By Rashmi Shankar, MA Media, Communications and Critical Practice student at London College of Communication and part of on the mend, a creative studio which provides bespoke events, workshops and artworks to educate people on the societal impacts on health and well-being. We provide a platform to empower those under-represented by the current healthcare system. We’re the only creative studio in the UK to focus solely on health awareness and equality.

As students in creative courses, we constantly put ourselves in others’ shoes. We try to imagine how they live, how they use things or how they don’t use things. Because only by knowing their lives, we are able to create in a way that makes these lives better. Unfortunately, our imagination very often fails to include disabilities.

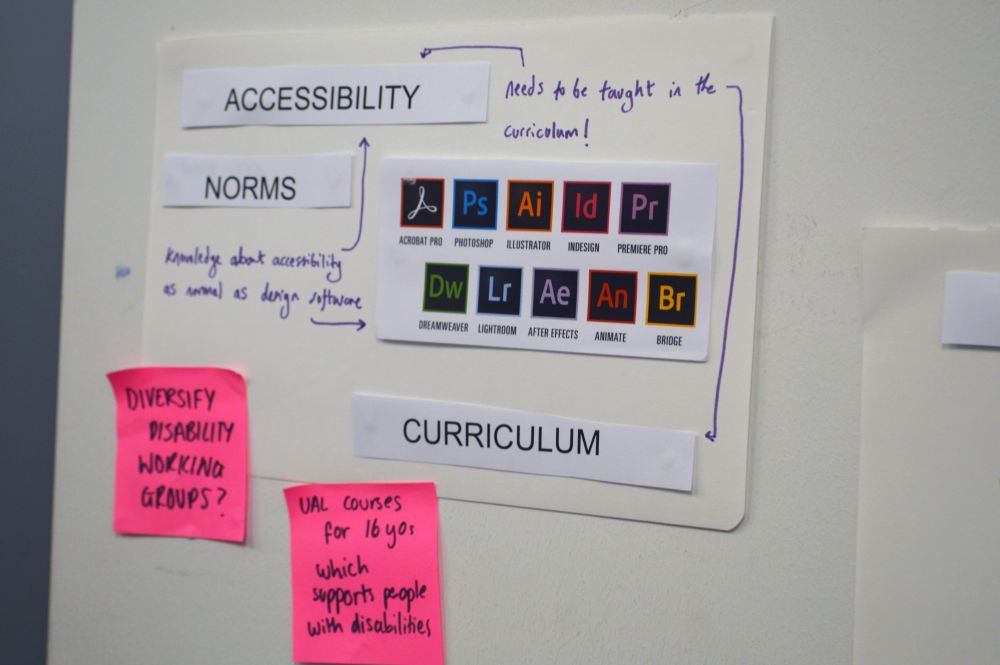

This was the second time ‘on the mend’ had received funding from Post-Grad Community Fund, the first being our debut event at Tate Exchange. This time, our funding was to produce our concept project, ‘Fonts with Feelings’, which aimed to enable those visually-impaired to experience differences in fonts and their designs. However, as a team with no visual impairment, our understanding of the lives of our audience was dangerously limited. Conversations with the UAL Disability Service, academics and students soon brought us the realisation that this is not exclusive to us. As students of the largest art and design postgraduate community in Europe at UAL, we realised that our education should equip us better for this topic. The opportunity to run a Pop-up Common Room event, gave us the chance to open up this conversation to other students across other UAL colleges and disciplines.

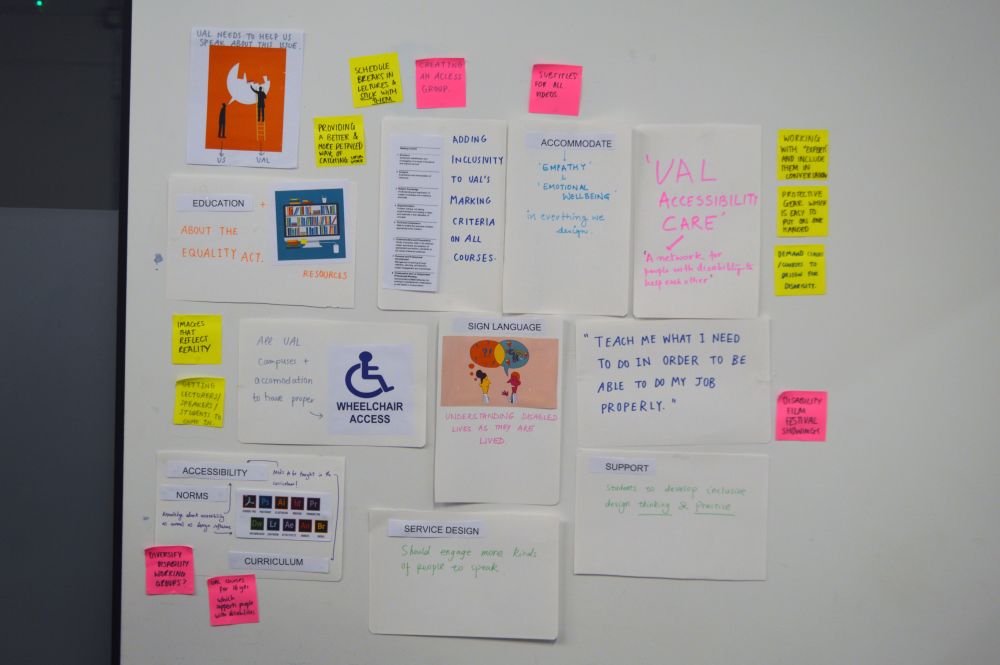

Workshop photos

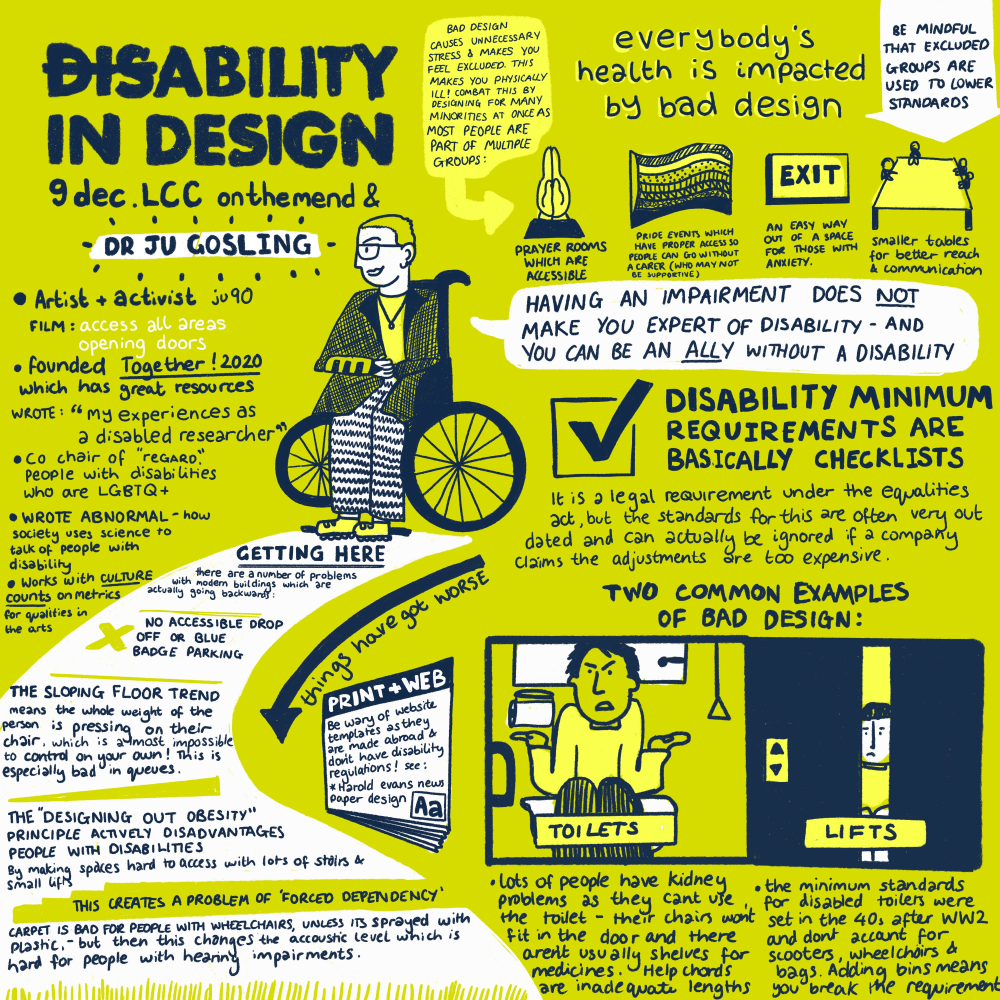

Disability in Design became a platform to identify gaps in learning and subsequently teaching, and build a manifesto that we would share with UAL, to make inclusivity and accessibility an integral part of our design thinking. And as all attendees of our event would agree, our guest speaker, Dr Ju Gosling got us perfectly placed to begin. Known as Ju90, Dr Gosling is a web artist and academic who works in the intersections of disability, queerness and the arts. We met her at a workshop where she spoke about Together! CIC, a collective of disabled artists of which Dr Gosling is artistic director.

From getting into the building to using an accessible toilet, Dr Gosling explained that what is usually considered accessible is barely even functional, most of the time. For wheelchair users, carpeted floors mean needing extra upper body strength to pull themselves across, and sloping floors are almost impossible to control on their own. Accessible toilets at their best have doors big enough for wheelchairs, but help chords don’t touch the floor, and there’s no medicine cabinets or closed bins for catheters and colostomy bags.

The principle of ‘designing out fatness’, which involves adding stairs and small lifts in spaces, actively disadvantages people with disabilities. Additionally, there are several kinds of disabilities and steps that might be beneficial to some and not others (for instance, carpets sprayed with plastic are more accessible for wheelchairs but hamper acoustic levels of the space which impacts those with learning disabilities). As we understood, the design of something affects greatly the people that can use them, but as Dr Gosling said, “everybody’s health is impacted by bad design”.

Here are some learning from the event, which will also be a part of our manifesto:

- As per the Equality Act of 2010 in the UK, disability is a ‘protected characteristic’, discrimination against which it is against the law. To be compliant with the law would make our designs inclusive and accessible.

- However, we must not stop at maintaining minimum legal standards. It is important to note that several legal standards are old hence outdated and we need to question and modify them to design better.

- Disability is seen as a permanent state, but it isn’t and there are several kinds of impairment. Most of us will face impairment of some kind in our lives, and design needs to be inclusive and flexible to accommodate the changing needs of people.

- Disabilities can likely lead to more disabilities (several wheelchair users end up with kidney failure due to not drinking enough water to avoid toilets) and “accessible designs” can create ‘forced dependency’. Some disabled people can have health issues but not all, and sometimes the ability to not access spaces meant for them causes emotional stress. Look further and ask questions.

- In universities, it is important to start with making facilities more friendly for use by students with disabilities. Spaces that are inaccessible will discourage people with disabilities to access them, not to mention cause emotional stress if they do.

- Having a disability does not give you expertise, and you don’t need to identify as a member of a group to be able to help them. You can be an ally without a disability.

The manifesto is a work in progress and we look forward to discussing our findings with UAL.

Keep updated with the project and our work on our website, email us at hello@onthemend.me and check out our Instagram and Twitter.

On the mend team:

- Rashmi Shankar - MA Media, Communications and Critical Practice, LCC

- Mathilda Della Torre – MA Graphic Communication Design, CSM

- Sophia Luu - MA Art and Science, CSM