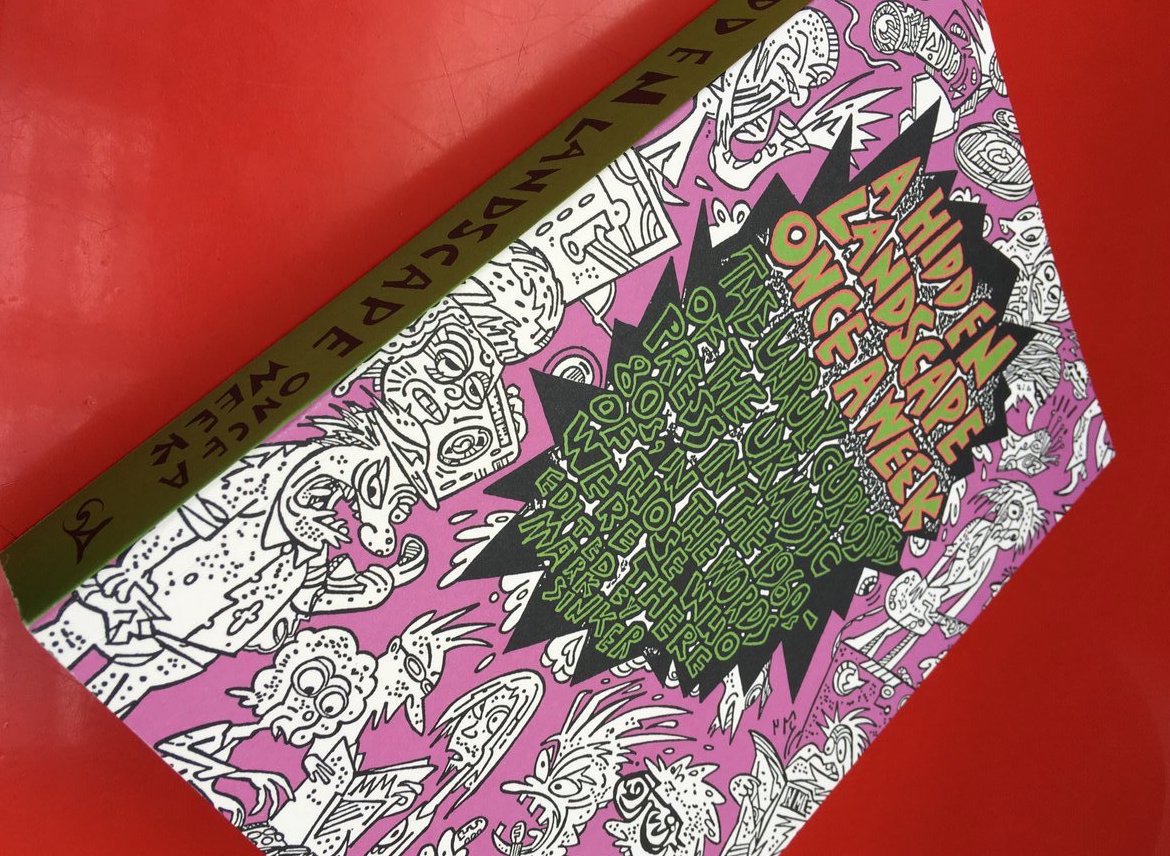

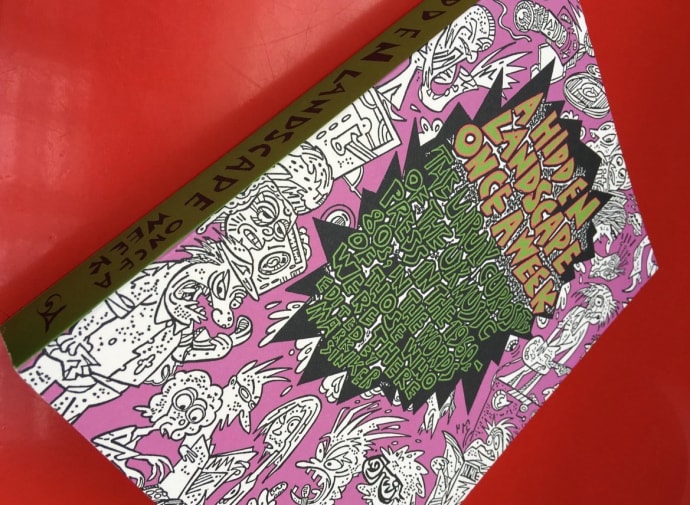

A Hidden Landscape once a Week: The Unruly Curiosity of the UK Music Press in the 1960s–80s, in the Words of Those Who Were There. By Mark Sinker (2018)

Reviewed by Kevin Quinn, PhD student at Central Saint Martins.

In May 2015, Mark Sinker, former New Musical Express (NME) scribe and ex-editor of The Wire, organized a two-day conference at Birkbeck University, London, entitled Underground/Overground: The Changing Politics of UK Music Writing 1968–1985. The event was an in-depth outlook at the origins of the British music press, with invited speakers drawn from those who were ‘there’. This subsequent book transcribes several of the attendees’ recollections, including pioneering jazz and blues photographer and writer, Val Wilmer, the ‘Runyonesque’ soul and reggae expert from East London, Penny Reel and Paul Gilroy, who still simmers with resentment at the ‘white boy battles from the bromantic ethnography of the NME office’. It also includes follow-up essays, ideas, thoughts and arguments on the power and potency of what was the seminal British music press.

From the well-known Melody Maker, New Musical Express and Sounds, to the UK underground press (International Times, Oz, Frendz) the book also places publications such as Disc and Music Echo, several magazines that emanated from the Beatles’ eruption and Time Out (itself a pioneering paper that addressed broader concerns such as race relations and police brutality) within this pantheon of publishing. Comprised of oral histories, interviews, personal testimonies, reflections, corrections, panel discussions and essays (Liz Naylor’s on Spare Rib’s relationship with punk being a good example) that (re)create an overview of a hallowed past, the book adds up to a bottling of the ‘fizz and bang’ that attracted almost a million readers a week in the 1970s. The plethora of writers both featured and talked about in this book arguably created the templates, the structures, the poses and the mythologies that persist today.

[…] for it is the function of the artist to make available for the rest of the community large areas of value and meaning. You can say that in a sense the emotion and value patterns of people’s lives are largely created by the artist, who find expression and form of words suitable for making known and interesting what was previously either unknown or uninteresting. (Huxley 1980: 10)

Telling tales of ‘ink-famy’, pretentiousness (contributor Paul Morley’s premediated provocations that both enriched and enraged, amused and bemused), socio-rockological analyses (Simon Frith’s placement of the hidden ‘we’ within the production of the press) and historiography, it is a whirling dervish story of culture that fed into, supped at and devoured the surrounding socio-political changes, championing and sabotaging artists. It went from infusing prose (textual and visual) with alternative and counter-cultural ideals in the early 1970s to gleefully irking purists and sacred cows by the end of that decade. In keeping with the progressive philosophies inherent in the music, the papers facilitated an irreverent reverence to pomposity allied to a zealous idiosyncratic pursuit of tastes.

The ‘landscape’ painted by Sinker is one perpetually driven and redrawn by a forward-thinking thrust, and the belief that music’s attendant properties were deserving of forensic scrutiny and elevation into higher forms of thinking about culture per se. Music and its mediation and transmission of meaning was a prism for the exploration of enlarged ways of thinking and being. Sinker opens the collection with an incisive, contextualizing essay arguing that this period under scrutiny witnessed unprecedented forms and styles of writing about music (writing as style and style as writing) and crucially frames these novel forms of music writing within the context of myriad forms of culture. The post-war sonic boom’s explosions of sounds, stars and (sub)cultures necessitated their articulation. As Sinker suggests, the reader was immersed in a welter of teenage obsession, confusion, ignorance and malice […] an unlikely cultural pocket developing largely unnoticed by the wider media, in which could be found valuable engagement with any number of off-mainstream projects: besides music, you might discover films, fashion, street theatre, science fiction, poetry and vanguard art, radical politics and cultural theory – and hints too on how to access the sexual or pharmaceutical netherworld. (3)

For many, the music press was a lifeline, an avenue, an escape tunnel and channel from/to other forms of identity: an entry into and membership of a club of like-minded others (e.g. Benedict Anderson’s theory of the ‘imagined community’). Which publication you bought and consumed was instrumental in the construction of self-identity and personal development. The reader was a key locus in the cultural circuit that existed between the organ, the writer and the text (written and/or visual).

Therefore, this book expertly illustrates what has been lost with the demise of print media (the period under re-inspection here implicitly suggests a ‘golden age’: the conference included discussions about the largely negative impact of the Internet on music writing). It demonstrates how the weekly rituals of anticipation and purchasing effected, encouraged and enacted debate and how a constant recoding of established norms, values and standards helped regenerate generations. There was an intimate rapport between the papers, the writers and the readers – an ‘ink-you-baiter’ – where the acquisition of knowledge took place in a slower, more private act of thinking at odds with the contemporary consumption of technonanism.

Evolution and renewal lay at the heart of the music press as it made demands on the artists and the readers and occasionally took authority and power to task without fear of censorship. Continued sales equalled authorial autonomy. This would change in the Thatcherite hyper-capitalist 1980s when the NME in particular would find itself in political disagreement with its owners IPC (especially putting Labour leader Neil Kinnock on its cover) culminating in walkouts and damage that the paper and the music press in general would never fully recover from. Commerce dictated content, resulting in discontent and signalling an end/beginning and vice versa. The overall feeling from the book, albeit beleagueredly, is that this revolutionary/evolutionary spirit can still exist in the written word: it is knowing where to find it.

At a launch for this book Sinker queried his own positon, arguing that he is first and foremost a journalist and not a historian. However, his raison d’etre was to ‘[…] look at trying to recover a sense of the future many hoped we were progressing towards’ (7). By compiling this collection he is using the past to rearticulate history and also using these (his)stories to (re)assert music and its writing as vital in pushing forward progress and striving for better conditions. The future has not turned out to be what it used to be. That said, this excellently collated book not only covers several histories of varied styles and novel forms of magical writing during times of what Sinker floridly terms ‘anxious gender politics, complacent entitlement and cultural parochialism’, but also shows the ‘early maps of achievements and the pitfalls of encounter as conflicted possibility, uncertainties of affinity in an argumentative dance with one another, crackle and distortion not as erasure, but as trauma’s response to complex mutual change’ (37).

Related Event: Subcultures and their mediated representations

Date: Thursday 31 October 2019

Time: 9am - 6pm

Location: London College of Fashion, 20 John Princes Street, London W1G 0BJ

Kevin, along with a group of UAL Post-Grad research students, in conjunction with Centre for Fashion Curation (CfFC) are hosting a one-day symposium titled Subcultures and mediated representations.

Topics will include how music fanzines documented and transmitted the acid house music scene, the Marquis de Sade’s influence on British punk, myth and membership of the Northern Soul scene, using black language and musical expression to explore the relationships between social and cultural ways of understanding identity formation through ideas of ‘high’, ‘low’ and ‘popular’ culture and Adam Ant’s performance personas, as dandy, highway man and Prince Charming as an entry point for discussion about military identities, masculinity and popular culture.