Archival cataloguing is, in theory, very like detective work. We start by going through an archival collection systematically, listing what there is as we go, but not moving anything or disturbing the way it’s filed. This is because a key principle of cataloguing is that archives should be arranged according to their ‘original order’; that is, the original order in which material was created and used. In reality, it can often be difficult to detect an original order, so sometimes we catalogue material according to what we think its original order would have been.

After listing all the material, we then decide on an arrangement – usually by trying to recreate the original order. We write descriptions of material – these have to conform to international cataloguing guidelines. And finally, we repackage the material to match the catalogue - everything gets a unique reference number, which is written on the box or folder housing it.

This is what happens in theory. In practice, cataloguing a collection is a constant process – it’s never finished. Sometimes, if you are adding something to an existing catalogue, and it’s obvious what the document is – for example a college yearbook - this can take only a few minutes to catalogue. But equally, it can be incredibly time-consuming – just understanding what something is can be difficult; for example, when cataloguing some newly-accessioned material in the Stanley Kubrick Archive, it took me nearly an hour to read through some early plot ideas which Kubrick came up with in the 1950s. I had to read through all of them to try to understand whether they were different versions of the same storyline or different stories altogether, what changes there were between copies, as well as trying to date them. All this whilst trying to read Kubrick’s famously difficult handwriting!

Follow us

Contact us

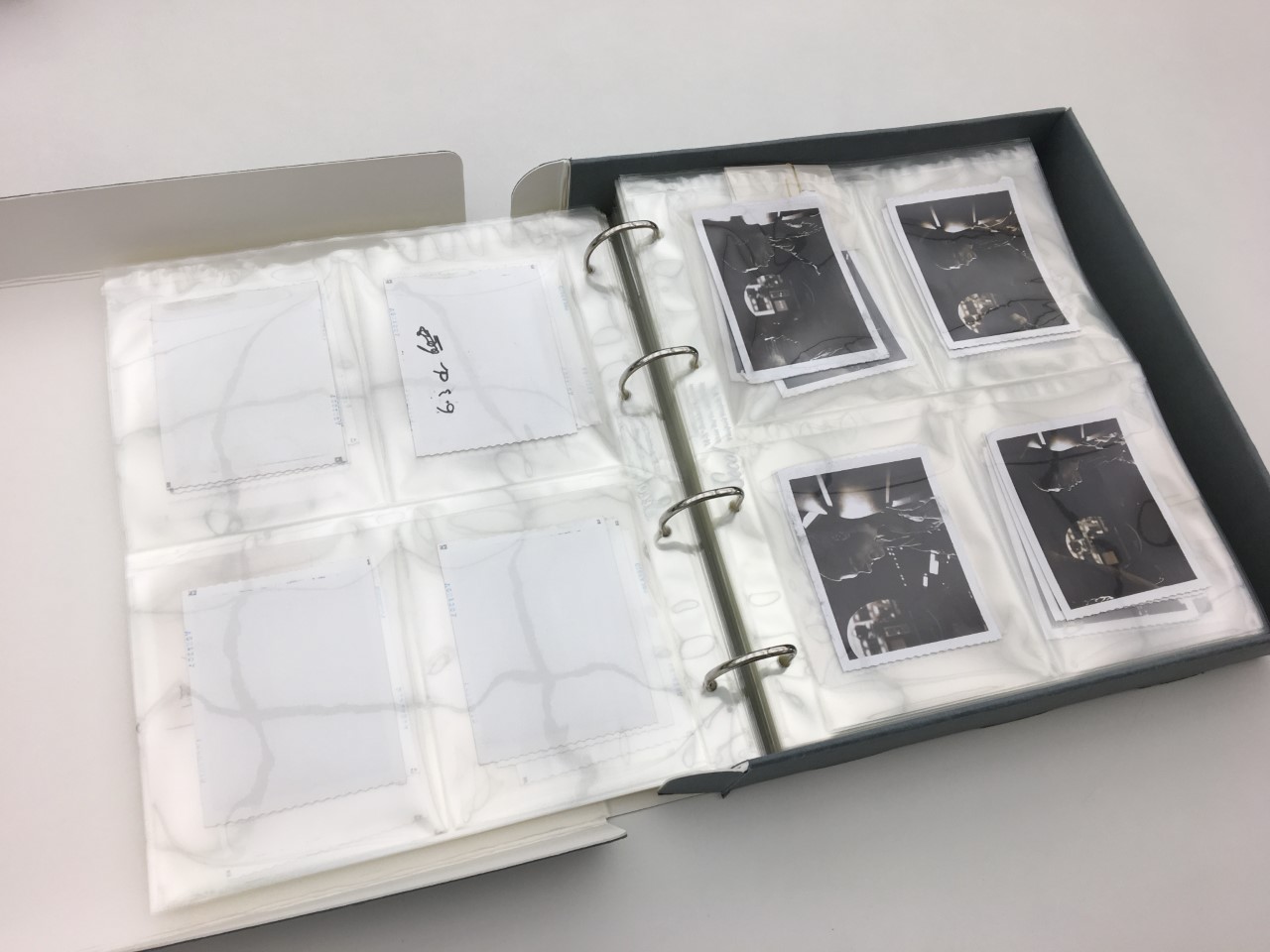

This is why often, our catalogues don’t have a description of every single item. Instead, we will catalogue a collection to series or file level, with one description covering a whole folder of letters for example, or a set of photographs which are all of the same place. This might be the case initially, so that we can catalogue a whole collection and make the catalogue available online more quickly for researchers to start using it. When we have more time, we might continue cataloguing in more detail. The Les Coleman Collection of underground and alternative comic books is a good example of this; it was initially catalogued to series level, and for several years, there was just one description covering two boxes of mini-comics. Researchers who wanted to see if a particular mini-comic was there had to look through two boxes containing hundreds of comics. Then one of our volunteers, Clara, worked on a project to catalogue these over the course of a couple of months, researching each mini-comic to provide contextual information and writing a detailed description of each one.

And finally, archivists don’t always get it right. Very few archivists will start a job as subject-specialists. Often, cataloguing is done as part of a project, but our job is to understand how to catalogue, not to be an expert on the topic. So cataloguing is a learning process – we research the person or institution whose collection we’re cataloguing, and try to learn as much as possible about them. But inevitably, mistakes occur. Sometimes an item or document might be wrongly identified, or its purpose misunderstood. In correcting these issues, researchers are often our main helpers. They are the subject specialists, and they often spend more time looking at the documents than the archivists! On several occasions, we’ve re-catalogued something or changed its description after consulting with one of our researchers.

Often, archive catalogues are seen as authoritative – they are what you look at to make sense of a collection, to request material, and to understand what something is. But catalogues are created by people, and they constantly evolve as more information comes to light or mistakes are identified. It’s important that we are open about the process of cataloguing, to enable people to understand both their benefits and limitations.

Keep in touch via our Twitter and Instagram, or email us directly: archive-enquiries@arts.ac.uk.