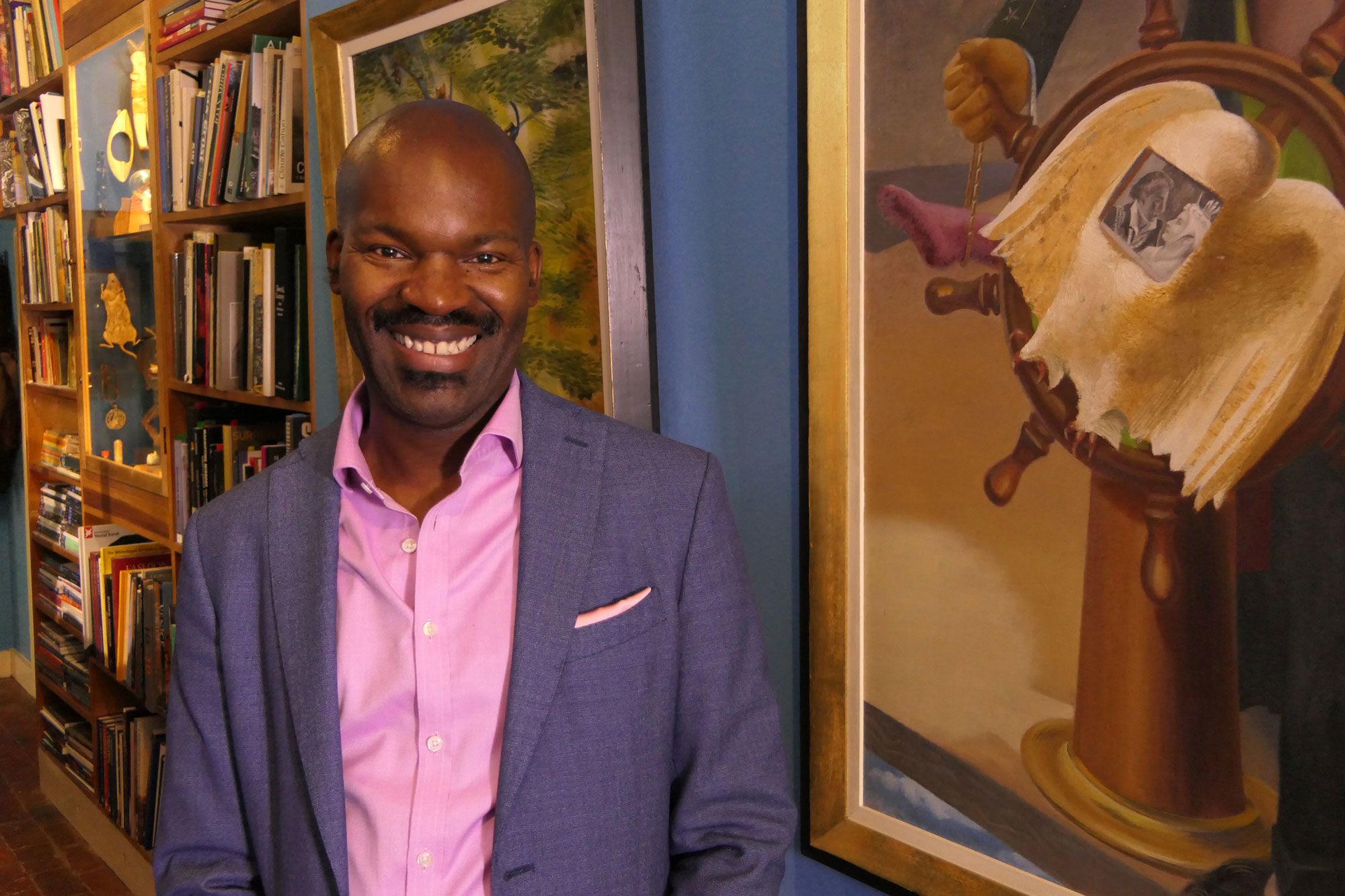

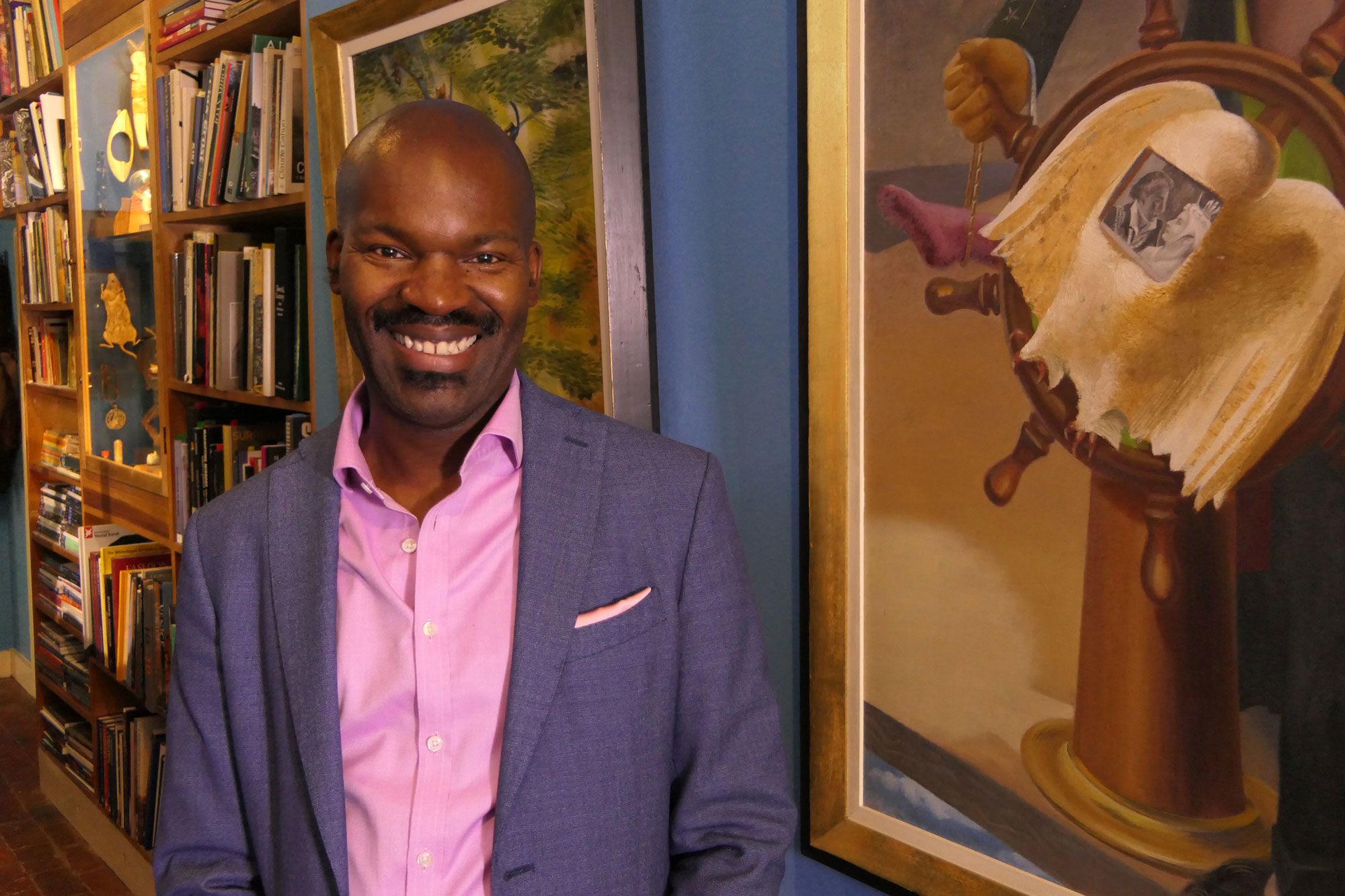

Black History Month: Meet David Dibosa, Course Leader at Chelsea

- Written byCat Cooper

- Published date 18 October 2022

, Chelsea College of Arts, UAL | Photograph: Alleycats TV

As part of our Black History Month celebration, we spoke to Dr David Dibosa - art historian, Reader in Museology and Course Leader of MA Curating and Collections at Chelsea College of Arts, UAL. David is a member of TrAIN and a Decolonising Arts Institute Associate.

Get to know David and hear what he loves about his work, what has changed and is changing for the better in the art world, and his hopes for putting ideas into action.

David, you wear many hats. Can you tell us a bit about your work and background - and what makes you enjoy working in the arts?

At the heart of what I do is a love for the arts in general and a passion for the visual arts in particular. I ended up working in and around galleries after training to be a curator but I'm sure I could have done something else related to the arts. Now I teach curating and undertake curatorial research. I write about curatorial issues and work as an Advisor to institutions like Tate and the Paul Mellon Centre, helping them think through developments in ongoing curatorial conversation worldwide. It's wonderful to see my energies being put to good use.

You have a portfolio of experience presenting and appearing on TV! Can you tell us about your media work and if you enjoy sharing your knowledge in this way? Do you have a favourite media appearance?

I've often said that 'art is not for everyone but it is for anyone who can find a connection with it'. Television, radio, alongside the range of digital media, are powerful ways of bringing art into peoples everyday lives. It's important for me to share a range of experiences, from the quiet moments of beauty that appear daily to the grand statements that we find from time to time in our national collections.

...being able to work in the media takes a certain set of skills. I am fortunate that I seem to have a knack for the combination of conviction and brevity that the professionals need. Everything in the media works at a different speed from academia where a volume of time is absolutely essential for what we do.

It's difficult to pick a favourite media appearance...each has demanded different skills...from the long reflective pieces to camera in the Darker Side of Black - a film directed by Sir Isaac Julien - to the quick-fire rounds in University Challenge with Jeremy Paxman giving me a withering stare.

You took over as Chair of the Whitechapel Gallery this year. Can you tell us a bit about this role and what it means for you and the community?

It is, of course, a tremendous honour to serve as the Chair of one of Britain's major art institutions. In its essence, being a Chair means being able to sit with something, to abide with an institution and its people. It takes patience, constancy and faith to just be there. Of course, there's a lot of work involved and a certain degree of resilience required. Just like with an everyday chair, anything can land in your lap.

It's Black History Month. Who are some of your inspirations from the Black community and why?

It won't surprise anyone to learn that I am inspired by artists like Sonia Boyce, Claudette Johnston and Zineb Sedira who time and again have demonstrated the stamina and commitment necessary to continually bring a fresh vision into the world. Curators like Gilane Tawadros also show me what principle and clarity can achieve. It's about caring for the wider spirit of a people, nurturing something that can grow.

This year’s theme is a bold ‘Time for Change: Action Not Words’. How would you like to see this being implemented?

Within the sphere in which I operate - I call it the 'art hive' - I'd like to see some more of the honey spread around. Things are changing. We're moving away from the 'winner takes all' approach of earlier times. There are more collectives now and much more of an emphasis on sharing and care for one another.

We need to continue in that spirit and do more to make it work in action. This means more bursaries, more scholarships, more prizes. The university needs to use its power and resources to allow more people to join in. Resources also need to help people remain in this environment with their mental and spiritual wellbeing intact.

I can't speak for the Black community but I can speak from the heart of a Black man who loves this world, this country and the wider arts community. Whether we see ourselves in that or outside of it, we each have so much to give. In my mind, everybody counts. The question is: how can our worth be made manifest for more to see? When Britain truly values what many people of colour have to offer we will become a wealthy nation, indeed. Since some Black people are still among the most disregarded people in our society - the refuse-collectors and the street-cleaners - by the time we recognise what they have to give, we will have recognised the riches that so many human beings have to share.

You were co-investigator on the landmark Black Artists and Modernism research project (2015-2018). Four years on, do you see an impact within UK collections and curation?

If you step across the road from where I am now in Chelsea College of Arts, you will see a work by British Guyanese artist Hew Locke. It's a mixed media installation called 'The Procession'. The artist has staged a carnival of mannequins and life-sized dolls, parading through the central Duveen Galleries at Tate Britain. As one critic said, it looks as if they are bringing a whirlwind sweeping through the gallery straight into the River Thames.

Alongside that work, there is a collections display called Sixty Years: The Unfinished Conversation, curated by Aicha Mehrez. It contains works by artists like Sonia Boyce, the UAL Professor who led the Black Artists and Modernism project on which I worked with people like UAL Professor susan pui san lok. I don't think our research made all these changes happen but we did make a contribution. Like all things of great impact, we were part of a wave.

Are you working on any current projects that you would like to share with the UAL community?

I published a piece on Rex Whistler, addressing the difficulties of displaying and seeing works that were once revered but have become embarrassing and even offensive. I'm working with a colleague from Goldsmiths, Dr Deirdre Osborne and I'm currently in discussions with our Archives and Special Collections Centre (ASCC) here at UAL.

The ASCC has an amazing team with people like Jacqueline Winston-Silk, Sarah Mahurter and Georgina Orgill. They are a treasure. They've been involved with projects with my students for many years. I'm hoping now that we'll find a way of moving from collaborative teaching to collaborative research.

You work with museums, galleries and collections on projects to review and improve their policies and collections. Can you tell us about a project that you have contributed to and some of the issues involved?

I was invited to work with an art institution in Rotterdam, which is now called the 'Kunstinstituut Melly' (Melly Art Institute). It was once known as the 'Witte de With' but got caught up in a controversy around its name, which belonged to a figure connected to historic human trafficking and the enslavement of peoples. The institution was being called upon to face up to its history and to demonstrate a break with the past.

It was a difficult time for the gallery and painful to see so many of its stakeholders either embattled, aggrieved or completely at a loss. As an art academic from the UK, I was able to bring a different perspective. Although I don't claim impartiality in any conflict, my point of view can be helpful.

So often I tell people that art is about taking a point of view then having the courage (and the skill) to share your vision. If you are able to find an audience now then you are fortunate. A university like ours has to be cherished because it offers the structures to support those whose audiences are yet to come. So many of us are fortunate to still be fired up by the creative arts. At its best, UAL holds a lantern to preserve the flame.