This blog has been written by one of the Archives and Special Collections Centre volunteers, Joy Cuff, who worked with Stanley Kubrick on 2001: A Space Odyssey and has donated some of her own materials to the Joy Cuff Archive. Our volunteers are working with us remotely during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Meeting Stanley

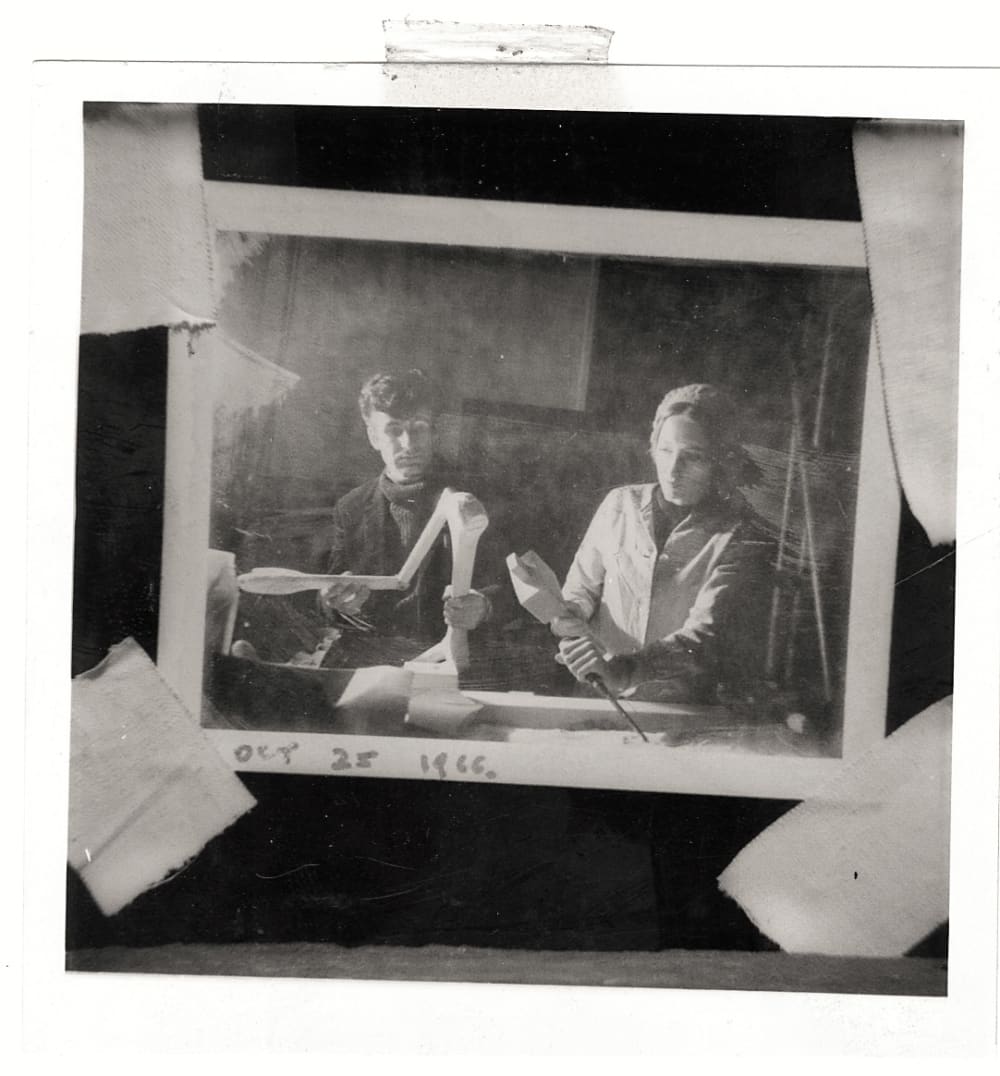

My first meeting with Stanley happened on my first day on the set. In 1966 there was no digital imaging and no social media, so I didn’t really know what he looked like. I had seen Spartacus and Paths of Glory - I knew the name but not the face. In walked three men to the stage I had started work on; they were all the same height, looked similar ages, all dressed in navy blue and, once they approached speaking to each other, were all American. The one in the middle stepped forward and put his hand out to shake mine, ‘hi’ was the greeting - over fifty years on I can’t remember the following conversation! I was far too nervous.

He then started talking to the technicians with him, and there was the beginning of a table top model that I was working on which took my attention. The model had been attempted by various people. My initial contract (£16 a week) was for two weeks, and in this time I had to prove I could come up with the work. I did start a model, and after the two weeks an open-ended contract with £20 a week was handed to me. This was a big wage, each Friday received in cash in a brown envelope.

Stanley Kubrick was a known ‘workaholic’; totally immersed in his creativity, he was single focused. But he was a gentle person, who could occasionally be seen with his daughter sitting on his knee while on set near the centrifuge.

Follow us

Contact us

Working on 2001: A Space Odyssey

I didn’t find working difficult, it was exciting and so absorbing working on 2001. Stanley was very interested in talking to his workers on the film – our opinions were asked. He was very respectful of his staff, but he didn’t suffer fools lightly. He was totally involved in his film making, and expected his ‘team’ to feel the same. If 'overtime' was called, it could be called at the last minute. ‘You sold your soul to the film’ we used to say.

I was often involved in meetings with the art director Tony Masters and Special Effect technicians Con Pederson and Doug Trumbull, while Stanley questioned and gleaned ideas from the discussions - nowadays it would be referred to as brain-storming. At one of these meetings it was discussed how the substance of the moon surface should appear – soft, hard, spongy, or dusty. Collectively, it was decided to make the surface appear like hard rock, but with a dusty appearance. At this time there had not been a moon landing with photos to verify the surface, that was not until 1969 (the year after the film's release). For many years there was strange conspiracy theory that Kubrick helped to fake the USA’s moon landing, based on the moon models produced for 2001 looking so realistic. How we produced the moonscapes wasn’t spoken of for years and years, it is not documented in any early accounts of the film making.

The iconic matte shot of the astronauts entering the pit to investigate the monolith was shot on a Sunday. The matte was put together on the original film, and the live action had been shot at Shepperton on the ‘H stage’ as Stanley needed this space for the pit (the ‘H Stage’ was the largest stage at Shepperton studios, 45 feet high and 30,000 square feet of space, along with an interior tank 25ft x 12ft x 3ft).

In the archive one day, an archivist who had been looking through the 3”x5” library cards (Stanley kept these on his desk, and wrote notes to remind himself of thoughts or subjects) showed me that one read ‘see Joy tomorrow’ – it was dated March. I think back 40 years, and I can remember Stanley coming on set while I was working. He usually arrived on set to see the development of the work, or check camera set up for shooting, but this time he asked if I knew of a sculptor who might be interested in coming in to work? Well, as it happened one of my best friends was Lizzie, a struggling sculptor– so I recommended Liz Moore and she came in to be interviewed. Lizzie joined the team; her job was to sculpt the Star Child, working with Tony Masters who had envisaged the concept.

As I was writing this blog, my mobile rang and it was Estelle - Liz Moore’s sister. We of course started talking about Lizzie. Lizzie’s studio was in the attic at the family home in Ashtead, where she lived with her mother, grandmother and two half sisters. The star child was made away from MGM studios, and kept a secret until it was finished and cast in wax for the filming. Liz also worked on the monkey masks and body costumes, and another memory from Estelle was that a small monkey was bought to the studio at their house in Ashtead for Liz to study how it moved, and how the hair grew on its body etc. I do think this demonstrates the attention to detail that Stanley afforded his crew. Often research had to be achieved by photos, but there is nothing like the real thing.

Film release and credits

Stanley was also one of the first directors to acknowledge his workforce by attributing credits. To my great surprise, my screen credit can be found on a large screen credit card in the Stanley Kubrick Archive. This was unfortunately pulled by MGM when the rough cut was screened to them. My name was on a card which also contained MGM's craftsmen and technicians, who Stanley had felt worthy of a credit. I feel appreciated knowing that he gave me a credit. I was part of the giant jigsaw puzzle that I feel describes the making of a film. The director’s job is to ‘compose’ the film, and his tools are his workforce. However, at this time MGM did not allow their own personnel to be credited on film. All studios worked like this, this is why the amazing matte artists who painted the glasses the 1930–1960’s were not credited.

I did have a couple of screen credits later in my career, and on one occasion I had taken my youngest son, Thomas, with his friend to see the Adventures of Baron Munchausen directed by Terry Gilliam. At the end I always sat to watch the credits, enjoying seeing the names of technicians I have worked with, and my name came up for Visual Effects Matte Painter. A credit is mostly secured in the contracts, but for this film it was a surprise. Seeing my name, Thomas jumped up and shouted to the auditorium ‘that’s my mum!’ - that makes you feel good! I used to call this 'my other life'.

I didn’t see a rough cut of 2001 or a private view, my first viewing was at Leister Square Odeon in 65mm. The start made me tingle, the music had a very emotional effect on me and still does; I have seen this film many times, and I feel so fortunate to have been ‘in the right place at the right time. When I watch the film I am very critical, as I am with all my work. I look for pieces of the set which look man-made, any image that gives away the fact that the moon sets are often 5ft by 3 ft. They stood up to the 65mm on big screen. It is a small part of whole picture, like having the right colours and brush strokes in a painting. Looking back, sometimes can’t believe I actually built those sets - I am sure another artist would understand the feeling, I can complete a painting and not remember how I did it. Working is sometimes a subconscious act of creativity.

The Stanley Kubrick Archive and Joy Cuff Archive can be accessed by appointment in the Archives and Special Collections Centre, see our website for further information.