissana lost its relevance due to the general decline of pastoralism and the push of the market towards more productive specialized breeds. In the last twenty years, breeders have been working with local businesses and research departments to repopulate this endangered species in order to maintain the local biodiversity. I visited Francesca Chiacchiarini, a woman who breeds Sopravissana sheep in Pettino, a village in the countryside near Spoleto. She told me about the challenges of being a sheep breeder and explained why it is important to keep this knowledge and rural experience alive.

I also visited Maridiana Alpaca, a farmhouse that breeds Alpacas and one of the partners involved in the Tessile Umbro Naturale (TUN) project. I had a tour inside Giuditta Brozzetti’s workshop in Perugia, one of the few places that continues to weave the traditional, patterned Umbrian cloth, Tovaglia Perugina, under the direction of Marta Cucchia. Finally, I also visited the Museo Della Canapa in Sant’Anatolia di Narco, where the director, Glenda Giampaoli, supported me by offering, on loan, a loom.

Research

My research moved in tandem with my making: my studio practice involves drawing, writing, and weaving. I follow my ideas from sketchbooks on to the walls, and from the walls to the loom. Using material and symbolic representations, I try to develop tapestries which bind together my own experiences, whilst narrating histories of traditional and local crafts.

The new piece I wove in Spoleto used the woad-dyed blue wool given to me by Alessandro. In order to make use of an entire batch of natural dye, fades in colour – from dark to light – naturally occur in the yarn produced and I make use of these shades on the planes of blue in the textile. Into this background I inserted ripples of white dots. The visual rhythms these fades and ripples enact, point to larger themes: environmental cycles and the revolutions of time. The patterns also brought to my mind Mettere al mondo il mondo (Bringing the world into the world) by Alighiero Boetti, one of the finest examples of his Biro works, in which white commas, appearing on a vast sea of ink, are clues for deciphering hidden messages.

Making

Taking inspiration from Sol LeWitt’s wall paintings in the Torre Bonomo and in the Eremo Santa Maria Maddalena on Monteluco, I started transferring my drawings onto the walls, crafting new kinds of portals that had some similar features to the tapestries. I made the inks for these wall drawings out of a mixture of natural pigments (woad for the blue, and the roots of rose madder – rubia tinctorium – to create a red known as Turkey red), Arabic gum, and honey, following a recipe given to me by Marco, an expert of natural dyes who collaborates with Alessandro.

For the Open Studios exhibition at the end of my residency I worked with the studio curators on the installation of new and recent work to create a space for imaginative reflection. We aimed to craft an environment that would allow the pieces to speak autonomously, but also in connection with each other. Mountains are lost oceans was the title of the final exhibition. The rugs, wall drawings and embroidered portals are seen as thresholds permitting connections: areas of continuity between human and non-human forces.

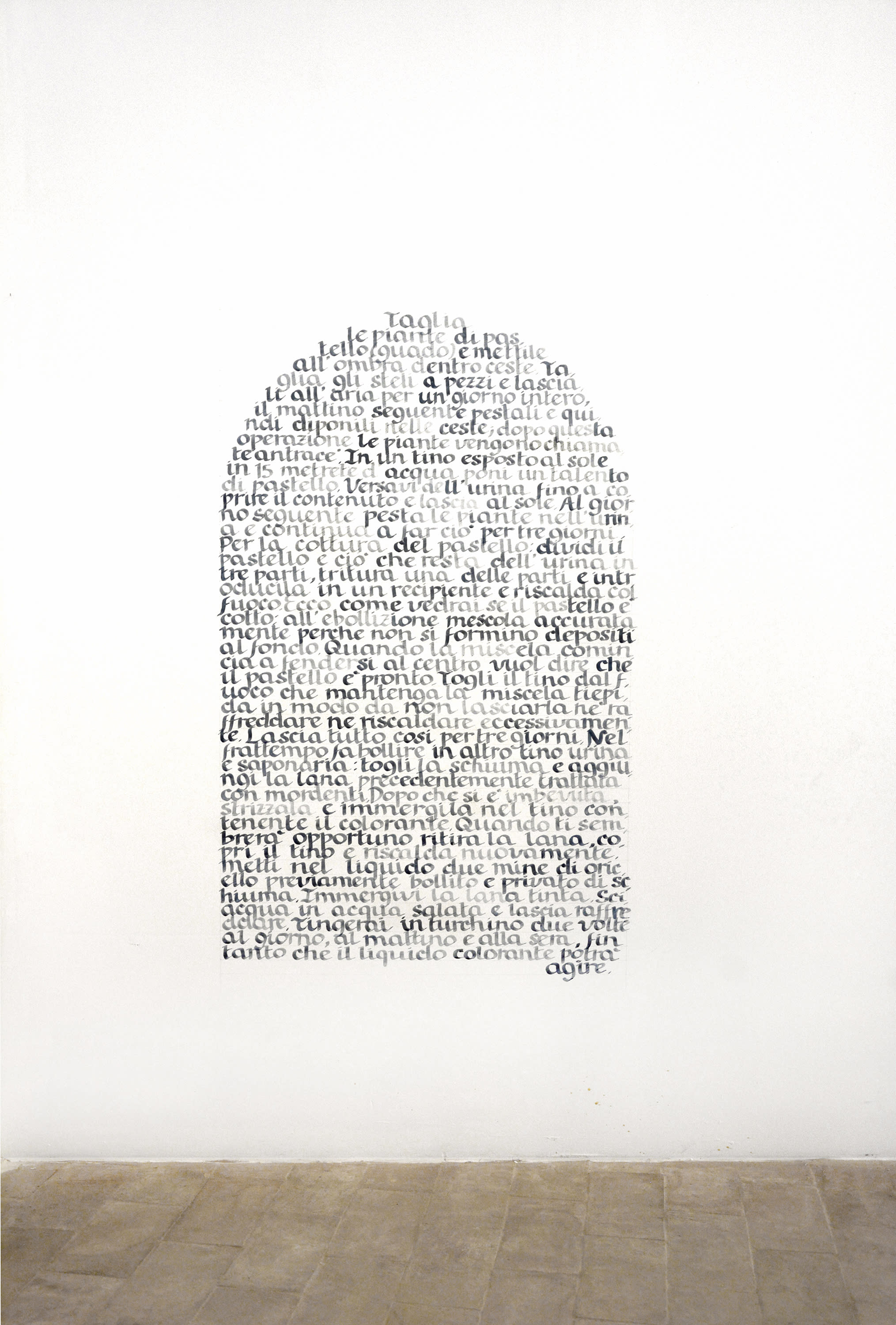

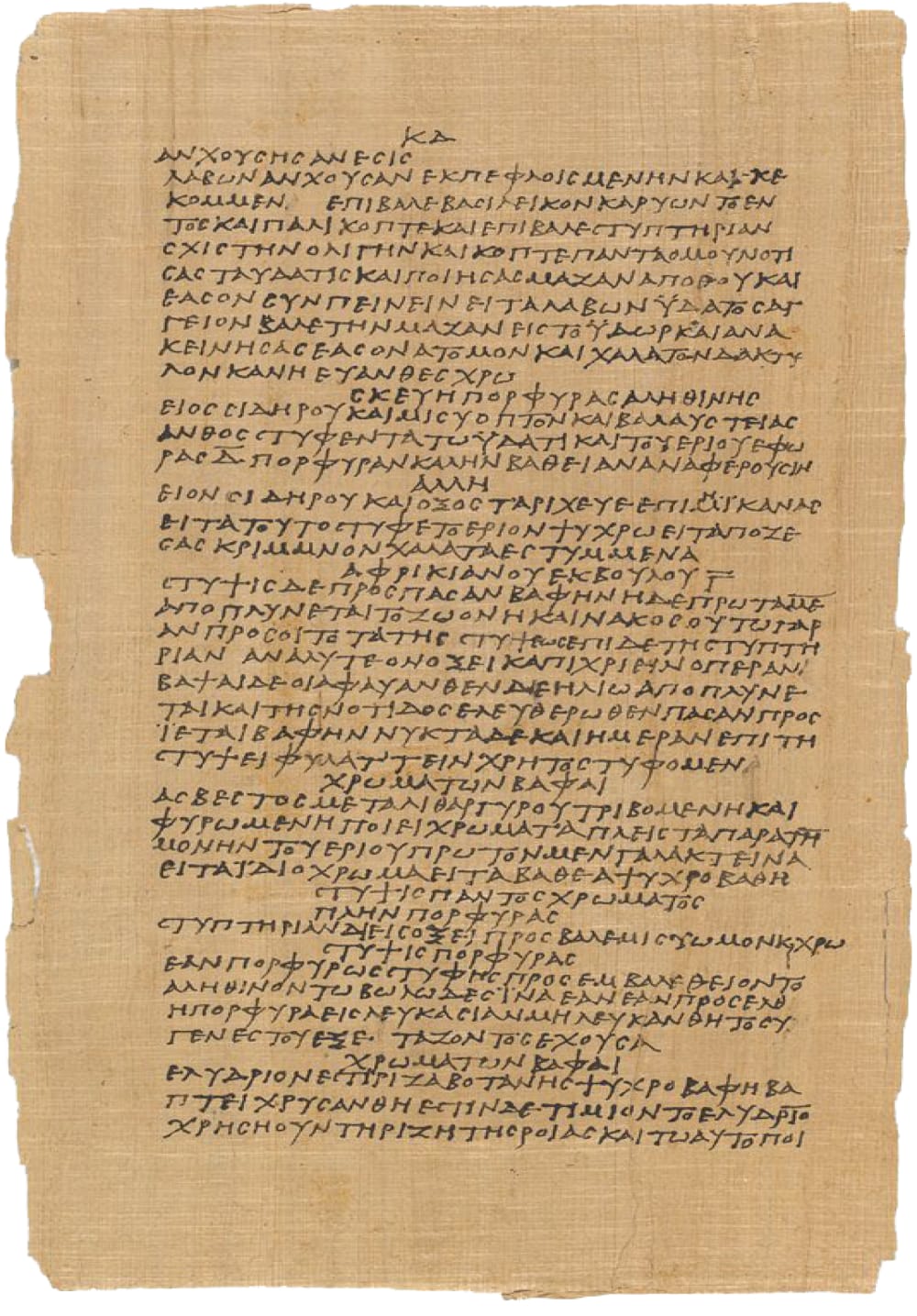

I drew up three calligraphic texts in pre-determined shapes on the walls. In a blue edicola, or window, I transcribed part of an ancient recipe for dyeing woad, taken from the Papyrus Graecus Holmiensis, a collection compiled in Egypt c.300 AD.

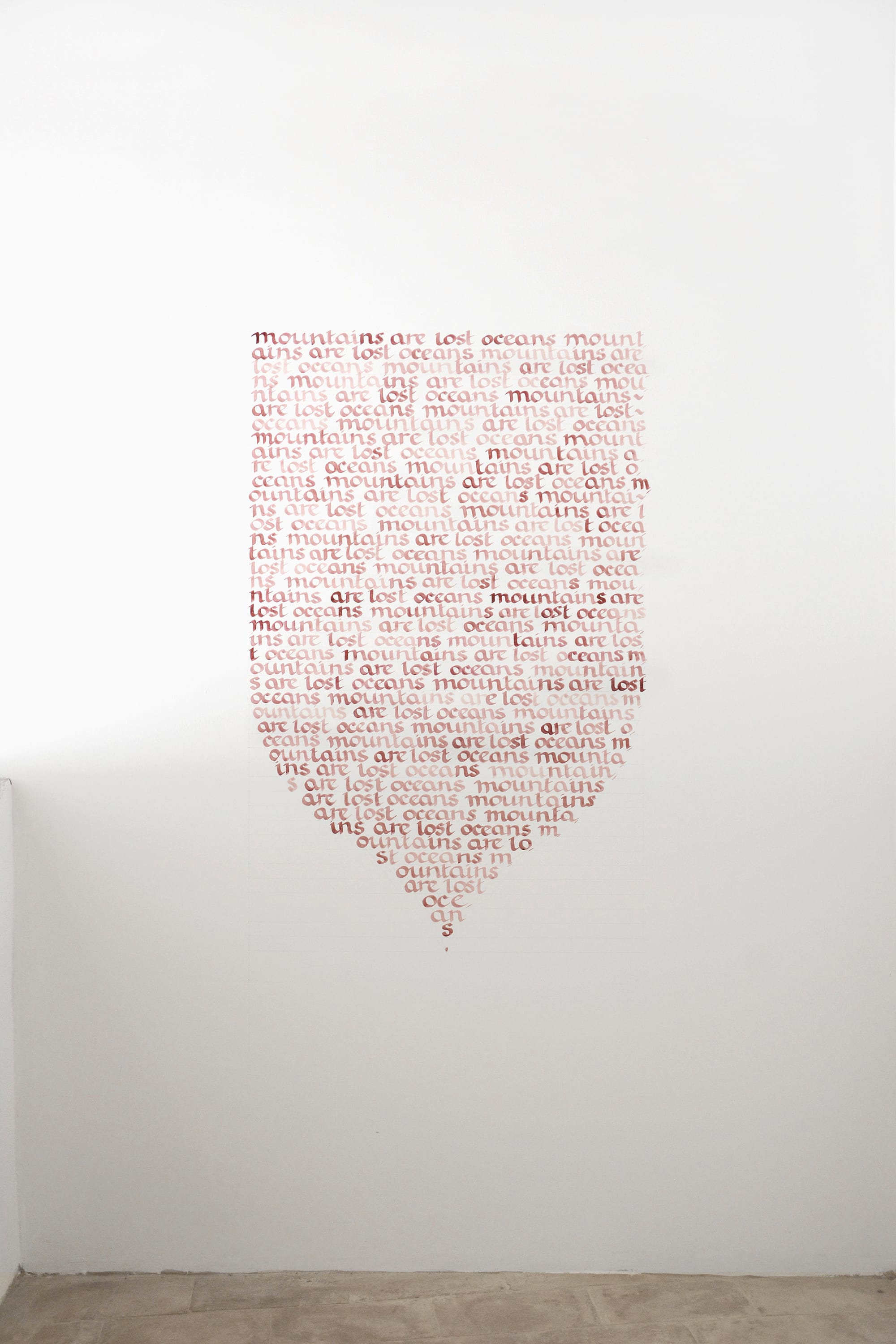

In a red, door-shaped drawing I repeated the phrase “mountains are lost oceans”: it read as a kind of mantra, generating a meditation upon the meaning of transformation.

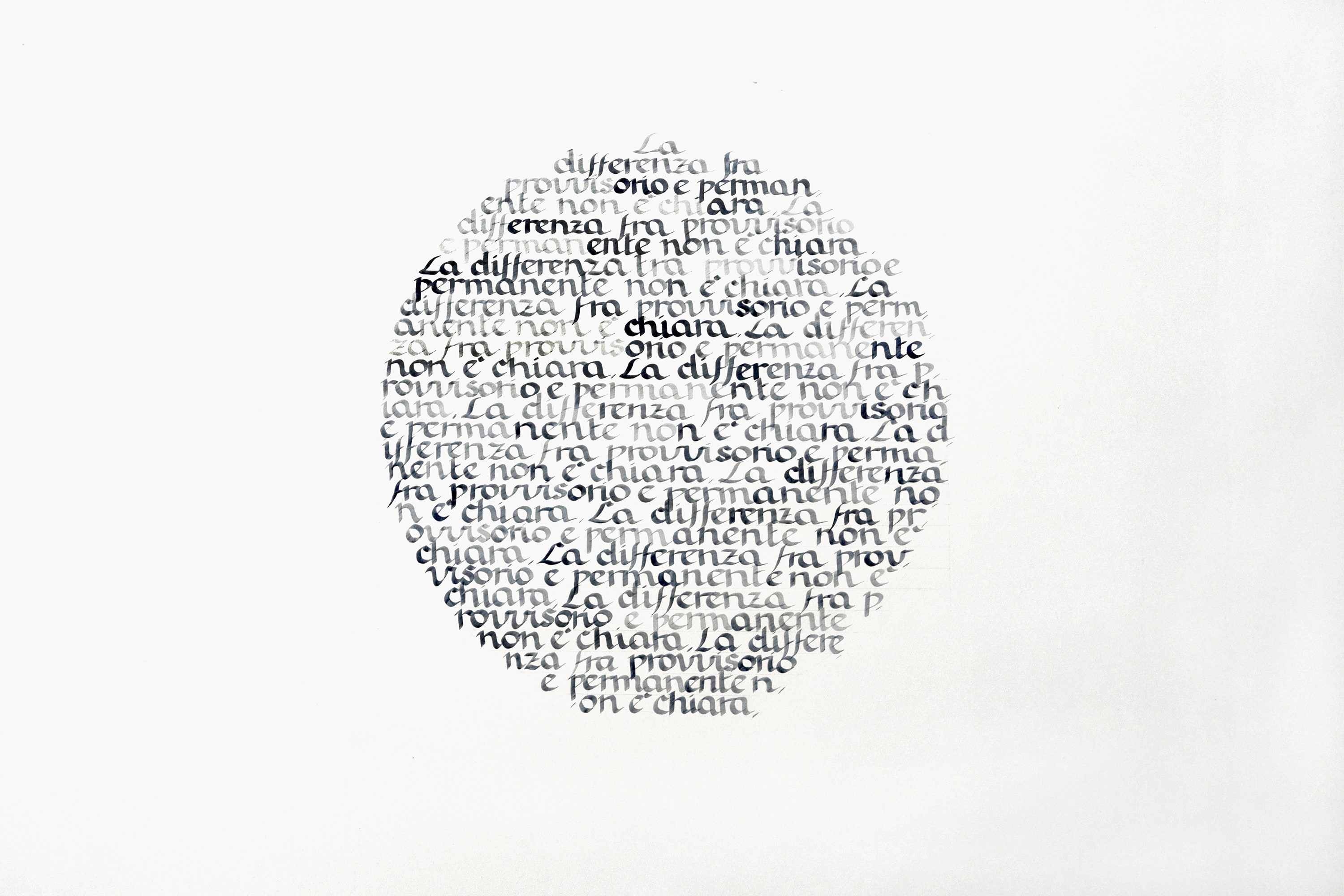

In a blue circle of text I repeated a line from a LeWitt interview with Andrea Miller-Keller. When he was asked about the impermanent nature of his wall paintings, he answered with a phrase that referred to an ontological dimension, rather than a practical one: “la differenza fra provvisorio e permanente non e chiara” (the difference between the ephemeral and the permanent is not clear).

When I read this statement, I felt a philosophical correspondence between it and the ideas in my exhibition.

The colour of each written sentence in my wall drawings fades as my brush gradually runs out of ink, only regaining strength when it is dipped again. This creates a sense of movement, similar to the shimmer of the moving surface of the sea, or those rhythms found in my tapestries.

The last element of the exhibition was an accompanying text, one of my own writings. Rather than trying to describe with words what the pieces were already attempting to say in a poetic language, I preferred to offer a more abstract text that would evoke, instead of explaining, my thoughts:

How do we exist if we don’t consider us in relation with the surrounding? What are we — as human beings — without an external space which defines our limits?

Can you really see your skin as a liminal surface that separates you from the outside?

We are just a variation on the theme of the earth’s own matter, we are planetary bodies and we were, are, or will be plants, animals, the soil or the sea. Is this scaring?

Can this be scaring as looking at an infinite dark sky, with no stars to find your way around?

Being without a compass can be deadly, being without the control of nature can paralyse.

What if we start imagining ourselves being in continuity with other living beings, as if a blade of grass could be one of my curly hair, as if you could be dissolved in a wave of the mediterranean, as if we were the stone of a cave, or a sheep’s fleece.

What stands on the threshold? Can you still perceive the interconnectedness — the entire network of relation between things?

I will stand on the threshold, where the unknown stands, to recover the mythical and symbolic thinking, that strive to form spiritual bonds between humanity and the surrounding world, shaping distance into the space required for devotion and reflection.

There is nothing to control, we just have to allow energy’s exchange.

Going back to one of my opening questions, what does it mean to make art for the environment? Personally, I consider the environment not only from a planetary view, but with an 'on-the-ground' perspective: art can be a medium and a practical way to connect the two. To understand, from a personal point of view, the enormous issues at hand. Approaching, from a practical perspective, how things are made and what resources are employed – to produce objects we use and consume – allows us to develop another form of care for the environment and its inhabitants. Maybe what we need is to “relearn multiple forms of curiosity”, to think of curiosity as, “an attunement to multispecies entanglement, complexity and the shimmer all around us.

Art and the imagination are political tools that allow everything to shimmer, lighting up new forms of action.

'Mountains are lost oceans' at Mahler & LeWitt Studios, Spoleto, 2020

-

Mountains are lost oceans, Installation view at Mahler&LeWitt Studios, Spoleto, 2020. Photo: Alice Mazzarella and Emanuele De Donno

-

Ritmo I - guado, Natural pigment gouache on wall, 130x83cm, Mahler&LeWitt Studios, Spoleto, 2020. Photo: Alice Mazzarella and Emanuele De Donno

-

Double passage door, Handwoven natural dyed wool (white natural, moretto, madder-dyed), flax, copper. Mahler&LeWitt Studios, Spoleto, 2020. Photo: Alice Mazzarella and Emanuele De Donno

-

Ritmo III - La differenza fra provvisorio e permanente non è chiara, Natural pigment gouache on wall, 80x80cm, Mahler&LeWitt Studios, Spoleto, 2020. Photo: Alice Mazzarella and Emanuele De Donno

-

Mountains are lost oceans, Installation view at Mahler&LeWitt Studios, Spoleto, 2020. Photo: Alice Mazzarella and Emanuele De Donno

-

Ricordati di essere gentile con te stesso e con gli altri, Natural woad-dyed wool, Mahler&LeWitt Studios, Spoleto, 2020. Photo: Alice Mazzarella and Emanuele De Donno

-

Mountains are lost oceans, Installation view at Mahler&LeWitt Studios, Spoleto, 2020. Photo: Alice Mazzarella and Emanuele De Donno

-

I see you shimmering, Handwoven natural dyed wool (white natural, madder-dyed, woad-dyed), flax, copper. Mahler&LeWitt Studios, Spoleto, 2020. Photo: Alice Mazzarella and Emanuele De Donno

-

Brindiamo alle future ceneri!, Handwoven natural dyed wool (white natural, moretto, madder-dyed), flax, copper. Mahler&LeWitt Studios, Spoleto, 2020. Photo: Alice Mazzarella and Emanuele De Donno

-

Ritmo II - mountains are lost oceans, Natural pigment gouache on wall, 130x83cm, Mahler&LeWitt Studios, Spoleto, 2020. Photo: Alice Mazzarella and Emanuele De Donno

My thanks

I would like to thank Lucy Orta and Camilla Palestra (UAL Centre for Sustainable Fashion), Abigail Fletcher, (Post-Grad Community) Guy Robertson, Tommaso Faraci and Mahler & LeWitt Studios for awarding me the residency and following me during this time.

Infinite thanks also to: Noemi e Gianni Berna, Alessandro Butta, Marta Cucchia, Marco Fantuzzi, Glenda Giampaoli, Francesca Chiacchiarini, Carmen Moreno and the group artists, writers and curators who shared with me this beautiful time in Spoleto.

Cecilia Ceccherini studied MA Textile Design at Chelsea Colege of Arts and graduated with Merit in 2019.

More about the AER Residency

The Art for the Environment Residency Programme (AER) provides UAL graduates with the opportunity to apply for a 2 to 4 week fully funded residency at one of our internationally renowned host institutions, to explore concerns that define the 21st century – biodiversity, environmental sustainability, social economy and human rights.

Founded in 2015, internationally acclaimed artist Professor Lucy Orta, UAL Chair of Art for the Environment – Centre for Sustainable Fashion, launched the programme in partnership with international residency programmes and UAL Post-Grad Community.