Narrative matters: how the stories we tell can change us

- Written byFrancesca Panetta

- Published date 01 March 2023

Stories are much more powerful than we usually give them credit for. Joan Didion drew no distinction between “stories” and “real life”. “We live entirely”, she wrote in 1979, “by the imposition of a narrative line” onto the “shifting phantasmagoria which is our actual experience.” Our understanding of the world, our view of ourselves, and our sense of what is possible are all stories we tell ourselves.

Throughout my twenty-year career as a radio producer, a journalist and most recently an immersive artist, I have been fascinated by the ways in which narratives shape our understanding of reality. At the BBC, the Guardian and MIT, I have pioneered new ways of telling stories as a way of challenging established worldviews. Corona Diaries was a participatory project using an open-source platform so the public could tell and share their stories about the Covid-19 pandemic. 6x9, an immersive experience of solitary confinement, was a virtual reality piece I co-directed for the Guardian about the psychological harm of isolation and sensory deprivation. By changing the stories we tell, and the mediums through which we tell them, I believe that we can bring about real-world change.

So when I joined UAL as director of the AKO Storytelling Institute last year, I was delighted to be joining an institution whose aim is to change the world through creative endeavour. A part of the university’s new Social Purpose Group, the Storytelling Institute researches evidence-based approaches to the theory and practice of purpose-led storytelling. Working across a wide range of narrative mediums and drawing on a diverse range of expertise, we are developing practical theories and methods for both storytellers and campaigners to put into practice both inside and outside the walls of the University.

This year we are launching our inaugural Storytelling Fellowship, which will bring together ten talented professionals and practitioners from across industries and disciplines to help us explore how storytelling can drive social change.

It’s an experiment, a kind of lab, to see what happens when campaigners and creatives come together.

On the one hand, the campaign world tightly focuses on their goals and how to achieve them. To guide messaging, they look for “insights” which reveal what target audiences think and feel about a subject. They think carefully about whether the narrative frames they are using will be successful: whether fear or hope will work best, for example; whether to represent a global issue in its entirety or to shrink it down to the local level.

When creative agencies are involved, they use this kind of research to create precisely messaged campaigns, which are carefully evaluated afterwards. Have behaviours changed? Was opinion swayed? Has policy been altered? The risk with this kind of painstakingly plotted campaign is that the public can often see it for what it is: advertising. And there is nothing less persuasive than the feeling you’re being sold to.

Art and media, on the other hand, have less narrow goals. There are countless artists around the world making socially engaged projects, from Ai Weiwei’s Sunflower Seeds (2008) to Pussy Riot’s “guerrilla gigs”. But most don’t have a “call to action” or an explicit ask, which makes it more difficult to establish the public or political impact. But this indirect and implicit approach can feel less of an assault on the audience. It’s not so obvious you’re being preached to, or told what to think. It may leave space for contemplation. The emotional imprint may stay longer, or allow new meanings to emerge.

So our experiment is to bring these two worlds together, to see what they can give to each other: what’s gobbled up and what is rejected. Each fellow will come with an idea for a project related to their cohort’s theme. Over nine months, with the support of the Institute and in collaboration with their peers, they will develop their research proposition, exploring narrative and creative approaches that push what real-world change they could have.

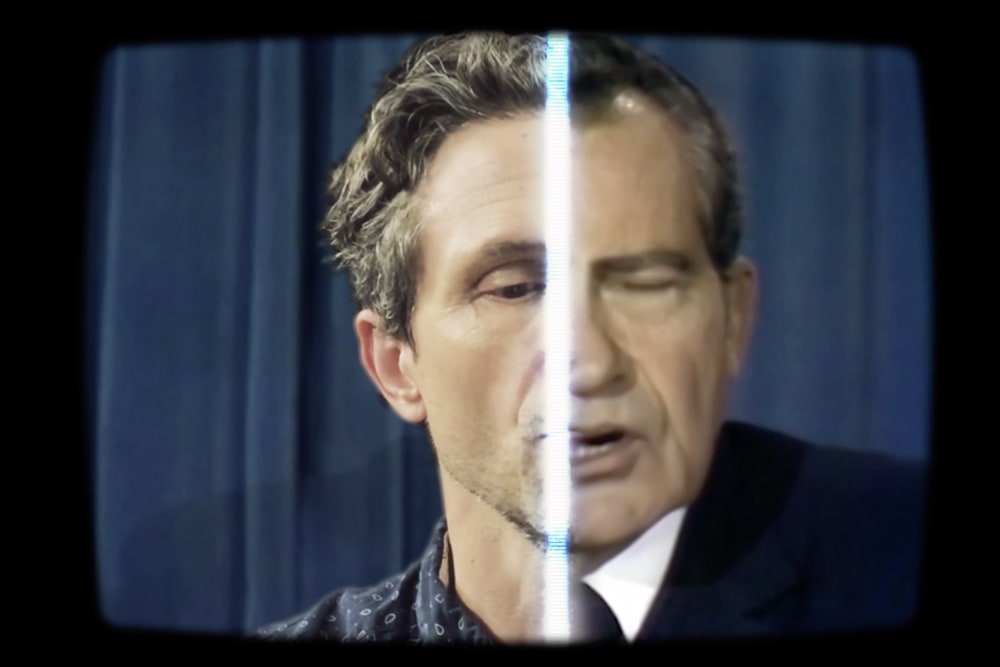

The theme for this year is Truth and Lies. Disinformation is a problem I began thinking about in 2019 as a creative director at MIT. There I co-directed a film called In Event of Moon Disaster with artist Halsey Burgund. It rewrote the history of the 1969 moon landing, taking a real script written by speechwriter Bill Safire for President Nixon to deliver in the event that Apollo 11 was unsuccessful. Using voice cloning software developed by the Ukrainian company Respeecher, we made a model of Richard Nixon’s voice to produce a voice clone. Using video dialogue replacement technology from Canny A. I. in Israel, we manipulated the footage of Nixon’s 1974 resignation announcement, so that his mouth moved along with Safire’s speech.

We conceived of In Event of Moon Disaster as a way of demonstrating the extent to which today’s technologies can bend reality. We hoped it would alert audiences to their own susceptibility, leaving them better equipped to question what they see and hear in the future. On paper, it seems we achieved that. The footage we produced is virtually indistinguishable from the real thing. In Event of Moon Disaster reached over a million people: the interactive website won an Emmy Award, and the 1960s-style installation has toured the world including DG Connect at the European Commission.

But those metrics still leave the fundamental questions unanswered. Did it enable people to navigate disinformation? Did we even reach the right people? Do those in power feel any more pressure to regulate? Did any of it make a difference? How would I even know that?

These are the questions that I look forward to investigating with the first cohort of fellows this year at the AKO Storytelling Institute. “Every crisis,” Rebecca Solnit wrote recently, “is in part a storytelling crisis.” The potential of stories to shape our realities has never been more apparent. “We are hemmed in by stories”, as Solnit put it, “that prevent us from seeing, or believing in, or acting on the possibilities of change.” If we are going to change the world for the better, we have first to imagine that change is possible. We can start by changing the stories we tell.

Francesca Panetta is the Director of the AKO Storytelling Institute.

Applications for the UAL Storytelling Fellowship are open until 15 May.