Sustainable voices without borders – Global Essay Series: Bo Mi Hwang, UPMOST

- Written byGiada Maestra

- Published date 16 February 2026

Introduction from Katie Kubrak, President of the UAL Alumni Sustainability Alumni Network:

“We are launching Sustainable Voices Without Borders, an article series dedicated to amplifying alumni stories that inspire and remind us how deeply interconnected our world is, as well as how individual choices can create collective change.

We are proud to share the first contribution from UAL alumna Bo Mi Hwang, who reflects on her personal and professional journey from studying textiles at Central Saint Martins to founding UPMOST, a circular design brand responding directly to South Korea’s plastic waste crisis.

Through this thoughtful think-piece, Bo Mi explores the intersection of education, material responsibility, and real-world challenges, demonstrating how sustainable practice must respond to social, cultural, and environmental realities.

Her story captures a core belief of our network and sets the tone for the series ahead: reflective, honest, and grounded in incremental progress. It reminds us that sustainability is not a single solution but rather an evolving practice shaped by context, collaboration, and responsibility. And wherever in the world that work takes place, its impact has the ability to travel beyond borders, inspiring others to act.

Stay curious with us, leave inspired.”

UPMOST

I am Bo Mi Hwang, founder of UPMOST and a 2018 graduate of Central Saint Martins (CSM) with a BA in Textiles. Before I began studying environmental issues at university, I was not someone who consciously thought much about the environment. However, the curriculum at CSM, together with the Green Week Project, naturally led me to become aware of environmental issues and encouraged me to question what kind of responsibility and perspective each of us can hold within our own fields.

What made this experience especially meaningful to me was that it did not feel like an attitude meant only for designers. I studied textiles, so I approached problems through design, but in doing so I realised that design is not simply about creating form. It is an act that requires the perspective and responsibility of a planner and a producer—someone who considers the beginning and the end of a problem, in other words, its entire life cycle. I also came to believe that this way of thinking is not limited to designers, but is open to people in all fields, allowing each of us to ask the same questions in our own ways.

For my graduation show, I transformed plastic bottles into strips and interwove them with textiles to build a three-dimensional structure. Through this work, I received awards in the field of sustainable design and was selected as one of 24 designers by the UK organisation TexSelect. These experiences taught me that plastic is not merely waste, but a material that can hold new possibilities depending on how we choose to see and use it.

However, the experiments and achievements I experienced at university led me to face a very different reality when I returned to Korea. During the COVID period, Korea experienced what became known as the “plastic bag crisis.” As food delivery increased rapidly, the amount of single-use plastic waste grew dramatically. At the same time, due to low oil prices, waste collection companies refused to collect plastic film and bags because it was no longer profitable. As a result, bags of uncollected plastic waste began to pile up outside people’s homes.

Korea is often known as a country with a strong recycling system, but witnessing the moment when that system failed made me realise that my work at university could not remain as artwork alone. I decided that it needed to expand into something that could function in reality. My business idea grew directly from the way of thinking I had developed during my time at UAL, and it began as an attempt to transform the problem of single-use plastic bags—one of the most visible issues in Korean society at the time—into a usable material. Through this experience, I came to believe that the real problem with plastic lies in its single-use culture. Plastic has many strengths—it is light, strong, and highly water-resistant—but because it does not decompose, it ultimately becomes a threat to the environment. That is why I set my goal to create a circular material system in which plastic can be reused continuously.

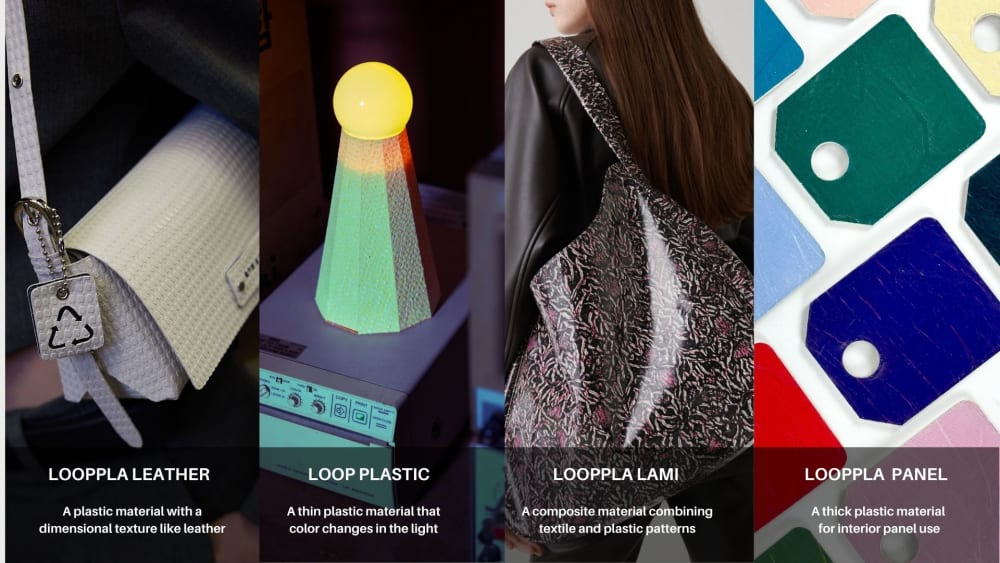

A major turning point in this research came from an unexpected accident. At university, whenever someone made a mistake during a project, people around them would often shout, “Happy Accident!” I am not sure if that culture still exists, but for us, it meant that an accident could also be an invention. While working with plastic, I once accidentally melted the material and created an unexpected pattern. That “mistake” later became the starting point of the plastic pattern-moulding technology my company now holds, which forms patterns directly through moulding rather than printing. This change in perspective became the driving force behind continuous research and development. Today, we hold patented technology that allows us to mould patterns as fine as 0.01 mm, making it possible to create floral, check, and leather-like textures from discarded plastic—patterns that, in conventional industries, were once only possible through ink printing or dyeing.

As this technology and its potential were recognised, we received investment from the Korean government and launched the brand UPMOST. We have worked to embed a sense of responsibility—designing the entire life cycle from planning and production to disposal—into our product design and production systems. As a result, our products are designed using a single material and are folded or assembled in ways that maximise recyclability. When a customer no longer uses a product or wants a new design, the material can be ground down into small particles and reused as raw material. In return, the customer receives a new product at a discounted price. This structure has become a continuous circular resource system in our business.

While running a sustainable business, I continue to encounter many forms of inequality alongside environmental issues. The cost and effort required to practise sustainability are far from light, and these conditions vary greatly between individuals, societies, and countries. For some, sustainability is one possible choice, while for others it is not yet even an option. Rather than trying to close this gap alone, we collaborate with people and industries across many different fields. Working with those who speak entirely different “languages”—such as fashion, interior design, and the automotive industry—has opened new perspectives for me every time. It has also reminded me that sustainability is not a single answer, but something we continue to build together.

This journey remains the most exciting place of learning in my life. And I hope my story can offer a small inspiration to alumni and students. I would also like to leave them with one question:

“Whatever field you are in, how do you practise sustainability?”